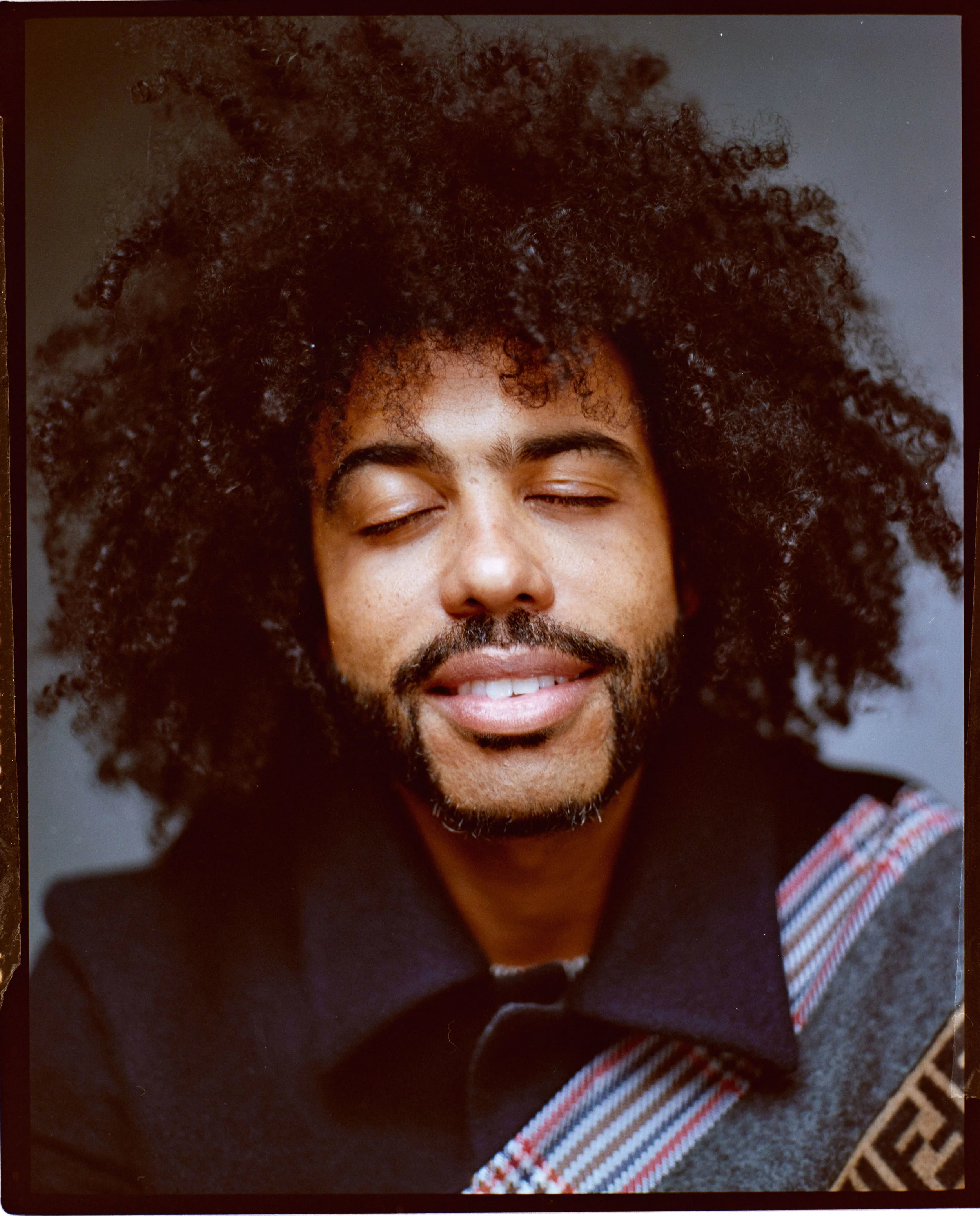

Daveed Diggs

by Flaunt Magazine

“I like a good basketball game, except when the Warriors are playing. It stresses me out to such an extreme level.”

