Q&A | Russell Young

by Morgan Vickery

Russell Young is the British-American pop artist most known for his large-scale silkscreen paintings of cultural icons. After a brief love affair with photography, Young switched avenues and delved into the experimental series 'Combine Paintings.’ Soon after, an extension of his photography work, 'Pig Portraits’ served as both a glamorized and nitty-gritty view of celebrity culture.

Mesmerized by the drama of the American dream and visual richness of Lichtenstein and Warhol and Rauschenberg, Young paints the world in which he sees it; idealized. Looking to give his paintings a romanticized three-dimensional quality, Russell came across an old bag of diamond dust once used by the late Warhol, since becoming an iconic part of his work. More recently, Young exhibited the solo show, Superstar, at the Modern Art Museum in Shanghai. With 150 plus works, the show served as an interactive timeline of American history. While past portraits of David Bowie, Elvis, and Marylin, lined the walls with American culture, a new series titled ‘The West,’ diversified the mix with iconic western celebrities like Bruce Lee.

At the Brooklyn BRT Print Studio, we spoke with Russell to discuss the evolution of his career, creative process, silk-screen printing methods, favorite works, and much more:

From an early age, you were drawn to the idealized drama of the American dream. Having lived in the U.S. for some time now, what have you come to understand from this so-called “American Dream?”

Great question. It's like the movies really. The first time I came to America I was in Miami and I remember getting in a taxi and going to a cocktail bar on the beach, and everything looked richer, even the blue on the top of the taxi inside the window. And growing up in northern England with the absence of light, I loved it in Miami and especially California, which is where I now live, and I've lived most of my time. It's the light that excites me. I wake up every morning--I don't have curtains in my room--a light is pouring in the bedroom, and every morning I appreciate not having the rain. And it was the idealist thing; seeing Marilyn Monroe, films like the cowboy movies, it was always this aspirational thing. I go off driving on road trips on my own in the desert, and I sometimes pinch myself that I live in America. It’s just the whole paraphernalia and the entire landscape; just the open space. You can't believe that there's all this open space and sky, it still amazes me after 25 years.

I have two studios in California, and I have this old aircraft hanger that has no running water, and this crappy little toilet outside, so you only go there to work. I go down there and to the beach quite a lot. I surf, but I swim out into the ocean as well, quite far and just float. But when you're standing on the edge of the ocean or cliffs, it's so similar to the desert. I get the same feeling that you’re in this empty, yet vast space. There's so much richness, and there's so much in there, but you have to find it and look for it.

After famous photographs and video films, you evolved towards painting. What evoked this switch?

I fell out of love with that industry, and it fell out of love with me. I felt that I needed a change. Ever since I was three years old, I'd done these beautiful abstract trees and just making marks and enjoying myself, and I felt it was time to do that. It took me about a month of being away in Italy to make that decision, but the second I made it, I knew it was the right decision--I knew it was the last thing I was going to do in my life, so I knew it was forever.

When did your love for pop art and culture begin?

I guess it was through Lichtenstein and Warhol and Rauschenberg. I love the colors. I would see reproductions in books where I saw those artists first, and then I would go to galleries or museums and see their work. I couldn't believe there was so much pigment, so much richness, so much color. It was the color rather than the subject matter that appealed to me first of all.

What creative blocks do you experience?

It’s strange, but a year ago I came here [New York] to work, and everybody was on their phones, and it was interrupting the creative flow, so we all put our phones away and for two weeks worked without phones. I stopped then looking at the news, so I don't know what's happened in the world for the last year. I mean I really don't know what's happened in the world. It struck me that my phone was the biggest disruption, even though I don't have any computers or take my phone into the studio, I was still going out to check my messages and then it would come in the studio because I would play music off it. And then I’d just look at an email or look at something, or I get a text from somebody, and I answer that. Sometimes it's as simple as looking at the time, so my concentration was being constantly interrupted.

So three weeks ago, I left the phone away, told the few people that need to know where I am in an emergency where I was and how quickly they could get hold of me. And what happens is you get bored, and nowadays when we get bored, you look at your phone, right? You check your Instagram; you check whatever, you text somebody a message, you Snapchat, whatever. And it interrupts that creative process. And that creative process ultimately comes from the boredom, and out of boredom usually, excellent things come. The word I've used for it is deep concentration. And I now realize that in maybe ten years I haven't really had much of that deep concentration.

