Benedict Cumberbatch

by John-Paul Pryor

Wool and cashmere coat by BottegaVeneta, button-up Shirt by Sandro, long-sleeve cotton top and leather shoes by Jil sander, and trousers by Salvatore Ferragamo.

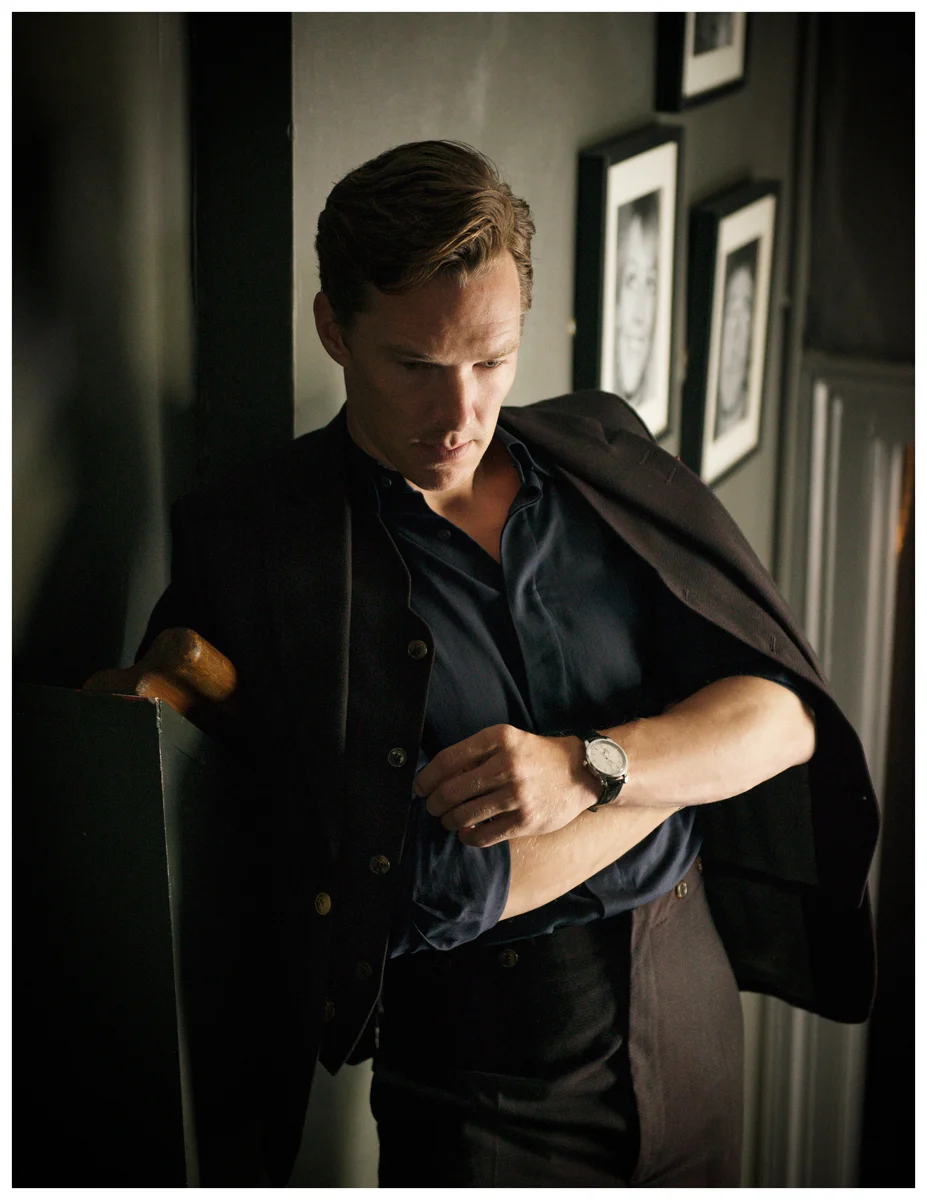

Wool jacket and trousers by Vivienne Westwood MAN, button-up shirt by Berluti, and watch talent’s own.

Coat and button-up shirt by Alexander Mcqueen, trousers by Allsaints, and shoes by JilSander.

