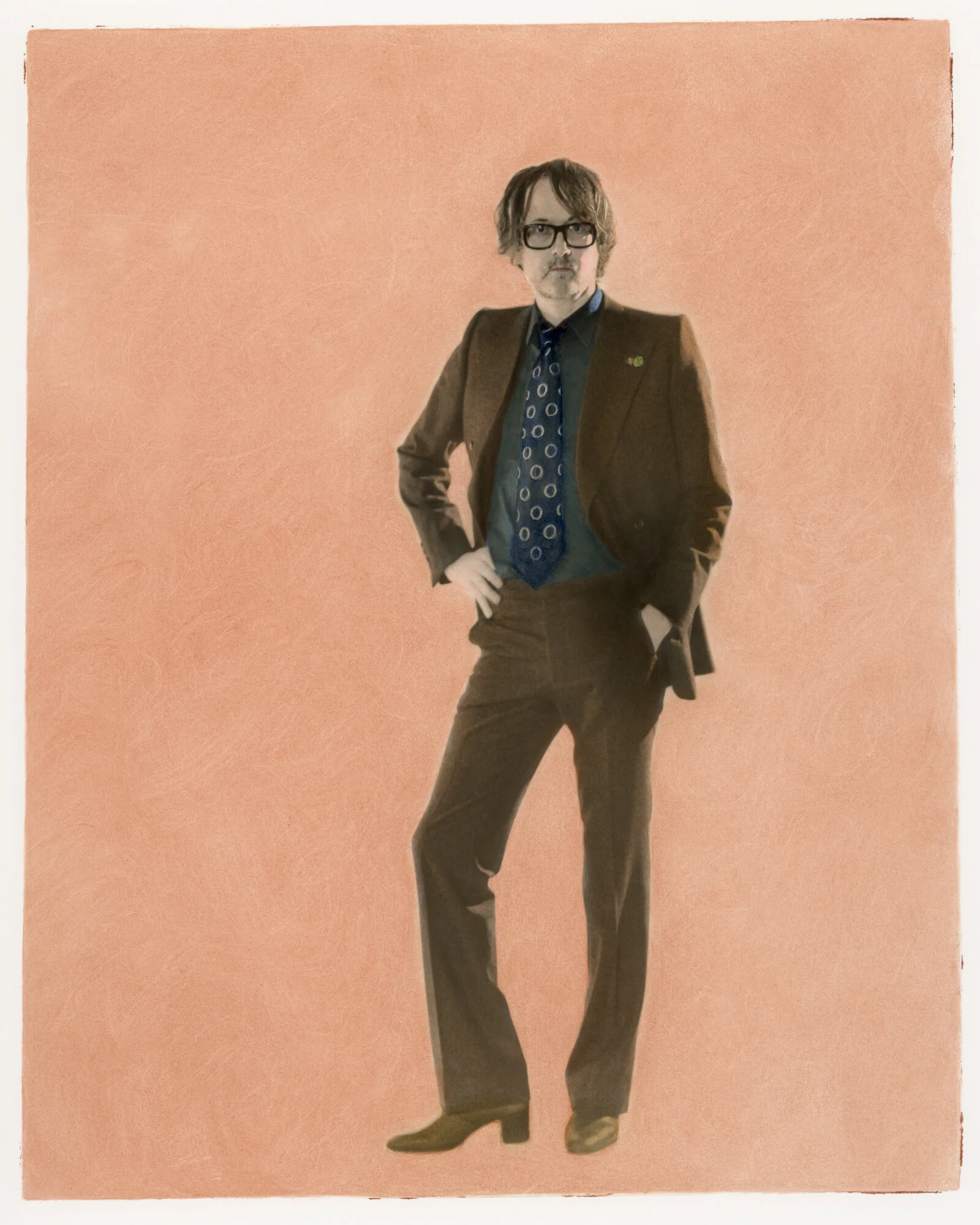

Jarvis Cocker / A Collapse, an Ode to Joy, a Bedtime Story

by John-Paul Pryor

Art by: Linda Schoonover

“Jarvis… Jarvis… Jarvis!! The phone!!” shouts the incrementally more exasperated sounding voice at the end of the line, which I can only assume belongs to the girlfriend of my interviewee. The tone seems somehow entirely fitting for the testing times in which the phone call is made, when people either singularly or in small nuclear groups shelter in their homes from a global pandemic, no doubt driving each other, or themselves, more than a little crazy. I hear a muffled reply, and wait. Listening back to the recording, it seems that during this moment I am mumbling something surreal to myself—somewhat emblematic of my own mental health response to the invisible virus that has flung the world into varying paroxysms of strangely calm societal chaos. When Jarvis Branson Cocker does come on the line, it takes us both a couple of minutes to break off our respective reveries and remember why we are meant to be talking at all, and we both faff about for at least a minute turning off our radios, both of which seem to be tuned to the quintessentially comforting British soma of BBC Radio 4. “Okay, that’s good, I’m relaxed now…” he says in the dulcet Sheffield drawl that has defined a career encompassing sardonic pop stardom, outsider art documentarian, radio host, and bedtime story reader to a nation that hold him about as dear as they do Heinz Tomato Kethcup.

As it turns out, we are chatting because he is about to release a brand new album entitled Beyond The Pale under the band name Jarv Is. The record is the culmination of an innovative collaborative musical project with some of his musician friends—but more of that shortly—and it’s already been received as somehow weirdly prescient of the global situation at the time of print, with the second single from the album “House Music All Night Long” describing housebound frustration and containing the refrain: “One nation under a roof, ain’t that the truth…” It seems bizarrely on-point, given it was recorded months ago. “I’m definitely not Nostra–Jarvis or anything like that, but the lyrics do kind of describe the situation that we're in now—that sort of cabin fever feeling,” says Cocker by way of explanation. “The weird thing is