I’m talking to 21st century Renaissance man Daveed Diggs, one day after his Golden State Warriors took a commanding 2-0 lead in the 2018 NBA Finals. Diggs can relax—he’s earned it—but relaxation doesn’t come easy for a man with so much on the stove.

Since landing both a Tony and a Grammy for his featured roles as Thomas Jefferson and Marquis de Lafayette in Hamilton, Diggs has covered more ground than Draymond Green in the Warrior’s defensive scheme. He’s notched recurring roles on both The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and Black-ish. He has future credits on Dan Gilroy’s Velvet Buzzsaw and TNT’s adaptation of Bong Joon-Ho’s Snowpiercer. He writes rhymes for a handful of hip-hop troupes, including the Sub Pop- signed clipping. He even teaches a verse seminar, entitled BARS, with Blindspotting co-star and screenwriter Rafael Casal.

I expect Diggs to appreciate witty cultural crossover as much as the next dude, but I’m surprised by the extent of his Oakland fandom. Throughout our hour-long conversation, the 36-year-old reps team and town like a proud parent, although neither now resemble the touchstones of his youth. The Warriors—like the Oakland depicted in Diggs’ screenwriting debut Blindspotting—have a complicated relationship with neighboring Silicon Valley and its notions of progress. On the one hand, the team’s beautiful brand of basketball ballet has put it on the verge of its third title in four years; on the other, the cheapest seat for Game 2 was $1200, a figure few native Oaklanders can manage.