On every full moon, I go on a hike. Sometimes I'll go up into the mountains above me, which go up to 4,000 feet and there are lions and bears up there, but I stay safe. I'm up towards Ventura and Santa Barbara, and it's just fascinating. One night in the full moon I walked 16 miles from where I live up the coast and swam around coves and walked, and I started to get back in touch. These last two rainstorms we had, I went and slept under the freeway near the ocean. There are quite a few homeless people that seem to do this trek up the coast, and when I go surfing sometimes, I sit there and talk to them. I was talking to this one guy about where he'd slept the night before, and he told me this magic place on the freeway that's right on the ocean. So I went there, and it's this beautiful place, so sometimes I just go sit there.

Explain the symbolism behind “Pig Portraits.”

They were a reaction to my former career. I would make people look better than they actually were through my lens; and make them look cooler, meaner, hotter, more beautiful, handsome, whatever it was. And so the “Pig Portraits” came from this booking clerk or policemen that took these pictures in a second. I thought, “Okay, they're going to look gritty and stripped down and bare.” But by the nature of the way I see and the way I execute things, I sort of glamorize them beyond... the Sid Vicious--he looks so beautiful and young, and Elvis looked wonderful. I glamorize them more than I intended to and then that's when I realized, okay, okay, this is how I see the world, which is fine.

The use of diamond dust has become iconic in your work, when and how did you discover it?

It was an old bag of Warhol’s diamond dust. I was looking to give my paintings a three-dimensional quality to it and a reflective quality; we had tried inks, and we tried all these different things, and then we suddenly discovered this old bag. I used to work on Warhol’s old [printing] press, and we put [the diamond dust] onto the painting, and it took this fantastic life on it. I took it back to California and pinned it on the wall of my house, and the moonlight hit it at night, and it reflected. And then I took two or three of the paintings outside and just hung them on the bushes, and I was like, ‘Oh my God, I love this stuff.’ It makes it tactile. Art, by the nature of it and museums, you're not allowed to touch, and I think most of my work, whether I'm printing on felt or whatever surface I'm printing on, you can touch. It has this dreamland, almost sculptural element to it that you want to touch and as you move around it, it glitters, it shines, and it catches the light. Depending on where the painting’s hung, it looks different, and at different times of day, it looks an entirely different way. I did a black on black diamond dust painting, which was stunning and at one angle, all you see is diamond dust--it's like a block of diamond dust. At another angle the image comes; It’s really versatile.

How did you get your hands on Warhol’s screens?

Luther [Davis] bought part of this old shopper for another screen. We also have inks that we still use that are Warhol’s own and this bag of diamond dust. It’s a little nod to him.

