Nobody out There Likes You

by Members of the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility's Writing Workshop

Nobody out There Likes You

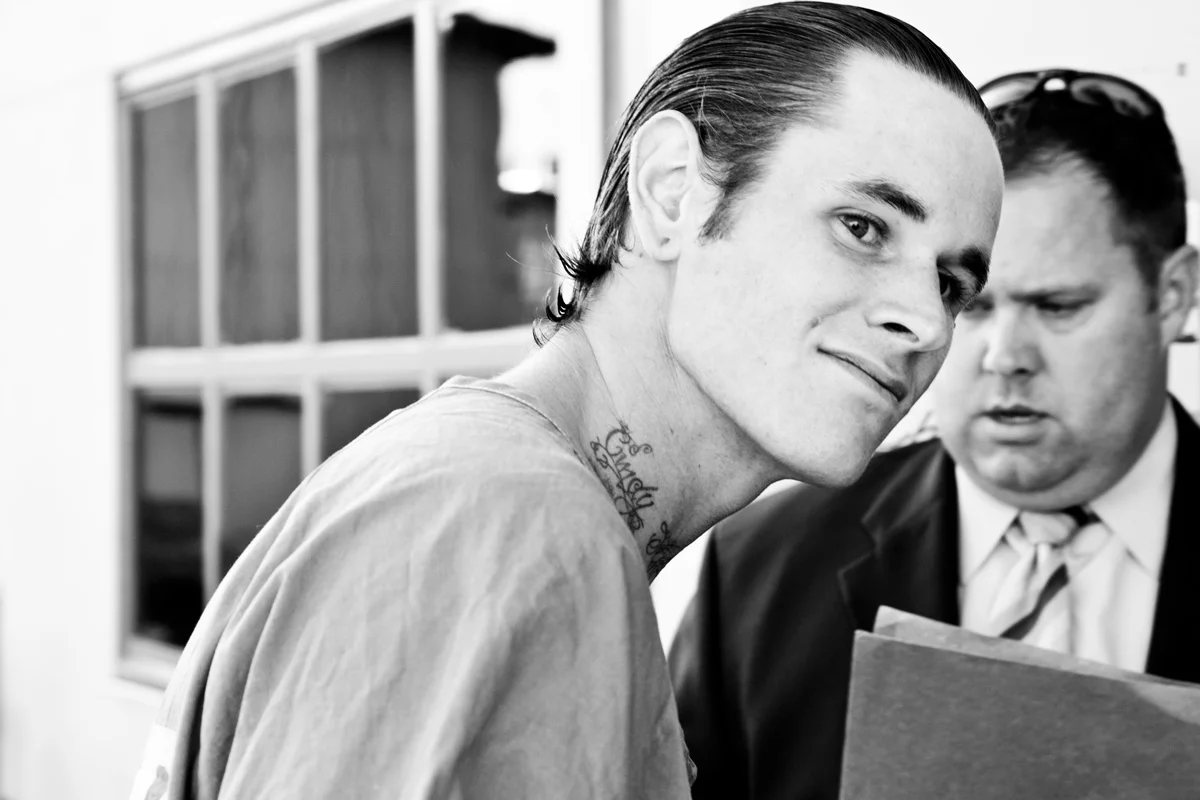

Scenes From a Writing Workshop Within a California Prison

Editor’s note:

When we’re checked in at security at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility, Lt. Logan and Dr. Sutton explain to us that in the event of a hostage situation, they do not negotiate. A woman wearing rubber gloves scans us with a wand and then gives us passes which we clip to our shirts.

RJD, a sprawling state facility, about a mile from the Mexico border is, like most California prisons, overcrowded, violent, racially segregated and terrifying. We cross the lot. The sky, suspended between the black top and a further distance, is sharp, as if its blue were volume, rising to a shriek, and the white buildings snap against it like bones drying in the heat. We stop to take a picture. Across from us is the yard. Like small blue brush strokes behind multiple rows of chain-link topped with curling concertina wire, inmates stand dazed, governed by an impossible boredom.

There is something unsettling in the indolence imposed on the men by their confinement, likewise in the subtle variations in the way each man wears his “California blues.” We take particular note of the different kinds of footwear. It’s strangely compelling, the differing cuts of sneakers. These are level four inmates—apparently the most dangerous.