Shearling jacket by Allsaints, cashmere henley by BottegaVeneta, and trousers by Carven Homme.

Wool and cotton striped coat with zipper detail, natural cotton shirt, wool and cotton striped trousers, and cowhide shoes by Comme des Garçons Homme Plus.

Wool and cashmere coat, lightweight cashmere patch pocket artist’s shirt, and cashmere mesh tank top by Burberry Prorsum, cashmere trousers by Berluti, and twist calf monk strap shoes by Alexander Mcqueen.

Wool and cotton striped coat with zipper detail, natural cotton shirt, wool and cotton striped trousers, and cowhide shoes by Comme des Garçons Homme Plus.

Benedict Cumberbatch

One Must Imagine Somebody Happy

Albert Camus posited in his existential treatise

The Myth of Sisyphus

that there is only one great philosophical problem, and that is the question of suicide, the accelerated process of non-being that has consumed the lives of many a great man and woman in the canon of history, including Cambridge alumni WWII Enigma code-cracker Alan Turing, a man whose mathematical genius saved millions of lives by helping to bring the Second World War to an early conclusion. Given

carte blanche

by Winston Churchill to lead a team of some of the greatest minds of his generation in a race against the clock to solve the greatest puzzle of his age, the British mathematician was later arrested for his homosexuality and suffered enforced hormone treatment at the hands of the very establishment he had fundamentally helped to save, and as such, the most important period of his life—an official secret for over 50 years, and now the subject of the major Hollywood film

The Imitation Game

—is a tale of tragedy and pathos of classical magnitude. “It makes me very angry that the establishment actually then deigned to posthumously apologize or forgive him,” says the Harrow-educated classically trained British actor and self-professed “straight ally” Benedict Cumberbatch, who takes on the role of Turing in Norwegian director Morten Tyldum’s stunningly executed Weinstein-funded biopic. “I mean the word ‘forgiveness’? The only person who ought to be using the word forgiveness is Alan Turing [Turing was granted a “royal pardon” for his sexual persuasion in 2013]. His

behavior

didn’t need pardoning.”

Suffice to say, Cumberbatch is in a serious mood when I meet him on an unusually hot summer’s day in a leafy suburb of Hampstead in North London, and what strikes me immediately about him is a slight otherness and intensity; an intangible quality that suggests a racing mind. He’s polite as hell, of course, and likeable, but he’s also in a hurry, as his Flaunt shoot is very soon to become another across town. Thusly we are both plunged into a semiotic race of our own as we drive through congested London traffic, seeking inspiration between words and pauses in the sporadic summer showers. “It was a hysterical era, of course,” he continues. “It was our version of McCarthyism; based on the red threat. They persecuted a man who, yes, went to a liberal college in Cambridge, where he probably forged more liberal views than most, but he didn’t actually think he was special—he just never apologized for his nature. The punishment was either two years of prison or chemical castration through weekly estrogen injections and he chose the latter simply because he wanted to carry on his work. Incredibly, even the change in his body made him look at the idea of cellular distortions and adaptions through various environmental influences. Everything he did in his work was influenced by his life.”

The importance of Turing’s work cannot be underestimated: He spent the duration of World War II trying to crack the Enigma code with his team of mathematicians, chess champions, and cryptographers at Bletchley Park, creating a groundbreaking machine that could figure any determinable function given the correct set of instructions. This is what later mathematicians would come to describe as the Turing Machine, which laid the Euclidean foundation stone of the ubiquitous modern-day computer. Turing’s mind and vision would shape history irreversibly—and yet he was not interested in the political spectrum of the war per se. Like so many great analytical minds his love of mathematics was driven by a desire to crack far more metaphysical problems. In fact, as a young man he was consumed with the notion that the human mind, or an energy of sorts, could live on after corporeal death. This belief was born from his passionate, unrequited love for his only friend at boarding school, Christopher Morcom. “The one thing I could relate to, really strongly, was Turing’s humanity,” says Cumberbatch as we swing around a corner narrowly missing another car (“Two Jaguars nearly kissed then,” he quips). “He fell in love with this boy at school, and that was a love that was forbidden. Christopher died tragically of bovine tuberculosis, and Alan set that as his benchmark and everything he did from that point on was to make this first love proud. He came around to the logical conclusion that a spirit will live on basically by others trying to honor it—it’s terribly moving.”