that that song was written about a period a couple of years ago, where I was stuck in London one weekend. It was nice weather and pretty much everyone I knew was at a rave in Wales. I was stuck in the house on my own, feeling sorry for myself, and I got myself out of it by writing a song. Now, through some weird, crazy coincidence, it has ended up describing something that everybody's feeling. I guess that is kind of the beauty of creativity. You never know what the results might be.”

Most chaos theorists would also postulate that we can never know the cause-and-effect of the magical ‘butterfly effect’ coined by the meteorologist Edward Lorenz–you all know the one: a butterfly flaps its wings in Wuhan, China causing Donald Trump Jr. to shoot up bleach on the other side of the planet; that kind of thing. The process and random sequential potentialities of creativity are something that fascinate Cocker, who has a book coming out on the subject of the creative mind in the fall–and it’s interesting that even lockdown in a global pandemic is something he sees vast creative potential in. “I'm looking at the lockdown in the respect that creative people have got an alternative state in which they can actually make something,” he says. “And the joy of that is that when you're in the creative moment, and you are making something, then time just seems to slip away, and you get lost in that moment. I think that's why we create…” He pauses. It’s not done for dramatic effect, but it’s kind of perfect. Cocker is a master of the pause, as anyone who has followed his freeform late-night forays into the human condition Wireless Nights on the aforementioned Radio 4, or his excellently shambolic lockdown show Domestic Disco, will surely attest. “Years ago, I did a series for Channel 4, called Journeys Into The Outside,” he continues. “I was looking at outsider art, and, of course, the question that I asked the artists every time was why–why are you making this? Why have you built this big psychedelic mountain in the middle of the desert, or whatever? And that was the one question that none of them could ever answer. The penny finally dropped to me that the reason they couldn't answer that question was because it was something they never asked themselves–they got so much pleasure out of making things that why wouldn't they do it?”