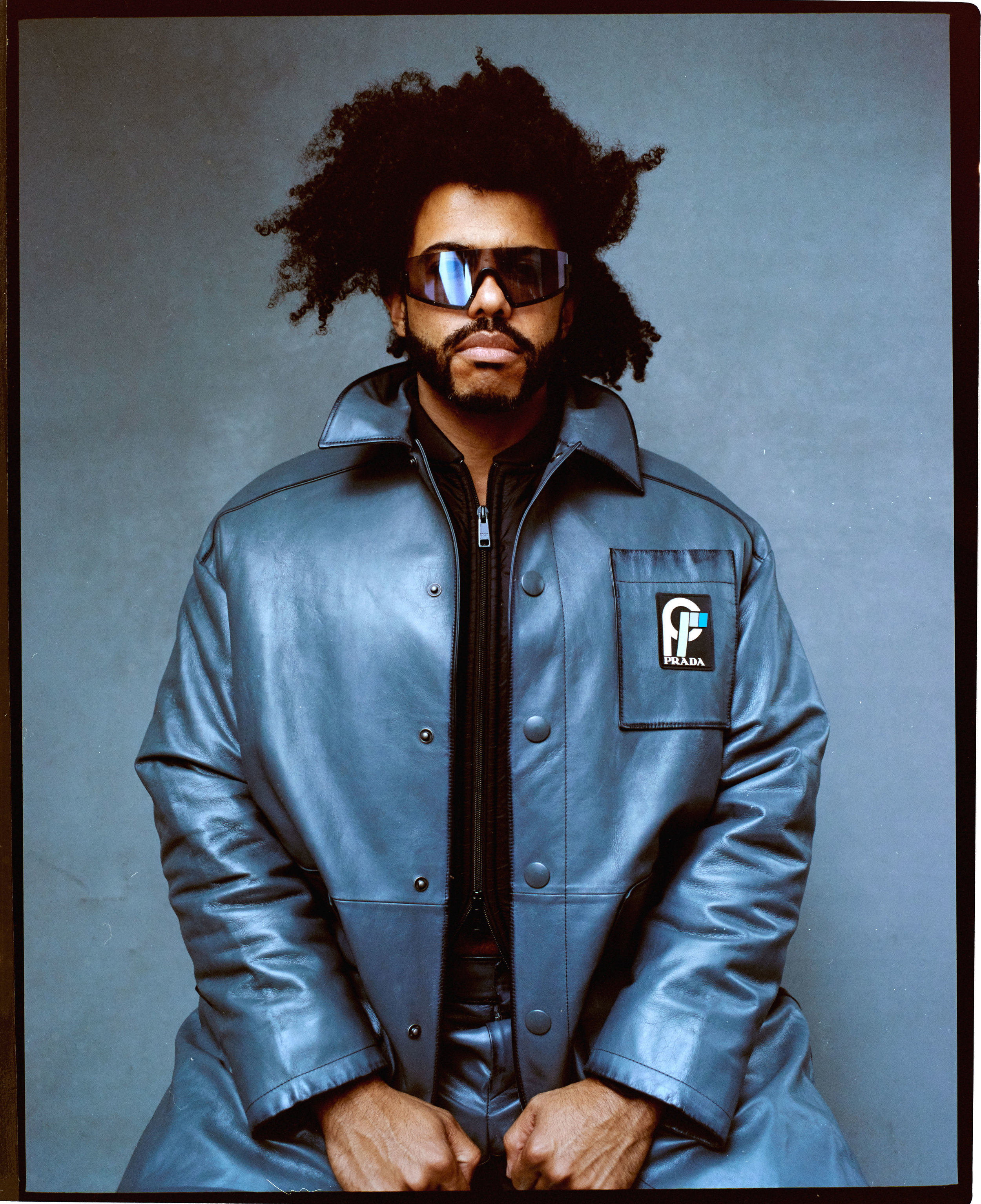

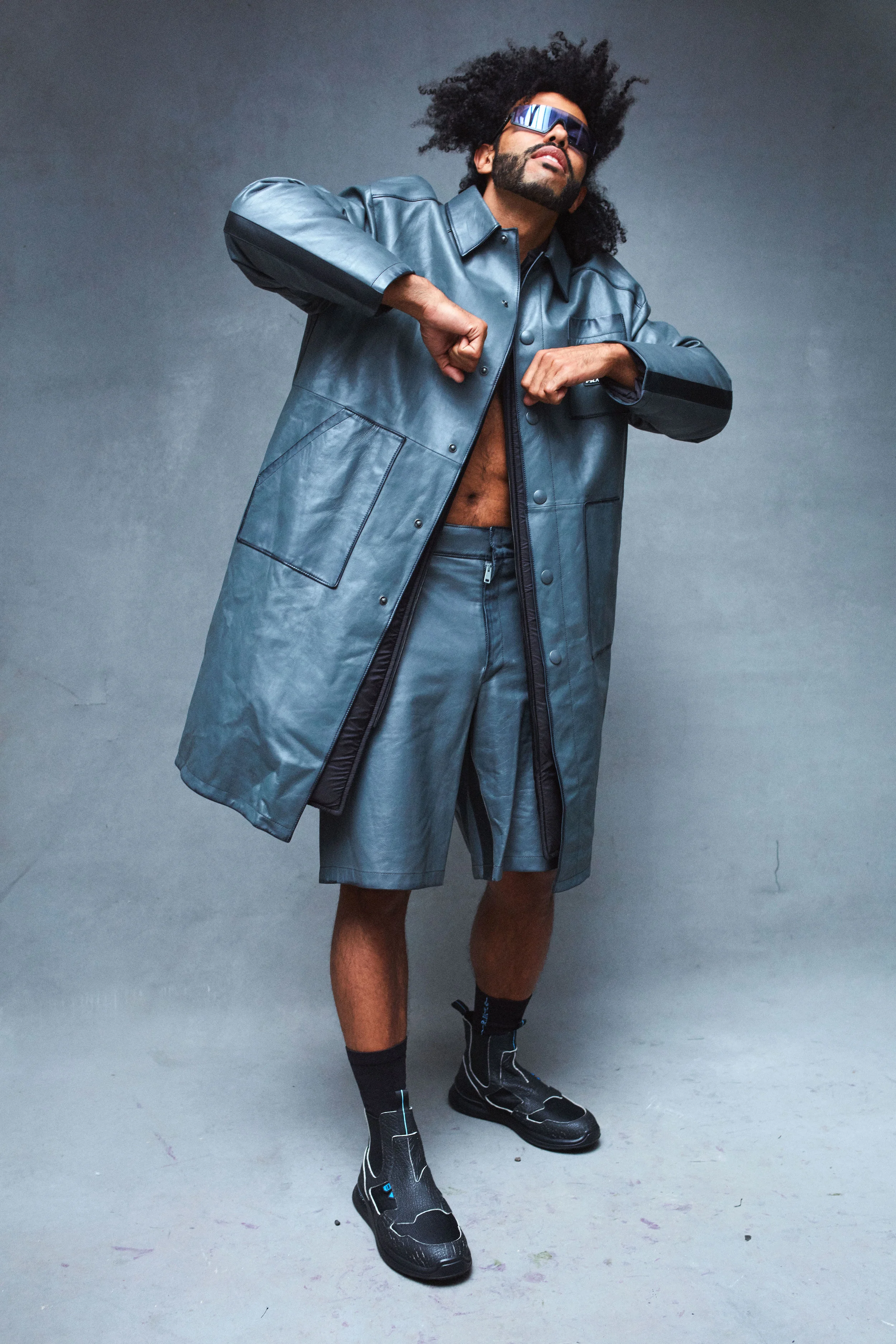

PRADA coat, shorts, and shoes and WESTWARD LEANING sunglasses.

Then there’s this: after 40 seasons of Oakland underscoring the arena’s title line, corporate tech giant Oracle purchased the rights to the Warriors home court in 2006. The team will play at the Oracle for one more season then move to the Chase Center in San Francisco’s Mission District. “It’s certainly symbolic of a thing that Oakland held very dear that is now disappearing,” Diggs says.

But rather than wallow in the loss, Diggs is doubling down on his town with Blindspotting, which portrays an Oakland fighting to preserve the old while coming to terms with the new. The film follows Diggs’ character, Colin, during his final three days of probation. He and his white, troublemaking best friend Miles (Casal) work as movers, and when Colin witnesses a white police officer gun down a black man in the street, the two men are forced to grapple with their differing identities in the rapidly-gentrifying neighborhood in which they grew up.

Like Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, Blindspotting smothers its setting in jazzy, digressive details that, taken together, paint a rich portrait of a neighborhood in transition. There’s the shapeless block nuzzled between two Victorians. There’s the Oakland tattoo Miles shares with some fuckboy. There’s Kwik Way, which now serves and caters veggie burgers. There’s the $10 green juice. There’s the gun—introduced in the first act, only to be frequently brandished in the third.

For a film charged with chaotic fits of verse and soliloquy, Blindspotting avoids becoming a finger-wagging sermon on the future ills of white-washed gentrification. Instead, these symbols situate themselves in the past, and it’s evident that my serpentine conversation with Diggs must also head there if I’m to fully appreciate how he developed such a unique, evenhanded perspective.

