Riotsville, U.S.A. | Cultural Illusion Takes Its Toll

by Shei Marcelline

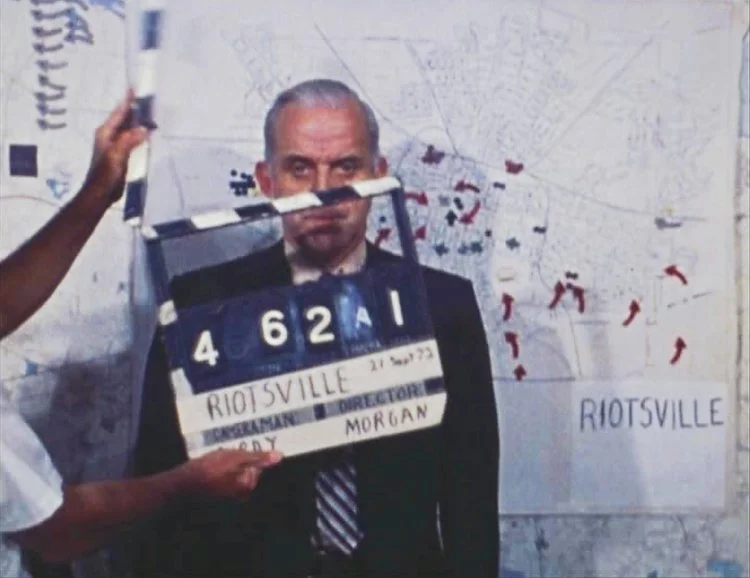

A scene from RIOTSVILLE, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

“Between two poles is a rather vast area we call reality.”

America sits quite comfortably on its throne of the unknown, allowing for ‘ignorance is bliss’ to permeate the air. We entrust our textbooks to accurately condense centuries worth of history, in the same manner we render government institutions trustworthy and politicians veracious. It isn’t until the socially and culturally repressed platform their voices that we realize history is told by the winners.

Riotsville, U.S.A. is an abolitionist essay film excavating and examining the overlooked militarization of U.S. police forces. Delving into the film’s conceptual absurdity, director and archival researcher Sierra Pettengill alongside writer Tobi Haslett center their convictions around 1960’s footage depicting law enforcement training for civil unrest. Riotsville proved to be a fitting name for simulated towns built on army bases intended to simulate rioting—a ‘precaution’ taken by the U.S. government following a series of protests prompted by racial injustice.

The film divulges into the aftermath of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Kerner Commission, a commission that ultimately funneled money into social welfare programs resulting in a 300 million dollar increase in police funding between 1964 and 1970 alone. The Commission’s intent to prevent America from regressing further into a “system of apartheid,” leads Riotsville, U.S.A. viewers to draw their own conclusions surrounding the present day consequences of militarizing the police.

Riostville was a ‘chessboard’ simulating game strategy. It was treated as a series of win-lose role play. Haslett shares, “If you live in a corrupt enough society, the very notion of citizenship is actually tantamount to being a spectator or an audience member. [The State] wants to make sure that our experience, in the USA, leaves us happy that we paid for the ticket.” Pettengill and Haslett acknowledge the power of constructing a narrative compiled of archival footage, however, they feel it important for viewers to engage with history in a manner that is open to interpretation. Riotsville, U.S.A. premieres in theaters today.

Check out the Flaunt exclusive interview with Pettengill and Haslett below.

A scene from RIOTSVILLE, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

How did you determine the subject of the film? Was it a topic you've always wanted to explore?

Pettengill: I am an archival researcher by profession. Most of my personal work is on the warped or fucked up narratives of America as told through the archives. I feel particularly fixated on or intrigued by right wing expressions of art or attempts to make faulty versions where you can see an attempt to envision a world. But I did not know anything about Riotsville, so I didn't know it existed until I read a little mention of it in a book by Rick Perlstein called Nixonland in 2014.

Its context is really interesting and something we really bore out in the film thematically. Perlstein was talking about the Hughes Commission, which was a panel convened after the Newark Riots to assess what happened, similar to the Kerner Commission that's in the film. [Perlstein] stated “the single continuously lawless element operating in the community is the police force itself” and then concluded the questions, whether we should resort to illusion or finally come to grips with reality. And then Pearlstein says the public was choosing illusion, and then he goes through extreme programs and policies and Riotsville was one of those. I find that framing actually just so clearly what we actually were doing in a way. This idea of choosing illusion rather than coming to grips with reality—The building, the militarization of the police, and the really accelerated and excessive building of the carceral state instead of coming to grip's reality is what I think you're watching be constructed in Riotsville.

A scene from RIOTSVILLE, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

I feel that's something cyclical in history—the public leniency towards illusion or the ‘ignorance is bliss’ train of thought. Is that a theme you contemplated when creating Riotsville, U.S.A.?

Pettengill: Yeah. It’s this idea of amnesia—cultural amnesia—in this country that feels really willful to me, that we're actively choosing to forget or wipe out very clear counter narratives. One of the ways we tackle that in this film is that everything—with the exception of military footage—was shot by broadcast television. The Kerner Report was a bestseller. So, this isn't a hidden narrative. It wasn't a covert program or anything. The fact that we've actively forgotten it is important to me.

Haslett: I think one of the things that the film implicitly tries to intervene on is the mechanism of forgetting, which is important for reproducing social conditions as they now stand. We see this in more contemporary examples, like the George Floyd uprising, which is now thought of as a kind of liberal ‘reckoning’ over racial relations in the United States, as if it were simply a series of very difficult, very public, very flamboyant conversations. But quite frankly, the George Floyd uprising, regardless of what you think about it, regardless of your political position, was an entire political and then reactionary sequence that was sparked by on-the-street confrontation and actual direct combat with the officers of law enforcement. It's astonishing to see how, in a matter of almost months, the most confrontational kernel of the George put up rising was overtaken by its manifestation as a certain kind of liberal anti-racist discourse. Race is more dangerous than that. [Sierra and I] share an understanding of how that transpired into the George Floyd uprising, and Riotsville is taking up many of the same questions. Even though there was a very public discourse surrounding urban uprisings and the actual implicit and explicit threat of these populations that were systematically disregarded.