Art by: Linda Schoonover

It’s an ode to joy approach to creating that has underlined the aforementioned album, which was recorded in a live spirit of innovation and experimentation—captured on the move, in a sense, and thusly described as an alive album not a live album. “I had some ideas for songs that hadn't really come to fruition, and I got offered the chance to play them at this festival Sigur Ros were putting together in Iceland at the end of 2017,” he says, describing how the whole thing came together. “I was just at the point of turning it down because I didn’t have a band or anything, as such, and then I just thought, ‘Fuck it, I'll do it.’ I got a band together quite quickly. Serafina Steer plays the harp and sings—I had worked with her before–and she kind of came with Emma [Smith] who sings and plays violin. I thought Adam [Betts] and Andrew [McKinney] would be a great rhythm section, and I had worked with them when I did this thing of singing Scott Walker at The Proms. And then there is my friend Jason [Buckle], who I had been in a band with called Relaxed Muscle. That one performance went well, so we decided to carry on. The songs were skeletal ideas, but flesh got put on the bones by playing them to people, so the next stage was a very small tour of the UK, and we just recorded the concerts as we went along, so I could kind of monitor how the songs were developing.”

These live desk recordings came to form the foundation of the record, with in-studio overdubs, and it’s perhaps an ironic flip in that while the record has a vibrant organic feel, it’s not something that will be likely to have a live audience any time soon, at least in the UK. The band is still busy, nonetheless, and their creative process continues to be innovative. “I’ve been trying this technique in lockdown, which is a real revolutionary breakthrough for me,” says Cocker. “What we have been doing is a bit like that game where somebody draws a head on a piece of paper and then they fold the paper and they pass it to somebody else, and then they draw the body, then someone else draws the legs…. We’ve been trying a musical version of that, sending ideas to each other. I don't know if it will ever see the light of day, but that's not really the point. It's more just that we're having fun doing it.”

The album is great, encompassing elements of the emotive Scott Walker-esque narrative style Cocker is celebrated for, but also feeling a little like a throwback to the early Pulp of Separations, an album recorded a good while before fame came knocking. It’s first single, which tackles the challenges of the relentless march of time “Must I Evolve” has already been nominated for track of the year in this years Q Awards. But music industry accolades are an aside. It’s the in-the-moment joy of the creative process that drives Cocker, who, to be fair, has always seemed pretty un-phased by fame and celebrity, and he thinks society might just be on the cusp of a return to making art for personal fulfillment rather than financial gain, recognition or global money laundering. “You have to realize that it’s enough to make stuff, and that's the point of it,” he says. “I think that's why people are more interested in outsider art now, because the art-world has spiralled out of anybody's comprehension and become kind of an investment opportunity, which goes so far away from that primal impulse to just to make something and get pleasure from it. We’re back to creativity in a kind of natural state right now, because everything's on pause.”

Art by: Linda Schoonover

But isn’t it hard to find motivation or inspiration without the input of external stimuli, sat alone in your space with the world outside ticking along in a seemingly perpetual limbo? “Well, I always quote this thing that Quentin Crisp once said in a TV interview,” says Cocker, when I pose this to him. “He said, rather than looking outside and thinking, is there something I haven't experienced, or haven't seen yet? Why not look inside yourself and ask the question, is there something that I haven't unpacked yet? We’ve got as much of a universe inside as we have outside. I feel like we're coming to the conclusion now that this is a time for people to discover that. You can't go out into the outside world right now, so why not explore the inner world—you know, look at this stuff and see just how much you contain. Who said, I contain multitudes? Is that William Blake?” I agree it is Blake, entirely unsure as to whether it is, but it definitely sounds like it could be. Upon checking for this article, I find out it was actually Walt Whtiman who said that, so props to us both for being so literary. The point seems salient enough, though—that we can all undertake some kind of metaphorical journey into the cocoon of our being and come out again all fluttery and multi-coloured. But is it really likely there will be lasting cultural changes, or when all this is over will we return to our usual mindless consumerism and the horrors of Celebrity Love Island and Instagram Influenzas?

