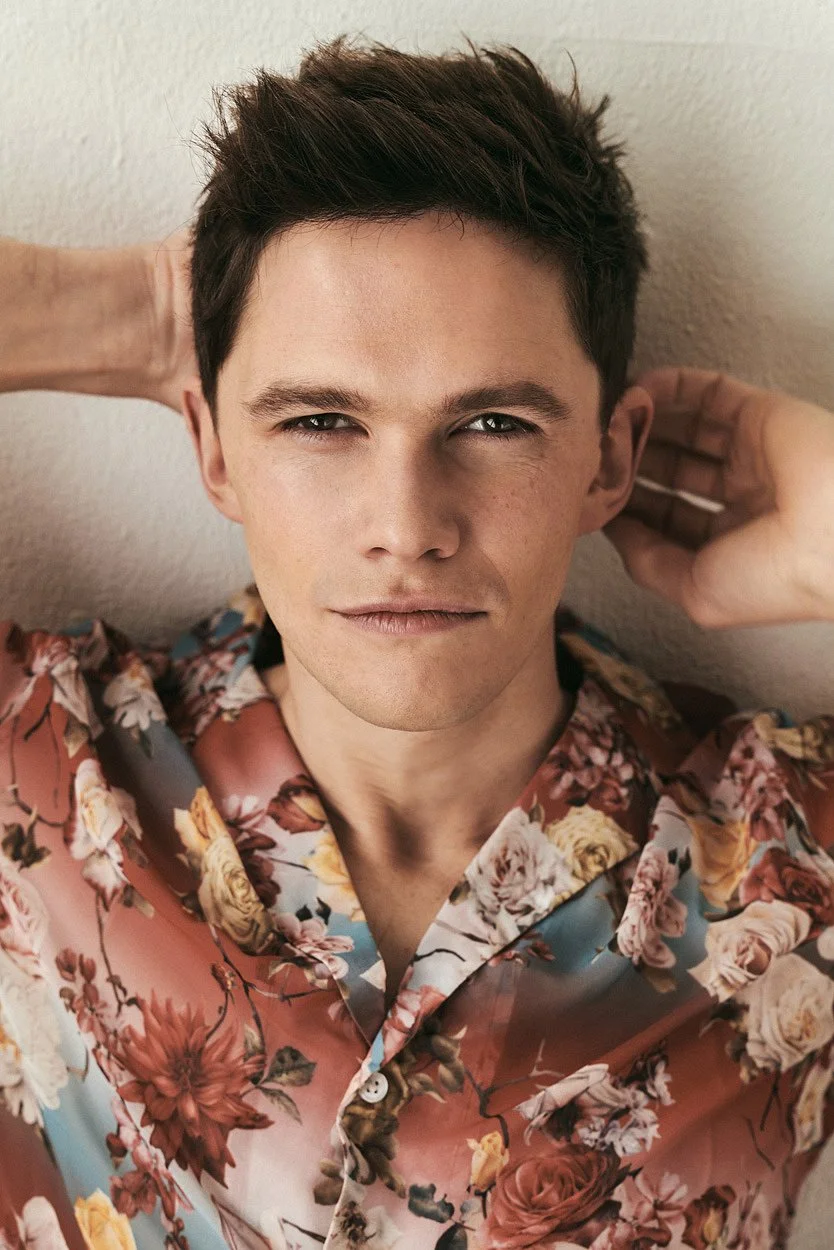

Tom Prior | 'Firebird' Celebrates the Transformative Feeling of Love

by Madeleine Schulz

Black thorns and roses, smiles and tears

They’re down together and grow so near.

is the poem that opens Firebird, Tom Prior and Peeter Rebane’s Cold War-era love story that depicts the concurrent debility and beauty of all-encompassing love. Set at an Estonian Air Force Base in the late seventies, the film is based on a true story about a love between a Russian solider and ace fighter pilot who navigate attraction, friendship, and loss under Communist rule—under which acting upon that attraction would result in severe punishment.

Though set in the late seventies, the film’s messaging still resonates fifty years onward—something Prior and Rebane sought to achieve. While the film inherently tackles a host of political issues wherein progress has severely lacked, it also drives home the story’s initial resonance: the importance of embracing, celebrating, and committing to love above all else.

Flaunt spoke with Prior ahead of the film’s theatrical release about the ways in which writing and acting a part influence one another, the weight of responsibility of doing justice to real peoples’ stories, and living a little more daringly.

Firebird first premiered at film festivals a year ago—how are you feeling about the theatrical release next month? Everyone’s finally going to see what you’ve created.

It was a pretty surreal time when we premiered at BFI Flare Festival almost exactly a year ago. Peeter and I were doing a virtual Q&A and we were actually in a theatre here [in Estonia], ready to watch the film, me, him, our cinematographer, and a couple other members of our team. The film didn’t work on the projector so we just ate cold pizza and sat in this theatre waiting for the rest of the audience in England to finish watching the film—all at home on their laptops—and then did an industry Q&A afterwards. And we’re like, well, did people enjoy the film or not? I mean, the feedback was good, but you can only really get what you hear from social media, and the few people on the industry panel afterwards.