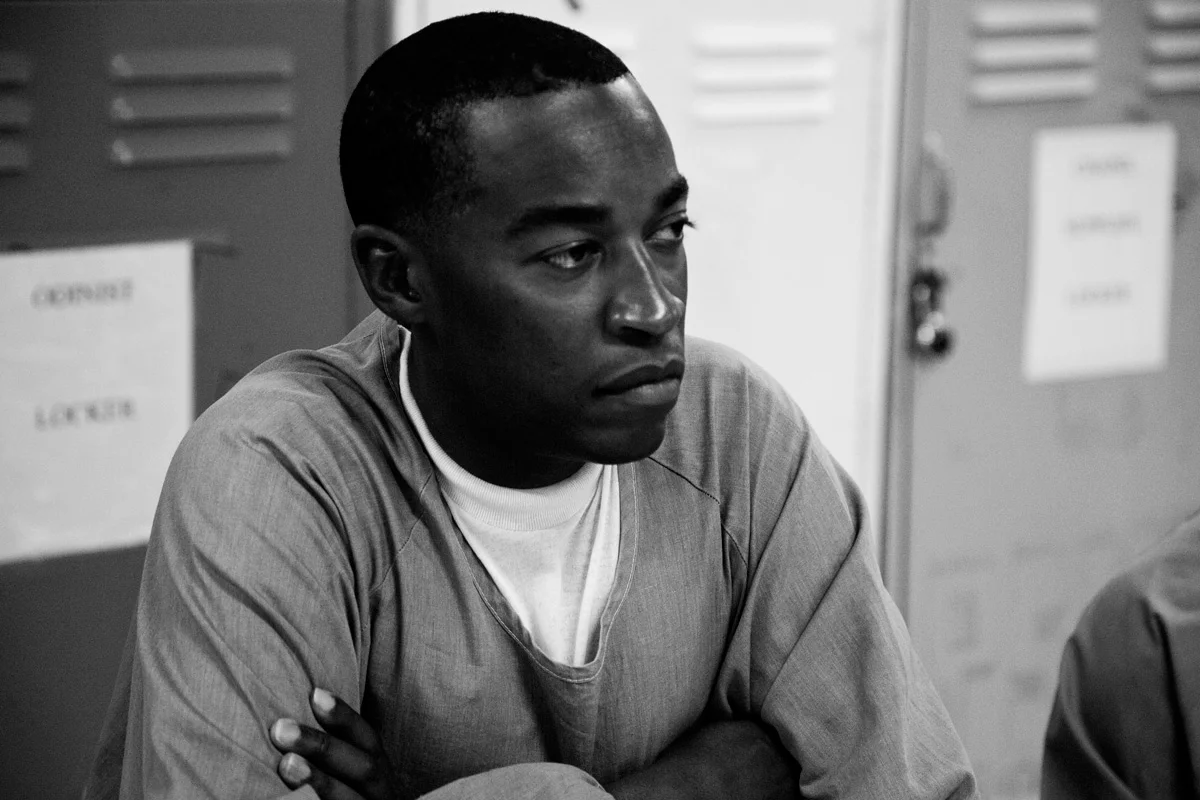

The actual reading takes place in the prison chapel, just across from the yard. Inside, every faith is represented. We help the men who are granted access to set up the tables and chairs, and this enables engagement. The few questions we want to ask, we don’t. We take in the cages of books, the faded posters on the wall, the small stage before which is placed the lectern, where the men will stand in turn to read that week’s assignment. It seems all they have.

We just sort of listen to them talk. This isn’t because we’re frightened but because we are around men who have done something with their lives and live their lives at such a pitch it’s nearly unfathomable. It’s like watching someone wake up only to realize you’ve been the one asleep. In fact, most of these men have more or less woken up in this workshop, because of this workshop, and this is their holy ground. It’s as though we’ve discovered something private—this place where they learned to fashion themselves, to turn prose into a mode of hearing.

The meeting begins with the Serenity Prayer.