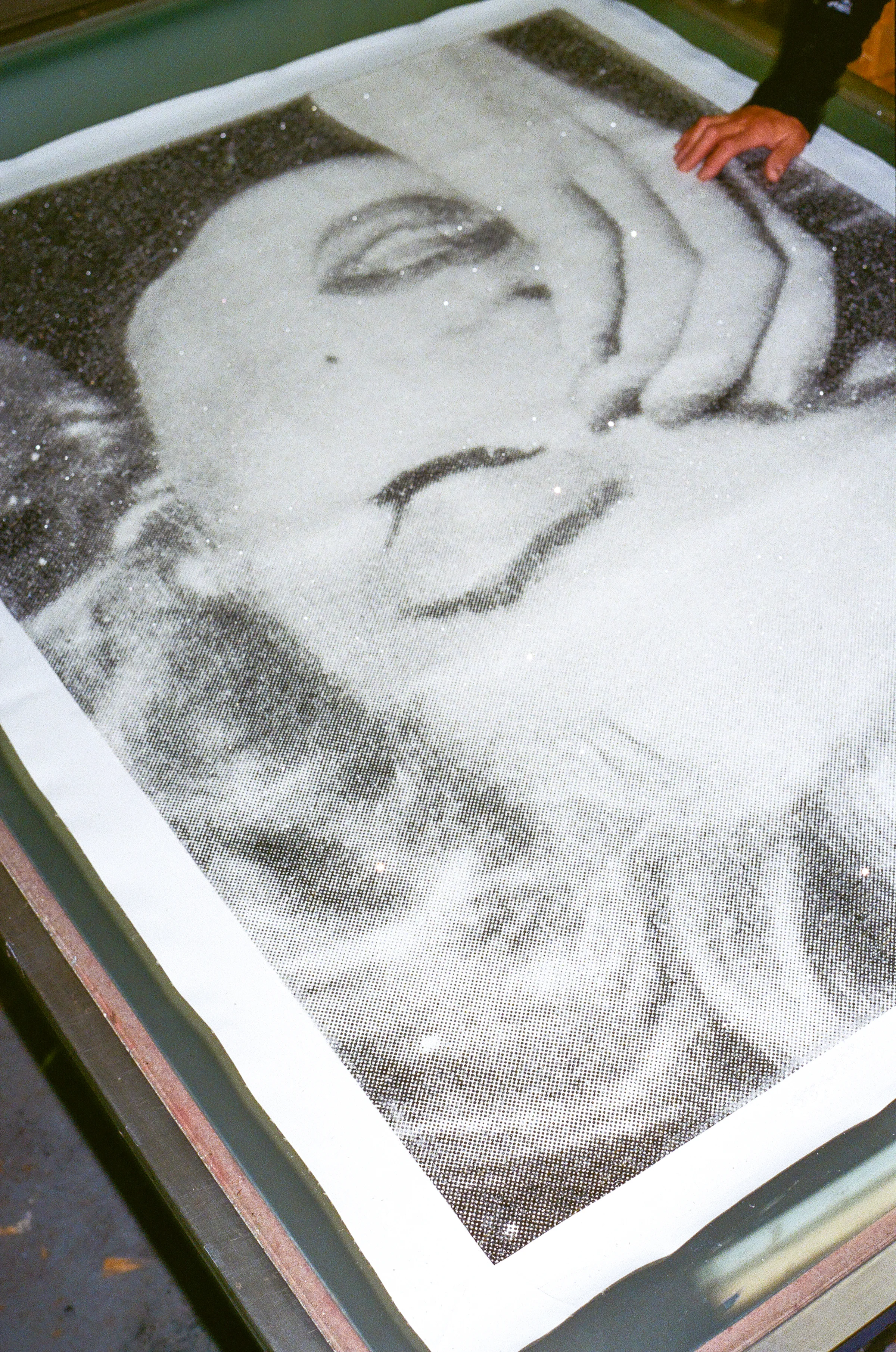

Russell and Luther in the silk-screen printing process.

What can you tell us about your silk-screen printing process?

Oh, it's a really simple process. It's the same thing they did for signs years ago, and how people print T-shirts--that's what's beautiful about it. It's a photograph, and it’s exposed, it’s a negative, it goes onto a screen and then we’re pushing it through. Most of the time, two people will be on the side literally pushing the ink through. But sometimes on the biggest screens, there's six of us around the screen actually pushing down and pushing the ink through. So it's quite masculine--it's quite a raw process when we're working on these large scales. But I love the simplicity of it, and it's magic as the thing comes out. It still has magic for me. It’s instantaneous. People ask me sometimes, ‘How long does it take?’ and it either takes five minutes or 50 years.

From what I know, the difficulty comes from burning the screen correctly and perfecting its outcome.

Yes, getting the right amount of detail; you want the right dot screen size, and multiple layers go in. When I came in the first day with Luther, we had a very similar language because he works with all these different artists every year, so he has a very sophisticated understanding of light and dark and shadows and contrast. I came from 15 years as a photographer, so I came in with that experience, as well. I wasn't an artist who just did abstract paintings and then tried to, you know...we started on quite a nice understanding and level.

And how long have you and Luther worked together at his BRT print shop?

18 years. I mean, he's one of my best friends. I've had more lunches with Luther than any other being on the planet.

What project has held the most significance to you thus far?

It would be a series called Helter Skelter. I have a website which is called bankrobber.co, and I've just opened it up as an online shop, which I've never done before. I'm putting stuff on there that is rare, and unusual, from my archive. Some of its 15-20 years old. And some of it is a little bit more recent, but on there are some releases of the Helter Skelter bookings and Helter Skelter prints. One thing I've done on newsprint, which is stunning and a beautiful little print--I took the image of the Hells Angels beating Meredith Hunter to death at the Rolling Stones ultimate concert in 1969. You see the pool cues, you see the Hells Angels logo, but within the crowd, you can see somebody is wearing a Mickey Mouse tee shirt.

