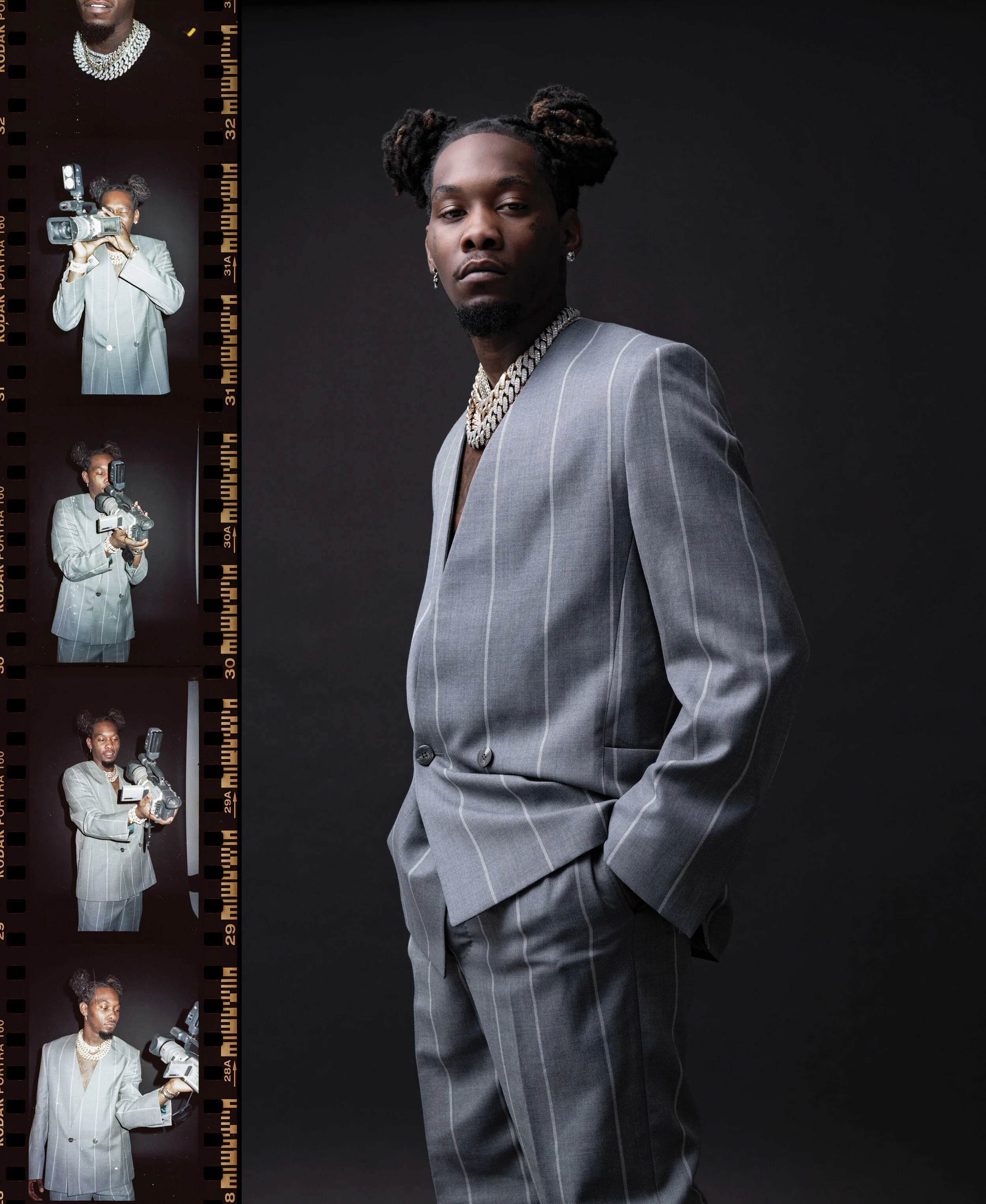

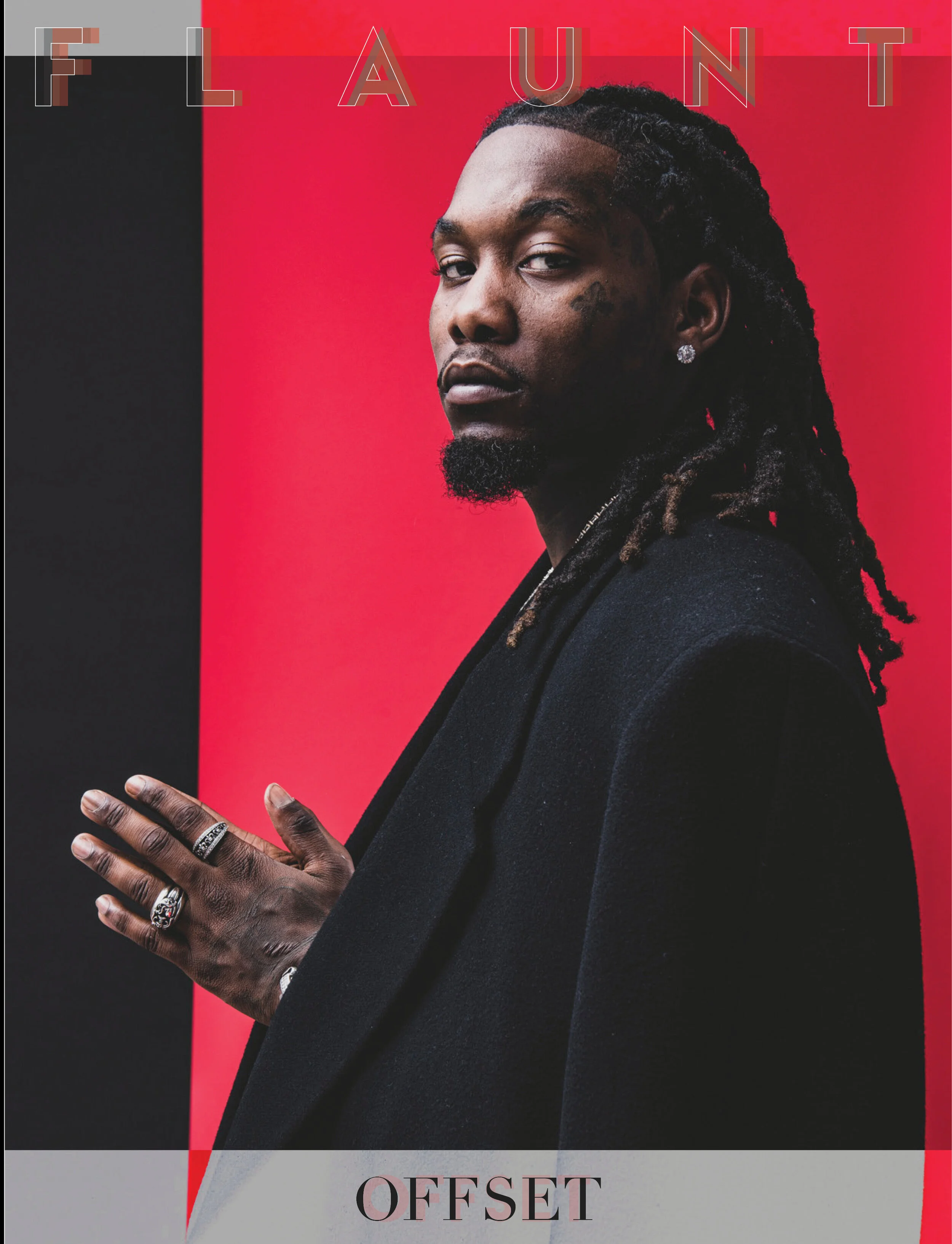

Offset / A Vice Grip On That Wishbone

by Sun-Ui Yum

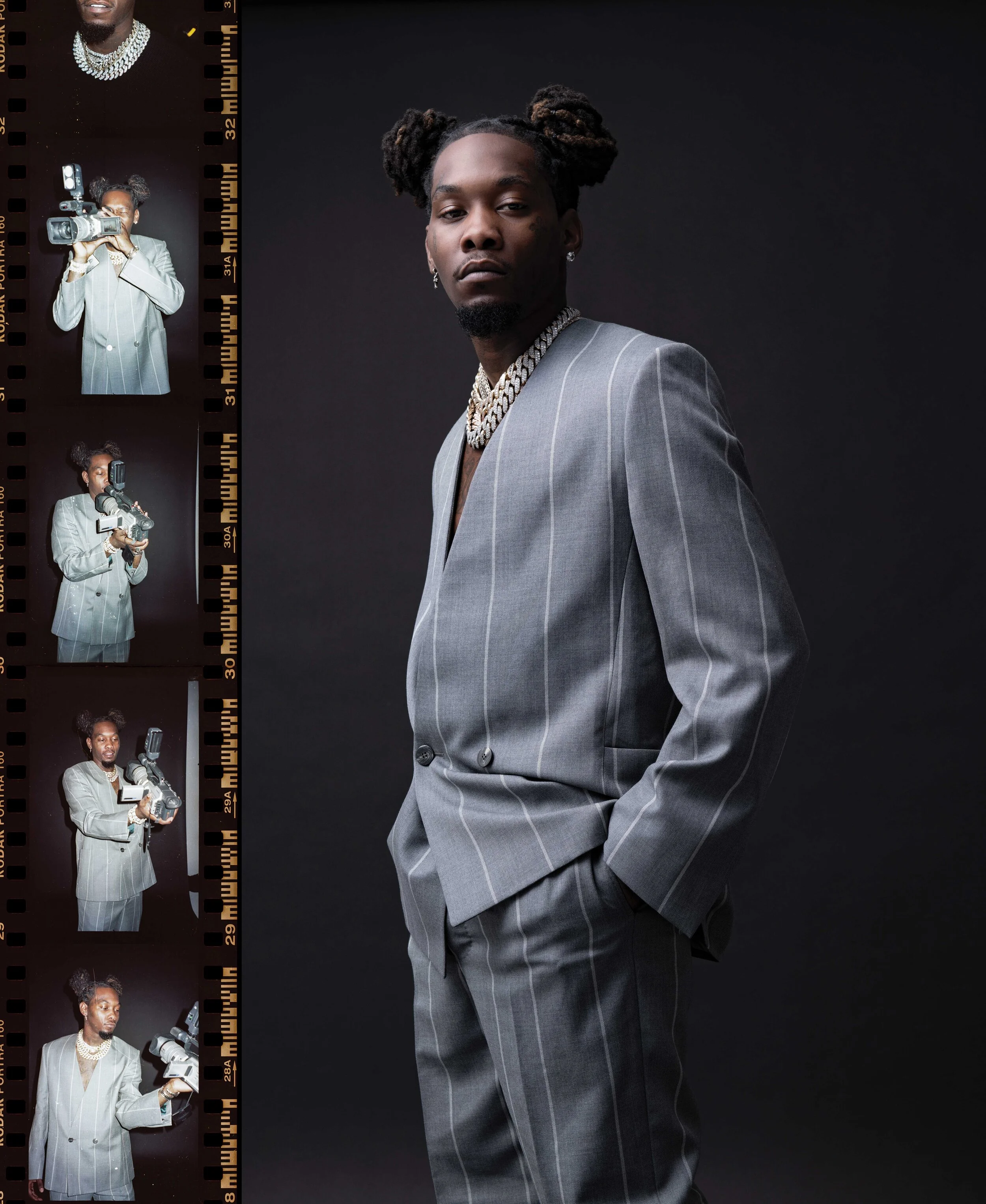

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

It wasn’t supposed to go down like this. We might’ve foreseen many different iterations of 2020, but few would’ve been so fractured as the cracked road ahead of us—part pandemic, part unrest writ large into unrest steaming off the streets. Touch points dissipate by the second, and reality’s blinking continues to slow.

And just five years ago—a post-apocalyptic blink of an eye—it would’ve been unthinkable to imagine Migos would’ve become our great societal constants: elder statesmen of rap. There, too, fate hasn’t broken in the direction we might’ve anticipated. For several years, Quavo was the pick du jour to transcend into solo stardom out of Migos—a suave, grinning translation of an inescapable Atlanta tidal wave. Offset, conversely, existed precariously, seemingly out of sight for each of Migos’ breakthrough achievements. He was a symbol both tortured and enticing, a magnetic voice that personified the group’s attrac- tions but also their insecurity. He was their most unknowable; now, he is indelible.

