Gary Simmons | 'Remembering Tomorrow' at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles

by Constanza Falco Raez

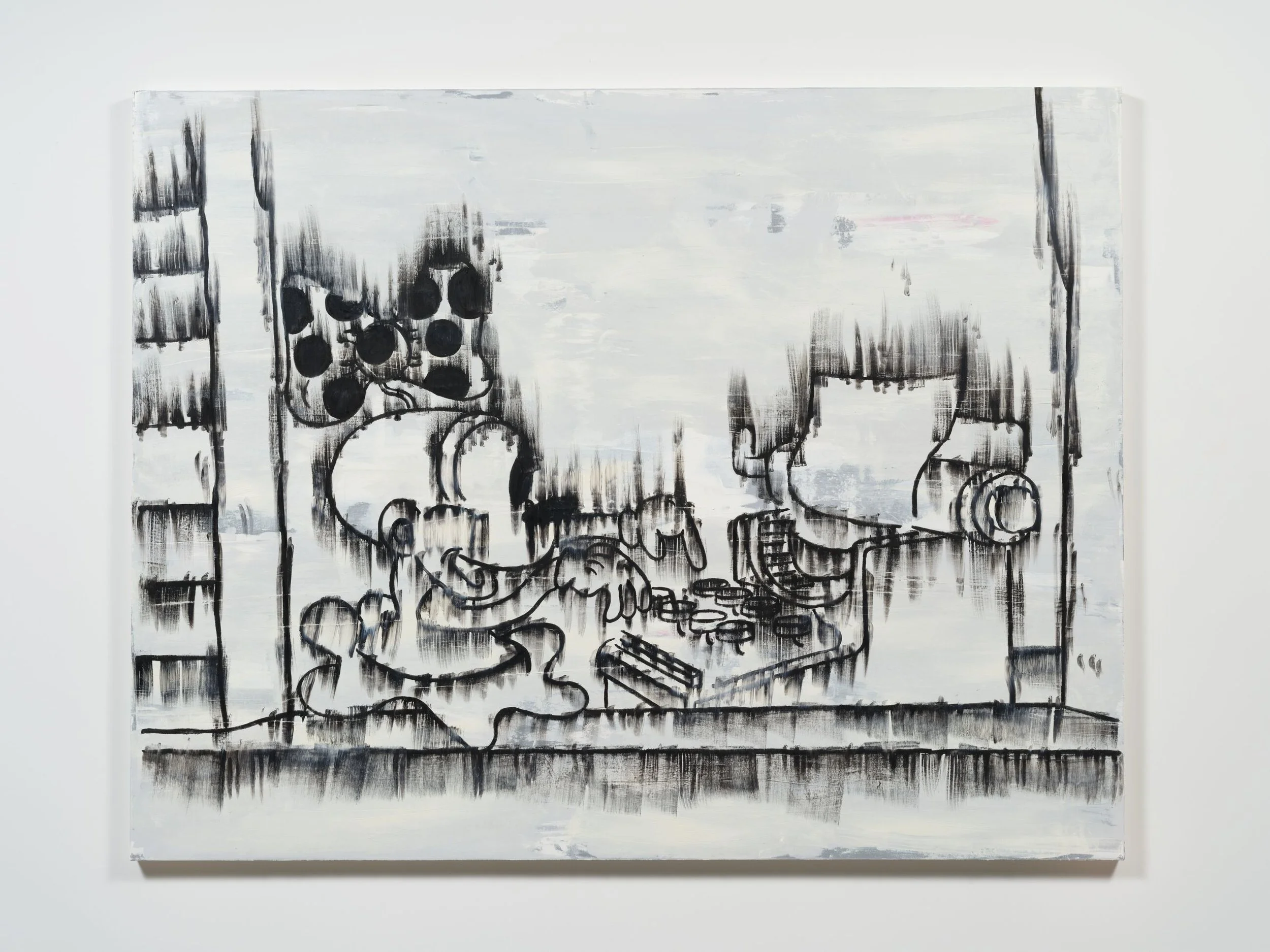

Gary Simmons. “Splish Splash” (2021). Oil and cold wax on canvas. 84” x 108”. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Hauser & Wirth presents Remembering Tomorrow, Gary Simmons’ first exhibition with the gallery, which will span both North Galleries and the outdoor courtyard starting February 17th through May 22nd, 2022. The exhibition will present new paintings, wall drawings, and sculpture, as well as the famous installation ‘Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark,’ originally created for Prospect New Orleans in 2014 and presented for the first time in Los Angeles now.