The key to the brilliance of The Imitation Game is precisely the lonely, emotional, and searing inner journey made by Turing, whose difficult choices are brought to life with the aid of a sterling supporting cast, including Keira Knightley as the fastidiously supportive code-breaker Joan Clarke, and Matthew Goode as the brooding chess champion charmer Hugh Alexander. However, there is really only one performance upon which this movie hinges, and it’s a performance that is world-beating in its thoroughly convincing attention to detail. Alan Turing may be an icon in the history of mankind’s achievements thus far, but in the more modest world of “lights, camera, action” Cumberbatch’s own star has risen exponentially in the last five years, and he is arguably the perfect candidate to play just such a social outsider and reluctant rebel. After all, he is almost as famous in the U.K. for his sharp-tongued intelligence and outspoken stance against the Iraq War in the early-noughties as he is for his Emmy-sweeping take on Albion’s ultimate sleuth, Sherlock Holmes. He too is a product of the at-one-time-famously-sadistic boarding school education system at the heart of the British establishment—having graduated from the hallowed halls of Harrow Boys.

“I think Alan was very much in tune with notions of spirituality,” says the actor on finding the crux of his dramatic quarry (himself a self-professed Buddhist, having spent a year in his college days teaching at a monastery in Tibet). “I think Alan’s fascination with what was possible with artificial intelligence is something that is really inspiring. I don’t think he set out on an ego trip to destroy God, or any kind of monotheistic religion, but actually to just celebrate what the human is capable of, and he set about the study of creating something beyond the human… There is a beauty in that. I mean, we can formulate and explain things in scientific terms but it doesn’t take any of the magic away; revealing the work, or the mechanism behind the beauty doesn’t destroy the beauty. I imagine that anyone who has a spiritual commitment and yet is a practitioner of high logic through science or mathematics can say that truth is beauty—the mystery of beauty is still truth, but to them it could be a spiritual truth or a factual truth; the two are equally divine.”

It’s unsurprising to hear Cumberbatch make reference to the British romantic poet John Keats, given his famous love for poetry, which he is regularly called upon to recite at literary festivals the world over. And yet, despite any such satisfaction Turing may have taken in his work and the friendship bestowed upon him by his at first begrudgingly, loyal group of comrades-in-secrecy at Bletchley Park, Turing was clearly struggling internally with Camus’ postulation that the two most important choices one has in life are whether to believe in hope or self-destruct in the face of existence’s ultimate reductio ad absurdum. “I do see what you’re saying about the polarity, the argument to be or not to be, the idea of ending the absurdity,” says Cumberbatch, his responses always measured, considered. “I think, for everyone, the real shock of suicide is that you do get that feeling of helplessness. It’s an isolated state of mind, and that’s the problem with it. It’s kind of internal and sickly. Alan was in a state where he realized he couldn’t function; it was his awareness of the effect of the drugs that I think took him to an edge. It wasn’t about his persecution—it was about him not being able to carry on at his capacity, something altered in him.”

While this may be true, the film makes crystal clear there was no end of manipulation, mendacity, and pressure on Turing from the establishment both during his years at Bletchley Park and beyond. At one point, he was even under scrutiny as a suspected Russian spy. There is no question that the issues raised about the relationship between the state and the individual in The Imitation Game run very deep in contemporary waters (lest we forget the mysterious suicide of the British Iraq weapons inspector David Kelly in 2003). We are living in an era when the far right are making considerable gains in Europe and a Russian megalomaniac is encouraging rampant homophobia across the plains of the Great Bear; an era that bears some semblance of the future postulated by Anthony Burgess in his scathing treatise 1985; and an era in which Great Britain (or perhaps Orwell’s Airstrip One) serves as a refuelling stop for U.S. planes carrying terror suspects to clandestine torture chambers.