On the larger paintings, which are 16 feet by 10 feet, it's taken me a month to do them. I go into this one screen that’s maybe 15 inches by 22 inches, and I use enamel, which is really thick and gloopy and is oil-based, and I print that time and time again, and I really go into this crazy frenzy--it’s sort of like a trance-like dance. And I'm playing music very loud, normally Joy Division when I was doing those. I use music a lot in the studio, and so I lose myself in it, and the paint drips in with me. But then it starts to lose its sense of an image to me even after the first screen. Once I’ve done one screen, then the screen itself becomes an implement just to put paint down on a surface in the traditional making that goes back ten thousand years. I’m just using something to make a mark, and then I go into it and maybe do it for an hour. And I do that eight or nine times over a month; I let it dry, and then there's another layer, and the end is almost like a Hieronymus Bosch painting that has everything upside down, and I don’t know which way it’s oriented. And then you see the streaks coming in from the edge where the painting has been; it’s very feral, it’s a very wild gesture, and I feel feral when I'm doing it. There's this wonderful nonchalance, and I almost forget myself and what I'm doing. It’s almost like this crazy dance or trance-like situation.

And that series came out after being really sick in 2010; I ended up in a coma and almost died. I mean, almost died a couple of times for eight days. I got the swine flu. I got ADRs, and I was not meant to live, and I came out of that not being able to walk or breathe. My memory is still compromised strangely. I used to have a photographic memory, and that's gone, but different photographic memories come back. I forgot the color green; I didn't know if my father was dead or alive--I couldn't remember that — a whole lot of stuff. I had to learn to breathe, and I couldn't read or write. I had to learn all these things again, and I started with these smaller screens and then that built up and up and up. I used to surf and then I started to surf in bigger and bigger waves. As I was doing these bigger and bigger surfing waves, it was way beyond my skill set. But it was that feeling of being next to nature and this fierceness. It was part of the recovery, really, doing those paintings. And they're absolutely amongst my favorites. They’re screen prints, but it's not like any screen printing ever done before; they very much look abstract. So it's that balance of composition and the way things are electric and alive, and you have to find that balance, as well.

Tell us about your most recent solo show, Superstar, at the Modern Art Museum in Shanghai.

Well, it was a great opportunity. A gallery represents me in China, and the UK called the Halcyon Gallery, and they gave me the opportunity to show through their contacts. And it was quite amazing to see, I mean, there were maybe 150 paintings, something like that. There was this photo booth that we set up where people could take selfies, and then they went through this timeline of 60s American history; it was an old coal depot turned into an art gallery, and there were Marilyn and Elvis and all these beautiful things. You know, soundtracks of Martin Luther King Jr. and Hendrix. And then by the time we got upstairs, like 10 minutes later, your selfie was on the wall in a lightbox, but it looked exactly like one of my colorful mugshots. There was grain on it and photocopy stuff that I sometimes use on the mugshots as a sort of in between the image and the final screen print. So there's a whole wall of 10 portraits of different people, and then at the end, you see David Bowie, Sid Vicious, Elvis, my mugshot; which worked well. So that was the introduction to it.

I was able to show my new series called The West, which I hadn't shown anywhere before. I’ve probably shown 15 paintings from that series, but the [Superstar] series was 200 paintings deep. Then I created a new series of iconic western people—they were just people that I really loved. Bruce Lee was in there, and then I worked with four or five different Chinese celebrities that I'd seen in movies or had some meaning to me.

It was great to see all my work in one place; I'd never seen that. I mean, I know my work, and I can remember it all, but it was great to see everything as an entire collection and really understand sort of the thoughts in my head about the American dream and fame shame. I had one series years ago called Fame Shame, so that's what I deal with. I deal with fame, but then I deal with the darker side of fame. The mugshots encapsulate that perfectly. I'm always asking people, “Am I showing them this stupendous view of the American Dream or am I showing them the souring?” And you know, how the American Dream has gone wrong. If you take historical context really, you had Woodstock and the summer of love and then right after that, you had its Altamont, and that to me was the turning point--the souring, the end of the idealism and the souring of the American Dream.

Photography by: Phoenix Johnson