For over 30 years, Gary Simmons has examined American history and popular culture to analyze themes of race, identity, politics, and social inequality, and make a commentary thereafter. This new exhibition includes four new massive wall drawings created onsite that continue those conversations started years ago employing the same erasure technique.

Flaunt conversed with the artist about his beginnings, his memories, and the ultimate question he is asking through his art.

Gary Simmons. “From the Mountain Tops” (2021). Oil and cold wax on canvas. 120” x 108”. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Gary Simmons. “Lindy Hop” (2022). Paint and chalk on wall. 144” x 535”. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

How did you start making art?

Probably from the time I was really little. My parents really encouraged me to make as much art as possible. My dad was a fine-art photography printer, so he did a lot of big books for big photographers, and people like that. And so I was always around a lot of folks, you know, Garry Winogrand, Ansel Adams, and people like that, from a very young age. I saw, professionally, how it was made, but I was always interested in art. Two things I was always interested in were playing baseball and making art, so I think it’s always been there.

Your art makes a commentary on race and stereotypes in American popular culture, what drew you to wanting to make these commentaries and this type of art?

I went to school in the 80s, and a lot of my teachers were very well-known minimalists and conceptualists and I really was drawn to that kind of work, but I did not feel like there was a place for me, or people that looked like me. And so I really kind of felt the coldness of minimalism or the cerebral nature of conceptualism was something that I was very drawn to but I wanted to personalize my experience through that lens, so that is kind of where it all started. And I think that because there were so few artists of color at the time, that voice, that need to find either a political voice or something that referenced otherness, was the starting point for where my work started.

Talking about these icons and stereotypes of American culture, how do you choose them, and what meaning to give to them, and what message to send through them?

I think that a lot of the work started through thinking about childhood, and thinking about where people learn to think a certain way drew me to childhood. And I started to think about cartoons as this area where parents would sit their children down in front of cartoons and walk away, and not really have the time maybe, or whatever, to look at what children are looking at. I think that whether it be violence, or politics, or something, those things are all inherently in cartoons. That was the start. I realized looking at cartoons was a very formative, certainly for me, way of looking at the world, because these different characters that were represented by a rabbit or a really funny duck or something like almost carried underneath them the representations of what those characters or little bunnies, or frogs actually would be. They started to construct these stereotypes. So the frogs might have these really big lips and huge eyes and they would speak a certain way and you know that they were supposed to represent black folks, or a mouse might be really drunk all the time and lazy and they would represent another group of folks. So it really had an impact and effect on me. So I started to really be interested in digging out some of those early images and play with them. And they are so palatable, they are almost friendly in appearance, but underneath they have this kind of sinister aspect to them, so I try to create or look for images that have dual meanings. Images that at first appearance might have a funny or beautiful appearance to them but underneath there is this almost evil to it. And I think a lot of those early cartoons had that, so that’s where a lot of that comes from. I think I still look for those kinds of issues hidden, like I look for things that have dual meaning to them, or that can represent something else other than what they appear.

Gary Simmons. “Rogue Wave” (2021). Oil and cold wax on canvas. 108” x 120”. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Gary Simmons. “You Can Paint Over Me But I’ll Still Be Here” (2021). Metal, wood, mixed media, ink, enamel paint, cast resin. Dimensions variable. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

How do you think the work that you are creating affects you or heals you?

Particularly in something like the erasure drawings, where I’ll take an image, and it might be a racist image, and so I’ll redraw the image and based off of my response or how I am feeling that day or my emotions, there is an inherent violence to trying to obliterate or erase that image and that is where I think the power of the work exists. Because what I am trying to do is erase a stereotype, but it’s sort of futile because as much as I try to erase it, there is always going to be traces of it left behind, and that is where the work sits. And this act of erasure is something that is threaded through everything that I do, whether is making a sculpture, or a music piece, whatever it is, there is always this action to try to create a space that hovers between representation and abstraction, and the viewer has to fill in those gaps in between.