“I think it's an interesting point in time, and some people have said that maybe the world will be divided into before the virus and after the virus,” says Cocker. “I don't if that's true, but I do think we've never had a situation like this in our lifetime, where the whole world hits the pause button. It's kind of enforced time for contemplation, and I don't think it's facile to say that it could be a positive thing in some ways—not positive if you've got it, obviously, but positive in that its a time to take a breath and just think about things. It’s like everyone has to have a very close encounter with themselves, and you can use that to find out something—what do you want to do with your time, how do you entertain yourself? It reminds me a little bit of flying…” And at this point, Cocker drops perhaps the best analogy I’ve heard so far for the mass quarantine that has defined the first half of 2020: “There’s always a point in a long transatlantic flight where you've watched maybe one or two films on the in-flight entertainment system, you can't face watching another one and you are just sat there with yourself and your own thoughts. And that's really what's happening now. There's no shortage of entertainment options that you can access but there's a fatigue that comes with it, and I think everybody is now realizing that it's just not enough, and that it’s actually pretty boring what we crave—in fact, what we're really feeling is the lack of interaction with other people.”

Art by: Linda Schoonover

It’s a fairly ironic truth-bomb given the way society has raced forwards in the last 20 years towards us all becoming ever-more isolated units of one-click consumption. “It’s been interesting, because of that the movement in society towards a kind of self isolation,” says Cocker. “You know, you don't go to the cinema; you just stream the film into your house. You don't go to a restaurant; you just get food delivered. And it’s like that kind of atomization thing, where I guess people thought: ‘Oh… This is great. I can just do my own thing and I don't have to worry about anybody else.’ Then you find that if you get into that state of splendid isolation, it's actually really, really dull and boring, and that what actually makes life interesting is other people.”

The realization that isolation sucks has been a tough moment for most of us, and you’ve got to hand it to Cocker for putting some heart and soul in helping people get through it—the Bedtime Stories he shares on his Instagram, being no exception. It’s a pretty relaxing experience to drift off to Cocker reading authors as disparate as Richard Brautigan and Tove Jansonn. “They’re just great books, you know?” he says, when asked why he was keen to get them out there. “When this thing started, I found that I wasn't sleeping so well—you know, you're worried about stuff, and you just pick up on the general weird atmosphere within society. So, I thought this could be a good time to put these stories out again [many originally aired on his BBC Radio 6 show Jarvis Cocker’s Sunday Service], and maybe they'd be helpful for people, because whenever I read a story to my girlfriend, within two minutes she is fast asleep. I think I've just got a voice that can send people to sleep, so if it helps people through when they're having trouble, then I'm happy to do it.”

Art by: Linda Schoonover

Well, what can you say to that but thanks. I can tell you, as a long-time sufferer of insomnia that Jarvis Cocker’s Bedtime Stories are something of a godsend. I wonder, as we draw our tortuous conversation to a close, whether the process of creativity on all levels is cathartic for him. “I guess what I’ve done all my lifetime in writing songs is, in a weird way, fulfil a sense of missing something,” he says. “If you imagine a jigsaw puzzle, and there's a piece missing, which is really irritating—well, if you feel that in yourself, songs can sometimes plug that gap. And the thing is that unfortunately they probably never quite fit that hole—they do it for a while and then eventually you have to create a new one. It’s like you've got this stuff going on in your head and it's driving you mad, but if you turn it into something, you externalize it, and, in a way, you neutralize it as well, so it can't have a toxic effect on you anymore…” Cue another pause from the king of an-ti-ci-pation… “That said, it’s an on-going process, and you just have to keep hoping that you're headed in the right direction—and that's the best you can hope for, really. There's no such thing as eternal, perfect happiness, but there are moments of pure joy and happiness we can access. I believe in them and I've experienced them, so I know that they're there. And sometimes you can really despair of those moments ever happening again and you think, ‘Oh well, I wish I'd never been up here, because then I wouldn't realize how miserable I am.’ That's a bad way to think. You’ve just got to keep going.” And with that little gem, I suggest that no matter how beyond the pale the world may seem right now, you had also better get out of bed and put the pedal to the proverbial metal, brothers and sisters…

Written by John-Paul Pryor

Photographed by Chris Schoonover