* * * *

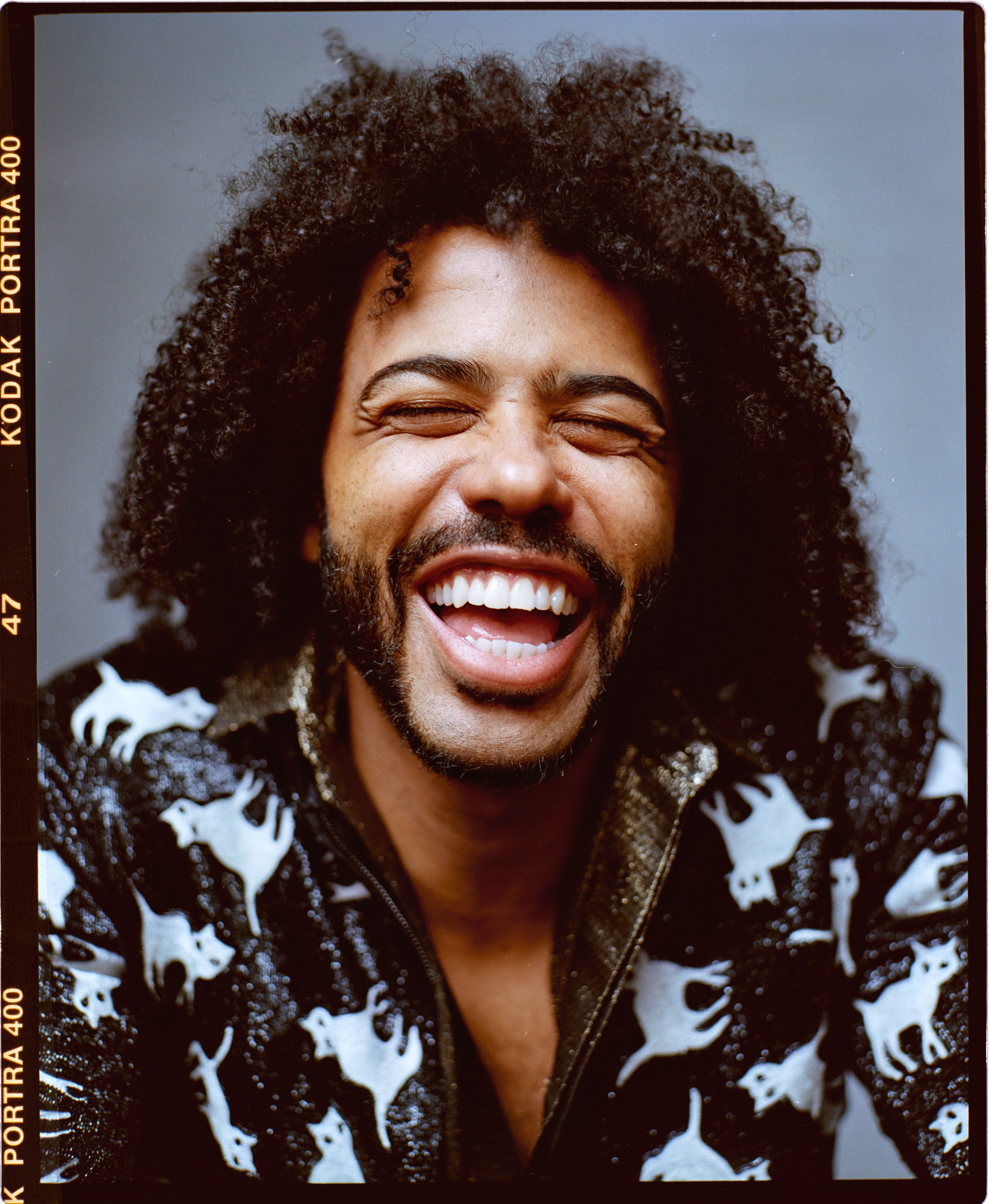

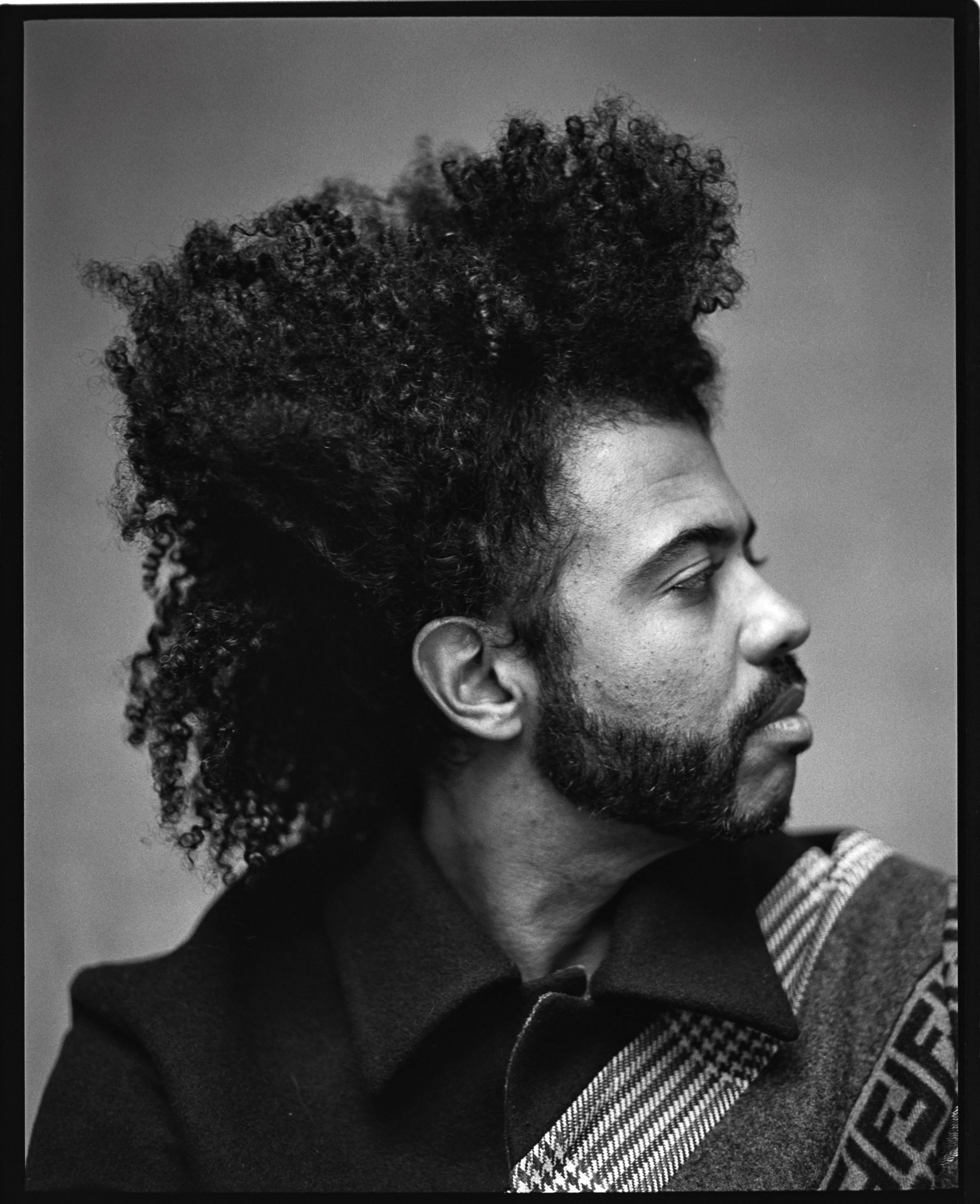

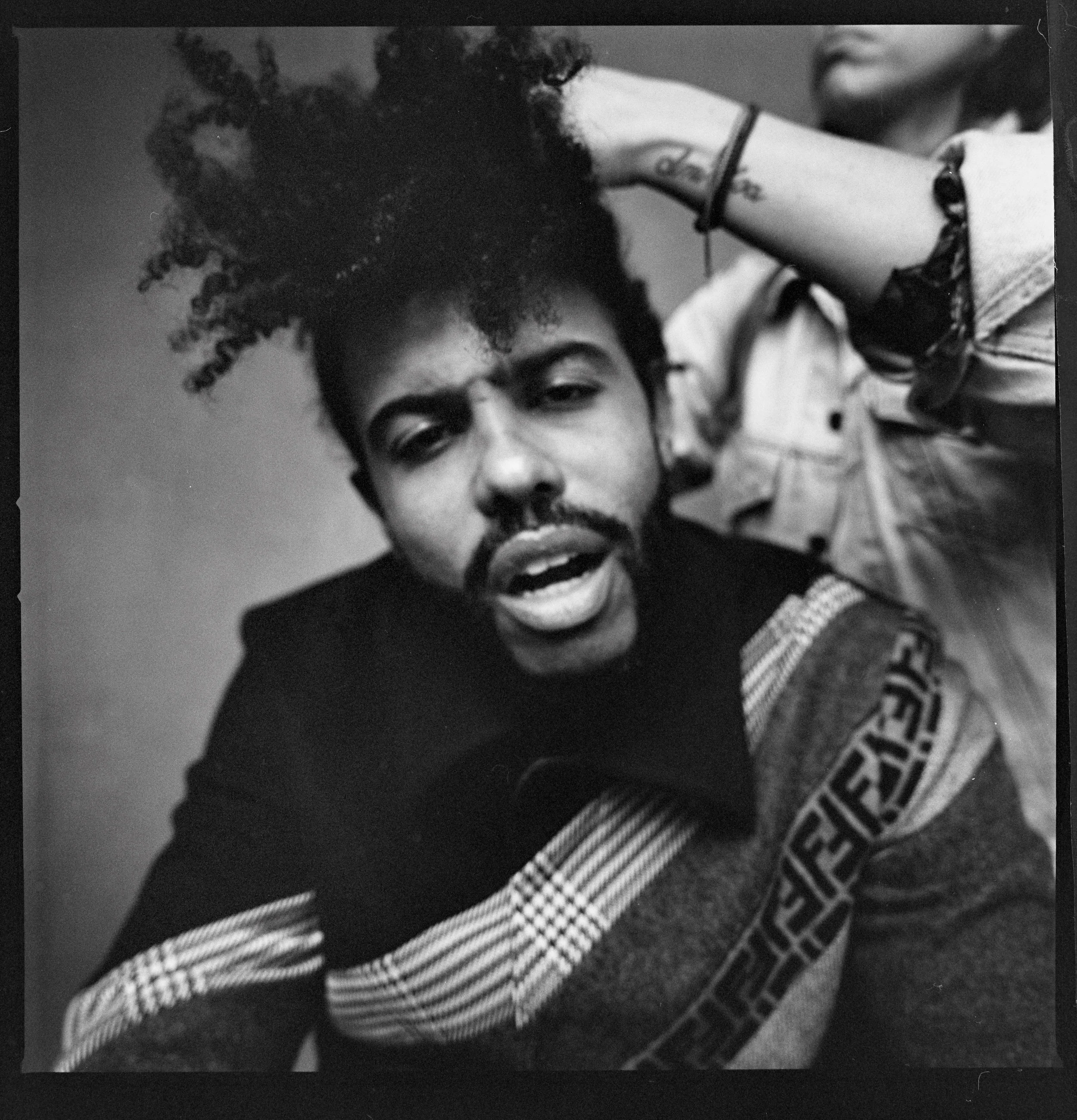

LOUIS VUITTON coat, top, t-shirt, shorts, leggings and shoes.

Born and raised on 44th and MLK, Diggs has certainly taken a circuitous path to end up writing a screenplay centered in his hometown. His mother, who’s Jewish, and his father, who’s African- American, both encouraged their son’s endeavors, even though the two separated when Diggs was young. During his Tony acceptance speech, Diggs recounted a memory from preschool in which he and his father performed a gymnastics routine—wearing matching rainbow tights—in lieu of the class’ production.

The lesson, Diggs told the audience, was: “One, my mom gave me permission to do something that everyone else wasn’t doing, and two, my dad supported me and made it possible.”