Yes, I was going to say that there is obviously power to erasing this thing that you have been seeing your whole life and being able to change it. And it obviously is still there, it still stays there, but you are changing the meaning of it. You are rewriting what I don't know if it's memories or history.

I think it’s both. I think memory is an interesting thing. I think we reconstruct our memory. We reconstruct romantic memories and we reconstruct horrific memories, and there is no such a thing as a true memory. I think if you remember the first time you were in love you highlight all the good parts and you tend to forget the bad parts, you know. And then if you have a bad relationship you almost remember only the bad, and never the good, but there was a reason why you were with that person to begin with. So we have this way of preserving aspects that construct who we are while trying to erase the bad parts. I think oftentimes you find people that repeat their own history over and over and that is where it gets really interesting. ‘Why am I behaving in the same way that I did that time again? What is it about me?’ I think that is when people turn inside and look at themselves and say ‘what am I getting back together with another nightmare person?’ And so there is that blurring between the two because you say to yourself ‘this time it is going to be different’ or ‘I will learn from the past and I know what to look for’ but no you don’t, you really don’t. I think that is where the work sort of hovers. Where those traces haunt you. They stick with you and they are part of your history, so you carry those with you.

And I think, particularly in Black history there is so much of it that has been erased and is dependent on an oral history or retelling of history. I can remember certain memories that are constructed based on stories that my grandmother told me. And I would look at a photograph, or she would show me a photograph of some place I was when I was little and she would tell me the story of what was going on that day or around that time, and that memory of that photograph became so real, the story that she told me, that it became my memory. And so now I look at it and I will show it to somebody else and I don’t actually remember it but I am retelling the story that my grandma told me while probably making up other parts along the way. So I think the work works in that way.

Gary Simmons. “The Lumber Jack” (2021). Oil and cold wax on canvas. 108” x 120”. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Gary Simmons. “Recapturing Memories of The Black Ark” (2014/ongoing). 11 hand-made speakers, scrapped wood, paint, and electrical components Dimensions variable. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Apart from drawing you also do sculpture and performative works and music, how did you start exploring all of those different artforms?

I tend to not think of myself as just one discipline, I don’t think of myself as just a painter or just a sculptor, or whatever. I think that is an antiquated way of looking at artists. I think it depends on what subject matter you are dealing with and hopefully you can apply your experience to it. So in the case of some of the music pieces, music has always had such an impact on me, historically, from the time I was a very little boy. My whole family is from the West Indies so music, and reggae music, and all still-band music, all of that is such a part of who we are. And you kind of use what is local to you in a certain way, you use things that are familiar with you that hopefully other people have an experience with, and so that is what I try to do. I try to create, or draw, or paint something that allows for the viewer to access it in their own terms. So if I draw a rollercoaster, I think that everybody has some experience of either seeing a rollercoaster, or being on a rollercoaster, or being in an amusement park at some point, and that thing that I am drawing allows for those folks to recall their own experiences with that image, or object.

So the speakers, the Black Ark piece, has a little bit of that. I created this stage with this Jamaican sound system that wherever it is invited to be installed I usually let those folks program the music that gets played on it, so at that point it’s almost out of my hands. Like I’ve created this thing that now gets activated when you invite other musicians to do what they do on this. So it is a point and space of activity, that other people can inclusively become a part of, and in doing that, creating a history to the piece itself. Conversely, we usually document every performance that happens on the Arc and that becomes part of this archival videotape and, in the show, it’ll be shown on a video-screen when there isn’t a band on stage, so you can see a certain band that played in London, or wherever, in the past, and understand that there is a history to this object.

Do you decide on the message or the medium first?

I think of myself as asking a lot of questions. I don’t think an artist can actually give the answers or solutions to something, but you can provide something that asks questions. And so I think I start there. I start with an idea and I will research that idea, and I do a lot of research, and that will lead me to another series of things, and I’ll allow for that to happen. I think that some of the best art that is made is usually made through mistakes or something that was unexpected, that you didn’t know. So I guess to answer your question, I start with a question or an idea, and then the material or the form that it takes is born out of that.