A scene from RIOTSVILLE, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

How did you piece together a timeline for this film considering it’s primarily archival footage?

Pettengill: So, the answer to that question is that it took six years. The way I work is this very circular process where I have an idea, a conception, and usually a pretty firm political stance. And then when I find footage, like the Riotsville footage, I try to watch that and see what that archive is telling me in its own context and then let my preconception and experience of watching fight it out a little bit. Then as I gather material, I continue that process and reconsider what I've made or been making. It really was a long ongoing conversation between Tobi and Nels (editor) reckoning with footage, placing it, looking at what that did, what that does, how those images and sounds work together next to each other with writing that I just kept researching all the way through. The shape of the film informs the shape to come. It's a really iterative process.

Haslett: It's an essay film. The purpose of an essay film is similar to the purpose of an essay, which is to make an approximation or an argument. So in the architecture of the film, the priority was—how do we present the argument? How do we arrange the conceptual boards, such that this structure remains robust and compelling. As opposed to reconstructing something chronologically or trying to pull the viewer through this kind of lovely self-enclosed tube of narrative. We wanted to do something a bit more three dimensional and say, okay, here we have the riots, here we have the simulated riots and between those two things is an entire apparatus of image, making messages, capital reproduction that we need to touch upon so that the viewer can get a sense of the totality of the thing. But let's start at the most bizarre end of it, which is Riotsville.

Pettengill: There's something intangible about what you're watching or how to put that in language where it is different from a written essay—what images do when they're next to each other and how they reveal new things, or how you work to point someone's eye towards something that is not necessarily narrative driven. There's a series of layers. Something we talked about a bit was that I'm really resistant to historical storytelling where it's clear that the author knows what happened at the end and then builds a dramatic structure backwards.

Haslett: The two images at the end—they're not just competing ideas. They're competing diagrams. What we're trying to chart is the ways that reality muddled those diagrams, that both the utopian impulse and the rigid plotting of Riotsville represent these aerial pictures of an order that presumes stability.

A scene from RIOTSVILLE, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

What do you think the response is going to be in regards to using history, but creating an argument out of it?

Haslett: It's important to note that we're taking a risk in having collaborated on the film that we did in. On the one hand, we want to assert that history, even the history that's already happened is open to interpretation. But obviously, we think that our interpretation is the right one, right? That it's still a partisan in a sense. We want to be pluralistic enough, such that we insist these things can be reopened, but we also want to close them on the side of justice and close the question from the side of a very partisan left-wing position. On the one hand, we want to insist that history is ours for the retelling, but there is actually a truth that can be revealed through a rearrangement of historical material. So it's not just that we're trying to undercut the very concept of truth. It's that obscured underside or the fundamental dynamism of history as opposed to the presumably stable and immutable version of history, that is the official. That's what we're trying to uncover. Before we even started writing the script at all, Sierra and I were exchanging readings related to the explicit subject matter of the film, but also broader historical and theoretical readings.

Pettengill: Tobi and I are both really influenced by a lot of radical documentation in the sixties and beyond. The works of Chris Marker, we’re kind of working in that lineage, not that I would ever play such a mantle. Harun Farocki is another filmmaker who does it—that intangible interplay between an argued essay and gathering the visual information that is somewhere in an alchemical state and putting those together that are films that we talked about a lot. And that's the form we're drawing from.

A scene from RIOTSVILLE, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

What stood out to me was the way that Riotsville became a spectacle or a show. How has that perception resulted in consequences today?

Pettengill: My reaction in the last two years are—’all these people are so fucking stupid.’ Trump is really stupid. Everyone around him is stupid. No one knew how to cover that. It's like where are the deep ideological roots? It’s dumb. They're dumb. And that is the experience of watching this footage. That was something we wrestled with in making the film—how do you show the absurdism and the stupidity that we are laughing at as we watch it? Cause it is fucking stupid. It's not an accident. The callousness of the people in charge where they're just making jokes out of things is very indicative of how divorced they are from the violence of their actions.

Haslett: The particular intervention that a real urban disturbance or uprising actually makes in this world of spectacle. The reason that they need to turn it into a show and manage the dramaturgy of this simulation is because they know that the actual thing will be uncontrollable and will be widely publicized and will be a very different spectacle and a very different public picture. In a sense, the spectacularization of Riotsville deeply is related to the fact that people knew that every time a city went up in flames—because of an overt or just one of many egregious instances of injustice that take place every minute—one of them was just going a little bit too far. If you live in a corrupt enough society, the very notion of citizenship is actually tantamount to being a spectator or an audience member. [The State] wants to make sure that our experience, in the USA, leaves us happy that we paid for the ticket.

Any final thoughts?

Pettengill: We can talk in lots of abstraction, but a big thing a state does is allocate resources. The main inflection point of this film, which is the same one in this New Jersey Report, is The Kerner Commission saying we have to put billions of dollars into social welfare programs and then turning around and putting billions of dollars into policing. We can watch a moment when that split happens. In 1964, there was no federal money for police departments, and by 1970 there was 300 million, which I think is 2 billion by today's standards. That is a 3000% increase over six years. And then they're like, ‘we can't fund a social welfare state.’ It impresses upon me how subjective that is and what it actually means in regard to where money goes.

Sierra Pettengill, director of RIOTSVILLE, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.