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

In the wake of their gravitational album, CULTURE, and Migos’ second-wind, Offset has managed to establish himself as an elite, inescapable presence that exists in rarefied millennial air. Most pivotal was their phoenix awakening out of pop culture purgatory, propelled by the most crystalline, back-to-back singles of the last decade (the world-stopping “Bad and Boujee”, straight into the anthemic “T-Shirt”). When we speak over Zoom, Offset’s pride still seethes. “You might have been a believer seven years ago,” he reflects to me, the stare smoldering, “but there were definitely a lot of disbelievers seven years ago, too.”

Anyone with even a cursory attention span ought to know that Atlanta has been the churning engine behind rap since the early-to-mid-2000s. But shortly past the turn of the past decade, Migos became a different type of emblem for the new rap order: dissectible charm, bellowed proclamations, instantly iconic. They were meteorites—yet newfound stability is welcome but uncomfortable garb, borderline antithetical to the very substance of their genesis.

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

By the late 2010s, Migos were cemented as essential presences in both Joe Budden dust-ups and failed Democratic presidential campaigns. In the post-dab society of which we inhabit, Migos are cosigners rather than the cosigned. No longer content to simply serve as external tokens of authenticity (someday, an inevitable Drake retrospective will correctly attribute the “Versace” remix as a narrative-shifter, a steely about-face post-Take Care), their voices now serve as constants, stabilizers, instant validators for rising rappers.

And while Offset is a natural foil for Quavo and Take- off—the coldest blooded of the three—his best qualities are most clearly called upon when juxtaposed with a deliberate essayist like 21 Savage on their collaborative album with Metro Boomin. The raps have always been geometric, diamond-cut edges and iced ad libs. During his best stretches (such as his earth-shattering verse on Gucci Mane’s “Met Gala”), he adds intricacy; the effect is angular and kaleidoscopic, an assault from all downbeats.

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

As a collective and as solo artists, Migos were always prone to hitting stretches of Autotuned autopilot; the breakneck second gear of Offset has always been a difference-maker. It’s no surprise that on the run-up into CULTURE that re-established Migos as premier rap frontmen, Offset was a dominant presence. His iconic turn on the hook of “Bad and Boujee” was instant elevation, proof of concept. A couple years back, he slipped to the New York Times that he wasn’t originally on choruses because he felt he couldn’t handle them: “I just felt like I had to get better at my craft.” Box checked.

The release of last year’s solo effort, FATHER OF 4, was a patented move—the opening of previously closed doors, the baring of a hardened soul—and a successful culmination. Here, Offset finds nimble melodic registers, softened echoes of steeli- er past proclamations, and begins to color in a legend previously only inscribed in stone carvings. In any case, the trajectory was clear even before marriage and fathering a daughter with Cardi B—perhaps the most iconic female in music today not named Beyoncé or Taylor Swift—entered the picture.

***

There was a stretch where we were never more than a couple weeks removed from the latest Migos single, and so the relative quiet of the collective as of recent is particularly glaring. We are just months removed from the three-year anniversary of CULTURE II, and dangerously close to two years since the third installment was announced. It feels darkly reflective of the tenor of the last few months, paralyzingly unfamiliar societal discord masked by silent street fronts, a world frozen in a hiccuping loop. So many of our familiar touch points (family, friends, daily routines) have dissipated into smoke; the group’s relative silence feels like yet another reminder that nothing at all is the same.

But for Offset in particular, there’s a sense that this is the new normal: measured movements punctuated by explosive conjurations. The long-awaited solo album last year, the launch of his Laundered Works Corp. fashion line at Paris Fashion Week earlier this year—quiet celebrity suits.

After all, part of what made Offset’s original trajectory so murky, in particular, were the legal troubles—possession of firearms, battery, gang charges—that felt so fundamentally intertwined with his career. Five years ago it was more common to hear his name as a part of refrains shouted for his freedom than from his own ad libs, and for a particularly dark stretch between 2015 and 2016, his own personal fate felt inexorable and grim, even as the group’s constellation rose. Offset offers up his own duality to me unprompted: “I’m on both sides. I’m very successful, but I’ve also been very unsuccessful, and in trouble.”

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

So for a moment, the stability Offset has earned in this unnaturally quiet stretch of modern life feels like something worth soaking in and savoring: “Having that day-to-day has helped a lot with family; you’ve got to spend time together and create a vibe,” he says. “I always record at home, so it’s the same feel. I never got any vibes out of recording from big studios.”