So in the case of the Arc, I was really interested in creating almost a living sculptural space. And a lot of times what dictates what I make is where this thing is going to take place, so I knew it was going to be New Orleans. I went to New Orleans, I was really attracted to New Orleans, I felt a real connection to the city. New Orleans is this incredible city that gets beaten down and then has this incredible strength to build itself back, and historically that is what it does. It’s constantly reinventing itself. And that is one of the reasons why I love New Orleans so much. So I really wanted to make an object that would inspire people through all of the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina, so we took and collected all of this wood and stuff from the 9th ward, where houses got completely destroyed, and we repurposed them and made them into these speakers. So that was the process of how that one was made.

The paintings and the drawings in particular are a bit different because I think that in that case I was really interested in how children are taught or how they learn certain stereotypes, so I went back and started to look at cartoons, and so then I started to carve and dig through a lot of the historical images that created why it was the crows or the frogs. So it is a hard question to answer exactly, because I think that it starts with a question and then the form comes after.

What ultimately is the question you are asking through your art?

I guess my ultimate question is ‘who are we?’ I think one of the most based questions that people ask themselves, or go to therapists for, is ‘who am I?’ And ‘why am I like this?’ And ‘how did I get here?’ There is a track and there are ghosts and there are trails and there are traces of the past that construct and create who you are, and you can’t erase them. It’s impossible. You are made up of all of those bits and pieces along the way that you’ve been furiously trying to erase. That’s who we are. We are who we are because of where we came from. And so that is probably the ultimate question of where my work stands or why I make it.

Gary Simmons. “Honey Typer” (2021). Oil and cold wax on canvas. 84” x 108”. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Gary Simmons. “Lynch Frog” (2022). Pigment and oil paint on wall. 144” x 381”. © Gary Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane.

In your work you speak about an individual memory and a collective memory, but you also see your collective memory depending on your individual memory. How do you think one affects the other?

How I even got to this is that I was doing a lot of cartoons that dealt with race, specifically, early on, and as I traveled I started to realize, through conversations, that people were isolating the work and anchoring it to me and my experience. And that frustrated me because I was like ‘you are missing the point.’ So obviously if you are missing the point then it has to be something else, like it’s on me. I am not allowing you to access my work outside of you just saying ‘well, that’s about him.’ And I wanted to create a way for other folks to access their memories and experiences through something that I created, so that was really important to discover about myself and the work. For me to really ask these questions I needed to find a way for avenues of access to be created, and that is something that sticks in the back of my mind every time I enter the studio, because an artist can sit there and say ‘I only make my work for myself,’ and I would sit there and say ‘that’s bullshit.’ Because the minute that you show it to somebody it’s no longer for yourself. You are looking for approval, you are looking for some response. Otherwise you wouldn’t show it.

I have all of my daughter's early little drawings and she would go outside the lines and all of that stuff and I would encourage her to go outside the lines, like do you man, do whatever you want to do, there are no rules in making art. But she had a teacher once that reprimanded her by saying that she wasn’t coloring inside the lines, and I got really angry because you don’t tell a kid that there are rules to this, and so I said to her, ‘baby, do whatever you want. If you want to color only outside the lines, go ahead.’ ‘But the teacher said…’ ‘I don’t care what the teacher said, your father said you can do whatever you want.’ And I think that’s true, you know, you have to be able to break some eggs to make an omelet, that’s just the way it is.

What do you want to leave us with?

I’ll leave you with this. I remember I was friends with John Baldessari, who was a mentor. He passed away last year. And one day, we were in Miami, and we were on some panel or something, and John was famous for drinking martinis, so he said, ‘Gary come sit and have a martini with me.’ So I am really excited, I am much younger and I am having a martini with John Baldessari. And we are talking and I say, ‘John I noticed in your last show that there seems to be threads of work from way back in the 70s, what’s happening there?’ And he looked at me and was like ‘wow, I can’t believe you picked that up.’ And I said, ‘well I look at everything you do.’ And he said, ‘you know, Gary, one of the things when you get to be an older artist, you are fortunate enough that you can actually go back and look at some of the things that you have done before and re-look and re-use them or continue that conversation with all the years that have passed and the work stays fresh and is within your voice.’ And I looked at him and I was like, ‘goddamn I can't wait until I get to that stage.’ And I wish he was around still so that I could say to him, ‘John, I think I finally got to the place where I can actually comment or use some of my older language in a new way.’ And I think he would be really happy to see me doing that.