While attending Berkeley High School, Diggs continued to write his own script. He doubled as a student athlete, setting a still-standing school record in the high hurdles while simultaneously anchoring the school’s slam poetry program. Berkeley was also where Diggs met Casal. The two quickly formed a friendship based on a shared interest in verse, specifically the Bay’s hyphy movement, which was still strengthening a decade into its formation.

“I’ve been hanging with E-40 a lot,” says Diggs. It’s the one time Diggs’ fronts his fame all afternoon, even though the Hamilton cast performed several numbers for the Obamas at the White House. “Imagine being able to write a song with your all-time favorite rapper. It’s pretty crazy, probably my favorite thing I’ve been able to do.”

But it wasn’t always peaches. After Berkeley, Diggs attended Brown as a theater major, graduating in 2004 with few job prospects. He moved to New York, where he slept on subway cars, auditioned for off- broadway gigs, and tried to make his $100 in unemployment benefits last the week. It didn’t, and after moving back to Oakland, Diggs started working as a substitute teacher.

In hindsight, these thin years proved integral to Diggs’ development. They afforded him time to perfect his crafts—as both an actor and hip-hop artist—away from the limelight.

I ask him if there was ever a point when he thought about giving up the dream. “You know—make it straight, go get an MBA?”

Diggs is a minuteman, armed with responses for questions he’s answered a zillion times, but this one gets him thinking.

“The longer you commit to being an artist, it turns out the fewer skills you develop. I imagine that working a cash register would have been very hard for me... But honestly, your financial situation doesn’t ultimately determine your happiness, so you might as well just do something you like.”

* * * *

LOUIS VUITTON coat, top, t-shirt, shorts, leggings and shoes.