When we took the film to Frameline in June last year it was kind of amazing to open at the Castro and be there in the middle of Pride weekend. It was just amazing to have that real live response. And then we’ve played at about fifty different festivals now. Maybe we’ve gone to about ten percent of those. It’s gonna be really cool to see how the wider public responds to the film.

You co-wrote and acted in the film, but signed on as an actor first. Did knowing you would play Sergey influence the way you wrote and edited the character?

I think I’d be lying if I said no! I wanted to remain as objective as possible. Meeting the real Sergey in Russia really helped inform my instincts and adjustments as well. For example, I was quite keen, even before meeting Sergey, that we shouldn’t really play him as this character who deals with shame or is sulky or snark—or focus on the self-struggle. Because we’ve seen that so many times. But also, it was his very sunny brightness and positivity that got him into the relationship and their perseverance of being together. That was really nice to find, that thankfully he wasn’t a horrendous, horrific person in real life, so we’d be like ‘oh god, let’s just make him into somebody nicer!’ He was this really, really lovely, warm, friendly, really generous guy. And was very courageous being himself in modern-day Russia. Peeter and I were at a restaurant with him in a suburb of Moscow and he was openly flirting with a male waiter. And we were like, what the hell? As in, he was very unfazed. That was really cool to see.

What was the weight, or responsibility, of playing a real person?

There’s definitely an added pressure. Some days I would give myself a hard time. We first met Sergey in 2016 and got to know him over several days. We took hours of interviews with him as well. He shared very deeply about the relationship and I wanted to ask him many questions about how the book differed from real life. I was like, where is the line between reality and fiction here? Because sometimes when you read the original story, it almost sounds like it’s too good to be true. And so we really went very deeply into that. And then we learned that he was really ill in 2017, he had to have some very intensive surgery. He passed away in intensive care afterwards. I felt very strongly that we should go to the funeral in Russia. So we asked some of his friends, and they all said of course, come. And we went to a wake outside the theatre which he set up and created in Oryol, and then we went to a very traditional Russian Orthodox funeral. I remember standing in this church with all this incense swinging around, and this very strong atmosphere, going, ‘I will do everything I can to tell your story with truth and with integrity and will do the best to honor how you would like to be remembered.’ So then that, to a degree, was a self-imposed commitment that I made. But yeah, it helped me also on those really tough days on set, where it was just like, I’m so tired and cold and wet. You know, emotionally wrung-out, just to keep on going.

I know Sergey asked that you focus on love, not politics. I think the film inherently does both, but could you tell me about the intentionality of the love aspect? As I think this comes across really beautifully in the film.

I am definitely aligned with Peeter in what Sergey told us. He was like, please make the film about love and not about politics. So we really took that element into everything we did, from the casting to how we finally edited the film, even with the creation of the music as well. One thing that’s really amazing actually, is Peeter and I worked really closely with Krzysztof [A. Janczak] who made an amazing musical score. I ended up becoming the musical supervisor on this film, totally by accident. Krzysztof did this phenomenal score, and when we were recording the music in Prague, in July 2020, kind of in the middle of the pandemic, I went out to the auditorium in the recording hall. I started listening and was like, ‘what is this? This is not one of the pieces of music from the film.’ It brought me to total tears and really emotionally wrung me out. I said to Krzysztof afterwards, what is that? And he was like, oh, you know, I wrote some extra pieces, maybe they go somewhere! And I was just like, it’s amazing.

This piece of music, I asked him afterwards, can you title this “If Roman Had Lived”? Because it’s through music, and it’s through film, that this story lives on. Their love lives on. It’s by putting a team together like that, who really follow that intentionality of creating it from a point of view of love, that we have reached such a strong end result. Even when it came to doing sex scenes, the intimate scenes, they were always character-driven. It was never really about creating a gratuitous love-making scene; it was more, let’s make it about love and how love behaves in this situation.

I saw you’d received some backlash to the film—like the screenings disrupted at Russian film festivals and social media attacks—could you speak briefly about how you deal with that?

When we were first accepted to the Moscow International Film Festival, I thought, wow. Peeter firstly was like, ‘I’ll eat my hat if we ever get accepted into this film festival.’ I was like, well yeah, it’s not really ever gonna happen. So when it was accepted, we thought, wow, maybe there’s actually real change going on there. We were genuinely like, this is really progressive and daring of the festival to do this. And then when it got all the backlash and the protesting and being invariably silenced at the festival it was very difficult. Apart from everything else it was just very sad, because there’s not a lot you can do when you’re silenced.

We weren’t officially banned. But then when the social media attacks come, nothing really quite prepares you for death threats, the abusive language on Instagram. Suddenly all these images and emojis, just like, eek. Nothing really prepares you for that. You just have to go, ok, this is an organized attack. And, you know, it’s from a belief system that some people still believe. There is still a community of people in Russia who believe that LGBTQIA+ people don’t exist, which is kind of astonishing. Being also that this is a true story. It was interesting, actually, Oleg [Zagorodnii] reached out to a few of these people who were doing attacks, going, do you realize this is actually a true story? It kind of quietened them down a bit. But yeah, nothing really can quite prepare you for that.