This is all poetic glow from a distance but significantly grimmer history to confront head-on. You can’t really tell if someone leans forward when they are joining a Zoom from a car, but that’s what it feels like when I ask Offset about his own personal experiences with race relations. “It’s a million times,” he says, head shaking, his words girded by newly-forged steel. “I sat in Statesboro for my security having a firearm in his name. They held me for eight months without a bond, and made me plea out to another charge to get out.”

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

The list of anecdotes that follow stretches long—friends from school, family, acquaintances held for 40 years, others killed by the police. He’s more reticent when it comes to his own history but his viewpoint is crystal: “Me, even as an artist, some places I go police want to pull you over just to see your car. Police officers just want to stop me.”

Multiple times as we speak, he channels our conversation towards voting, a clear fixation—not just as an individual action with impact, but as a qualification within society, microscopic proof points of existence and acknowledgment. It’s the first thing he mentions when I ask about social action and what he circles back to after musing on racial profiling. “I didn’t even know I was eligible to vote until this year because of some of the mistakes I made when I was younger,” he says, tailing off. “Some people just don’t know they can participate in the society we live in.” Watching Offset untangle the grim irony in that self-evident statement is a bit unnerving.

“I think every Black person should be given a million dollars,” he says to me later, tongue-in-cheek but only barely. “At the end of the day we have this struggle in America, and it’s only right. We spend all this money on bombs and weapons we don’t use—we might as well spend that money on the people, programs that help Black people own houses.” The subtext of his own troubles are inscribed on the backside of every word.

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

***

While the most commonly trafficked narrative around him is newfound maturity in fatherhood, it’s easy to forget that this is not a “could have been him” story for Offset—it was him, for years. The success came in spite of, not avoidance—not a newly-recognized choice, but instead a role he was forcibly distanced from.

When I ask Offset about his state of being amidst the pandemic, I am met with equivocation. “It’s been a hard time, just because it’s not one of those situations where it affects just one group of people—it’s everybody’s problems,” he muses. “It’s weird in public, seeing the masks, and my great uncle passed away from it. Virtual performance is hard because the people can’t be present. A lot of new things.”

The debut of Offset’s fashion line this past January came to fruition amidst hallowed, sprawling church hallways. The guest list—Tyga, YG, Paul Pogba, DJ Mustard, dozens of others—was equally ready for Vogue and DJ Vlad, a celebration. When I ask Offset about the experience, too, he skips right over pride and fulfillment right into gratitude, more fixated on those who sup- ported the line than the line itself: “Diddy bought a fur jacket that was five grand. A lot of my big bros, Black brothers in hip- hop, supported me strong.”

His framing of his fashion debut, too, feels partly like a joint concession and confession—unmistakably an apex achievement, the ultimate invitation into high society, but per- haps not the perfect one. Offset tells me, “Even overseas, I’ve heard and experienced mistreatment from the fashion world. For us to do that in Paris, our first year releasing our things...” He tails off.

Right about now, I can’t shake the notion that Offset wants to be seen. His ability to negotiate a license to exist and op- erate in traditionally exclusive spaces (fashion, American pop culture, American society) was by a razor thin margin. In the past, he’s betrayed more exhaustion, telling GQ last year that “I’m famous, but at the same time, I’m a human. I go through the same thing you go through, but maybe to a different extent. I just want people to know I’m not perfect. I’ve done wrong things, but I’ve become successful, I learned from the wrongs.”

FEAR OF GOD EXCLUSIVELY FOR ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA

Offset asks me if I knew that at one point in history, you couldn’t buy a house if you weren’t white. “I didn’t know that was how areas were controlled—generational wealth through family,” he says. The previous precariousness of his own success is obvious subtext.

Ultimately, I suspect this is perhaps the most cogent distil- lation of Offset’s legacy: he was able to remain seen within the collective psyche without compromise. He and the rest of Migos are subsumed into popular (even political) culture when expedi- ent, but compartmentalized when the actions are less palatable.

Towards the end of our conversation, Offset says to me, “People pass away and they get so many followers—it’s backward.” The nature of his superstardom today is relational, scrutinized; in the floating ether of digital existence amidst a pandemic, his celebrity feels ethereal. For a dangerous two-year stretch, it was mortally endangered. Fate wasn’t always kind—but as we all know, fate breaks both ways.