Such considerations about our contemporary paradigm mirroring The Imitation Game are far from lost on Cumberbatch, who is no stranger to sticking his neck out nor to playing those we deem as geniuses, having made his mark playing Stephen Hawking in a BBC dramatization one decade ago (he has since been a longstanding ambassador of the Motor Neurone Disease Association). “There are very similar ingredients now to what was swimming around at the beginning of the Second World War, and again, it’s all born out of economic crisis,” says the actor, who, it is also worth noting, was an outspoken member of the Stop The War Coalition and is a campaigner for the equal rights of women in Afghanistan. “It’s depressing how familiar the themes are, and the suppression of these minorities. The arguments are very complex, of course, but I think it’s very easy to scapegoat minorities of any form at a time of crisis. Greece is the birthplace of democracy and civilization in Europe, and, ironically, Iraq is the cradle of it in the Middle East—look at what’s happening in both of those countries. It’s the same in Russia. Russia is just extraordinary. It’s really shocking.”

As the man who played Julian Assange in The Fifth Estate (from whom he actually received an open letter), Cumberbatch continues his plunge into characters surrounded by string-pulling machinations of the establishment and military-industrial-complex. So, where does the man described by Time magazine as “one of the most influential people in the world” (no pressure) look for a genuinely objective analysis of contemporary issues, given that the sensationalist fast-click sound-bite culture (inextricably linked to the rise of the digital age, somewhat ironically) is said to be fundamentally affecting our attention spans. “It is very easy to get lost in the sound bite, rather than investigate a story fully,” he admits, as our ride approaches its destination, in the now pouring rain (such is the schizophrenic reverie of London weather). “I think I am quite old-fashioned, though: I read around a subject if something really grasps me. I know there are certain sources of information I can go to for less corporate interference or politically biased editorial. There’s a website called Online Democracy Now that’s fantastic, for example. I think we’re savvy enough now as readers and consumers to be able to filter what the bias is; what kind of base a proprietor is trying to establish politically in order to pedal his version of the truth. I don’t think anyone picks up the newspaper these days, especially post-Levinson, and thinks it is cast-iron fact—we understand what the media echo chamber is.”

One could take a rather bleak outlook on contemporary global affairs, and given the hope versus absurdity paradox, where does one look to in the modern game of life for the hope that so obviously eluded Turing, who was not a man given to pandering to the political miasma of his era? “We still have rebels that are just as inspiring,” says Cumberbatch. He’s seemingly an eternal optimist, which one could assume underpins much of his drive to commit his time to humanitarian causes. “There is still magic. I think the defence of democracy and the work of UNICEF and Médecins Sans Frontières is just astonishing. It involves men and women every day putting their lives on the line for their belief, to turn a potential human tragedy into something stable, or transform a state facing the tide of war to a state of peace is a magical thing to try and achieve.”

The car pulls up outside Cumberbatch’s next media rendezvous at London’s Barbican Centre, and sadly there is no more time to delve into the arena of ethical philosophy. All that remains to ask is what makes Cumberbatch so resoundly committed to carving out roles in culturally pointed works that make indelible marks on the collective consciousness, which, rather unexpectedly, takes us swiftly to the lyrical vistas of Belinda Carlisle via the poet Alfred D. Souza. “I personally believe that heaven is on earth,” says Cumberbatch with a smile, as we alight the car to be handed umbrellas by the driver. “That’s one of the mottos I live by: dance as though no one is watching you, love as though you have never been hurt before, sing as though no one can hear you, live as though heaven is on earth.” And with these words it’s a handshake, a smile, and a walk into the London rain for me to consider whether anything we have discussed will make a difference to you when you read this, or whether this piece is essentially just another footnote in the infinite library of the absurd. In the words of Belinda Carlisle, “Do you know what it’s worth?”

Photographer: David Goldman for ThePureAgency.co.uk.

Fashion Editor: Rose Forde at RoseForde.com.

Groomer: Tyler Johnston for Onerepresents.com using Schwarzkopf professional.

Producer: Emily Wardhaugh for ThePureAgency.co.uk.

Photography Assistant: Alice Whitby.

Styling Assistants: Indigo Goss and Julien Koestel.

Location: The Stag, Hampstead.

Special Thanks: Camilla Arthur at CamillaArthurCasting.com.