What do you hope people will take away from the film?

I hope that the film inspires people to live a little bit more daringly. From their heart. Seeing an example of people going all out, following their true feelings and following their heart and risking being authentic in themselves and the joy and the exhilaration that comes with that as well. There’s nothing quite like that feeling of being in love where you feel like you can do anything, and do anything to be together. I think that’s something so electric and it’s such a transformative feeling, when you feel like you can do anything. I think that that would really be my main wish that people take away: what love can do when you just go, I would do anything for this person. And I think that that really inspired me to live a little bit more courageously. And to acknowledge that that very behavior inspires other people to do the same.

What’s been your favorite response to the film thus far?

Somebody wrote to me and they said that watching Firebird was like receiving a big, warm hug. Kind of like an acknowledgement that it’s okay to be them. That’s been so impactful, when you make something and it’s literally helping people to feel like it’s okay to be little bit more like them. A little bit more like oneself. I remember seeing Call Me By Your Name at the London Film Festival premiere—I felt so electric coming out of that. Hungry to live a little bit more richly. I think that that’s something which has been really touching by so many people who’ve said, I’m gonna be a little bit more daring.

Another really amazing this has been, people have written saying, I’m not part of the LGBTQIA+ community, but I will give much greater respect now as a result of seeing the plight which people have to go through just to freely express who they love.

Could you talk a little about the poem at the start of the movie?

When we got down to one of the first edited assemblies of the film, we realized that we’d lost the poeticism which was in Sergey’s original story—which also was in the script. But just before, we’d taken a lot of advice from various people to save money and time, and we’d cut back a little bit on our poeticism which we wanted to keep in the film, which Sergey’s original story had. I think that’s probably the one thing that Peeter and I wish we’d kept a little bit more of in. A little bit more of these moments where Sergey is connected a little bit more to nature, and these moments where we’re a little bit more in his head.

But that poem came back during the post-production because it seemed to round off the film so well as an opening. The pain and the joy of love at the same time. It’s actually also the first lines of the original story. Sergey put different pieces of poetry, or different Shakespeare quotes, even, in different chapters in the book. This one is by a Russian poet and we wanted to put that back in because it rounded off so well, and has this nice topping and tailing with the smiles and tears which are right at the end of the film as well.

I’ll need to get my hands on a copy of the novel!

It’s very hard to find, but there has been quite a significant demand for people to read it. Although there’s really quite a few big differences as well.

That’s interesting—how did you decide where to diverge from the story in the book?

Most of it was about really putting in the political and sociological context of the time. When you read the original story, it’s almost surreal, you’re like, how on earth could this have happened? And there are some really beautiful moments which are between them and is this very poetic idealism of the story. If you made it literally as the book was told, people would’ve gone, this can’t have happened.

Probably the biggest change that we made was the character of Louisa. She was portrayed as, honestly, a formidable drunk in the original story. I think Sergey really blamed her for the way that everything turned out. But we really wanted to give Louisa as equal a voice at the end for how this was for her. In some ways, her tragedy is as strong as—if not more than—that of the two guys.

A couple of questions about you—when did you know you wanted to act?

That’s a really good question. It’s kind of been flipping in and out—sometimes I hate it, sometimes I love it! I guess I got quite a bug for it when I was about four or five. Just being on stage and being in a theatre environment. I always found it so magical going into a theatre which was nearby where I grew up. It was this atmosphere of potential, of magic or something. Going into a cinema was a similar thing. So I always kind of knew that there was something in it for me.

And I’ve just so fallen in love with the medium of film. There’s so much you can do, so much that can be done. It’s such a collaborative, creative expression. And I love what you can do with the camera and almost no words. There’s so much you can tell. It’s such a powerful way of telling stories. I really enjoy acting, but I’m very role-driven. I’ve got to get a good role which really works me up the right way.

What are your hopes for future projects—what types of roles will you seek out, do you plan to write more?

I’m definitely going to write some more and I definitely want to act some more. I really want to do much more representation of sexuality within films that are widening this particular genre as well. I’d love to see, dare I say, a more pansexual James Bond begin to emerge. That’s something I intend to create if it’s not already been created. Obviously, stepping away from the franchise, but that sort of character that would be spy- and espionage-based. Thriller stories.

I’m also fascinated by extra-sensory perception and human potential, epigenetics and quantum physics, and I really want to bring that into some films. I’ve got something which is in the process of being written which covers these subject matters.

Also things like—I mean, I was heartbroken when I found out Timothy Chalamet was doing a young Willy Wonka. We still don’t know much about that. But it’s always a part that I’d be so intrigued to play. There’s something about chocolate.

Firebird is set for theatrical release on April 29, 2022.

Photographed by Joseph Sinclair