Dr. Paul Sutton is a professor of Criminal Justice at San Diego State University. He was our point of contact to get inside the Richard J. Donovan Facility. Lt. Patrick Logan, who works at the facility, and the warden, Daniel Paramo, were likewise instrumental in facilitating our entry.

What follows then is a speech given to the men at the beginning of the workshop, read by Dr. Sutton. Mixed throughout the speech, in italics, are excerpts from some of the inmate’s writing assignments. I want to thank Lt. Logan, Dr. Sutton, his wife—who makes all of this possible—and the men in that room, for having the courage to be listened to and to listen themselves. Thank you.

That night, as I lay in bed, the words echoed in my head. “You’re just not smart enough! You’re just not smart enough!” I was angry, but not at my teacher or even at the other kids, but at myself. “Why was I so dumb? Why did I always fail? What was wrong with me?”

—Joe A. “Smart Enough”

I stood there, uncertain, against the backdrop of more than 40 years of study—a decades-old dissertation on sentencing reform; scores of papers, books, articles, and op-ed pieces on crime and punishment; more than 30 years of taking college students on weeklong excursions through the American correctional system; three feature prison documentaries, a career of studying men and women doing time.

What was wrong with me? Others fit in so well but I had to struggle to make the grade. They had the best toys, listened to the right music, wore the current fashion, said the right thing, and knew the right people. It all seemed so easy for them. They were cool: I wasn’t.

—Patrick A. “No Shame in That”

Yet, there I stood—unsure about this new undertaking. I had never done anything like it; neither had any of the 25 strangers, mostly lifers—in for murder—who surrounded me in that non-descript room of forgotten grey—a prison chapel set aside for us for 4 hours a week, for the next 15 weeks.

We were going to write.

Seeing the brutal truth of my reflection makes me cringe. The 23-year-old scar that traces my jaw line recalls a childish BB-gun fight. A mole on my nose, appearing shortly after my birth, conjures each taunt or cruel remark from schoolboys otherwise forgotten. The divot above my left eye marks the impact of raging right hook of a drunken stepfather. The pockmarks above my cheek denote a teenage bout with chicken pox. The freckles that dot my face still whisper my mother’s comforting words, “They’re called ‘angel kisses,’ baby.”

—Brian L. “This Damned Mirror Shows No Mercy”

Prison writing is a centuries-old genre. Incarceration was the setting or inspiration for a host of literary classics penned by professional writers—e.g., Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World, the writings of Marquis de Sade, and Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol. External examination of penal systems by learned critics and authors e.g., Alexis de Tocqueville (Democracy in America) and Michel Foucault (Discipline and Punish)—has supplemented these first-hand accounts.

“There’s a really nice man, a good man, that lives down the street; his name is Jerry Jacobson. He just got married and he’s going to have a baby boy very soon. I want you to help this family out. I want you to get to know these people, help them in any way you can. Mow his lawn, wash his car, fetch his groceries, and don’t ask anything in return. Can you do that?”

He answers, “Yeah. I can do that, but why?” I ask him.

“Because you’re a good kid, that’s why.”

I turn and walk down the hill; I do not have the heart to tell him that in 20 years, he will be sent to prison for life for killing Mr. Jacobson.

—Eric O. “10-Year-Old Self”

More recently, as academic scholars populated prison literature with their largely external critiques of the prison world, a new discipline within sociology emerged. The literature of so-called convict criminology draws upon the studied observations of inmates who have received a graduate or doctoral degree, usually a Ph.D. The aim was to offer the public informed, well-reasoned “inside” accounts of incarceration, otherwise available only from professionals who likely never set foot inside a prison or who, in any case, could not speak credibly from the perspective of those who had. Besides providing a forum for “degree-d” inmates, convict criminology has whetted the public curiosity for—and legitimized, to an extent—the writings of inmates, generally.

Twenty years in prison inches me forward in my seat, as I plant my face in palms grown atop elbows that seem rooted in my knees; “deservedness” ricochets between my ears and slows to swirl upon my tongue. In a hushed whisper, the word drops. My eyes follow, watching the word I dare not say turn red as it splashes off my tennies, as shotgun pellets are flung violently across the body’s bright, white shirt.

—Patrick A. “The Body”

But the standard is high. The public is demanding, generally intolerant, and their attention span for this sort of thing is short. To succeed, the work must be done well.

As we began, it was critical that these men understand that.

“Nobody out there likes you,” I began.

You’ve all been a boon to strengthening my soul. Whether you encouraged, shared, or just listened, it has all been a blessing.

—Cesar L. “What About Wednesday”

“In fact, they hate you. They hate what you’ve done; they hate the pain you’ve caused. They don’t care about you or what happens to you.”

And the finished product of my mom’s portrait was nothing less than that. She loved it. This was not a matter of pride; it was a matter of beauty.

—Kyle R. “Drawing Mom”

I felt the room tighten. “But you know that. Just look around you,” I added.

A smattering of nods and reluctant shrugs.

“But that’s not us. That’s not what we think. That’s not what we believe. We don’t know you and you don’t know us; but we’ve met plenty of men and women like you behind those hundreds of thousands of faces we have come to know in our travels behind bars.”

I find myself alone, again, in the small, cold church. I sense death all around me, feel its hot dampness, smell its putrid dankness. Older now, I am still paralyzed by that familiar terror that keeps me from the coffin. I know it’ll be her in the casket once again.

—Tyrone H. “Another Funeral”

“We know there is plenty of good in you. You have stories and you have lives. What you don’t have is a platform from which to tell your stories and a vehicle to carry those stories forward.”

Back to reality, back to my misery. I hate my parents, I hate society, I hate myself. Yet death has spared me once more.

—Gerardo L. “Death”

“We’re going to try something different here. We’re going to try to help you to find your voice, to sharpen it, and to muster the courage and confidence to tell your story to the millions of people out there who have given up on you.”

“We believe you are worth the effort; we believe you are entirely capable of doing what we are talking about; and we firmly believe that once society hears your voice, they will see in you the humanity they had thought you abandoned. We ask you for two things—honesty and respect. Be honest in your writing and respect your reader. If you do this well, those people out there will change their opinion of you; and, eventually, prison will change.”

Seeded by monsoons of an ancient wound, stone barriers crumble, loosing the mighty Yellow River upon my cheek; the great Yangtze upon his. The two distant rivers converge, flooding.

—Jojo D. “The Yellow River”

Aware that contemporary prison writing often amounts to little more than inmate complaints about food, crowding, filth, and violence, we would ask these men to do more, to dig deeper, to develop and reveal insights about themselves—critical discoveries about who and why they are and where they are headed.

“No one cares how bad things are in here; in fact, most will applaud what you decry. So, spare us your grievances: it’s a waste of time, and it’s not what we’re about.”

I wore pea green Philadelphia Eagles pajamas, a Pittsburgh Steelers beanie, and owned a slightly banged-up Dukes of Hazzard lunch pail with a mismatched Scooby Doo thermos that I’d scored for a quarter. No, there’s no shame in that.

—Patrick A. “No Shame in That”

We would ask them to write about insecurity, fear, family, friendship, love, hate, happiness, hope, despair, redemption, death and mortality, heady stuff, to be sure. We would not ask them to write directly about their crimes or their lives in prison, although references would prove inevitable.

That was the challenge—to have men who had failed both at life and at crime to succeed at this; to be honest in a world that rewards lies and deceit; to make themselves emotionally vulnerable in a place where vulnerability is weakness and weakness is death. As one inmate confessed to me much later in the semester, “I’ve spent my life fighting—being beaten up, stabbed, and shot. But standing at that podium, facing these guys, to read my work?

In disbelief, my brother asked him if he knew who I was. As if offended by the question, he insisted, “Claro pendejo, that’s my son, Jose.”

—Joe A. “Love”

As I stood amidst this skeptical group of mostly high-school dropouts who could not distinguish a subject from a predicate or identify a single part of speech, of hardened criminals whose principle means of expression was a seasoned fist, a well-turned shank, or an exploding handgun, all seemed ready to embrace the challenge.

27 ½ years, give or take a few seconds, minutes, hours, or days. This lifer, serving a first-degree murder sentence, is found suitable for release, no longer a risk to society. With a snap, God’s mercy and compassion has lifted the greatest burden from my shoulders.

—Bernie F. “Counting Time”

“Let’s see what we can do,” I ventured. And we went to work.