“I only met Lin because of a clerical error,” answers Diggs, when we make it to Hamilton.

The fairytale: fresh off a tour with his experimental rap trio clipping., Diggs was phoned into the same assignment as another substitute teacher. A fellow freestyler, the sub also happened to be friends with Hamilton-mastermind Lin-Manuel Miranda. After a few hangouts, Miranda pitched Hamilton to Diggs, who—after initially expressing resistance to the idea of a rap musical about Founding Father Alexander Hamilton (go figure)—joined on.

Nearly 700 Broadway performances and a treasure chest of awards later, it would be insufficient to characterize Diggs’ dual roles in the musical as a “big break.” Hamilton provided Diggs with the unlikely opportunity to develop his dual passions for verse and acting concurrently. On the number “Guns and Ships,” Diggs raps 19 words in three seconds, a Broadway record and a perfect encapsulation of the Adderall-addled Andre-3000-esque delivery that has become his hallmark.

With his acting acumen likewise cemented by Hamilton, Diggs has since landed a number of roles on the big screen. The roster of A-listers with whom he shares screen time continues to grow, but already includes Julia Roberts, Rene Russo, Jeff Goldblum, and even John Malkovich.

“I can’t talk about it yet,” says Diggs, “but there’s a scene with John in Velvet Buzzsaw that’s probably my favorite acting thing I’ve ever done.”

As made clear by the breakneck pace forged in the wake of his Hamilton career, Diggs has no interest in riding on the production’s coattails. He does, however, freely admit one bit of nostalgia. “Lin said this to me early-on: When you are a unicorn, you go through life looking for other unicorns. Then, when you find one, you need to latch on to that person.”

* * * *

LOUIS VUITTON coat, top, t-shirt, shorts, leggings and shoes.

In Rafael Casal, Diggs has certainly found a fellow creature of legend. A verse virtuoso in his own right (see: HBO’s Def Poetry Jam), Casal developed Blindspotting with Diggs over nine years, mostly while commuting between Los Angeles and the Bay. And while Diggs indicates that the two were mostly “acting like they knew how to write a movie,” Blindspotting uses its 95-minute runtime to introduce enough talking points for a franchise of films.

Spoilers suck, but I want to mention a few of these talking points. The first: Colin and Miles are sent to move the belongings of a middle-aged photographer, played by Wayne Knight from Seinfeld and Jurassic Park. The photographer, named Patrick, takes photos of Oak trees and superimposes them in places where they used to grow in the city. An Oakland lifer, Patrick laundry-lists the impacts of gentrification. Then he encourages the two men to drop their frames, walk towards each other, and stare. The camera focuses in on their expressions, the face of a black man, and white man, inches apart. They stand this way for about 30 seconds, before breaking out into laughter, at the expense of what they perceive to be Patrick’s new-age nonsense.

When I ask Diggs’ about the airtight scene, he has much to offer. “The scene acts like the film’s thesis. For the first time, we see somebody (Patrick) experiencing palpable despair for what’s happening to Oakland. Then we also have the intersection of race and masculinity... The only socially accepted modes of expression for men are anger and humor. We have two lifelong friends, of different races, who can’t experience an intimate moment without deflating it with laughter.”

Spoiler #2: “We took over the neighborhood liquor store on one of the first days of shooting... We’re on the street, and this white dude in hoop shorts, sandals, and tattoos is shouting into his phone, “Goddamn gentrification on a whole other level.”

Because gentrification is often painted as a black (or brown) versus white issue, Miles’ vantage point is one rarely given its due. For decades, Oakland was home to many white, lower-middle-class inhabitants. In fact, rising rents pushed not only Diggs’ black father out of town, but also his white mother.

“Every city we go, somebody is like, ‘I know a Miles,’” Diggs says when I ask him to discuss the reasoning behind the portrayal of Miles.

“You have to imagine Miles got beat up everyday for being the only white kid, so he’s built this identity on being from the neighborhood. It’s very threatening for somebody to take that away from him. Even if he doesn’t experience the same physical distress as Colin, Miles pretty much feels everything else, perhaps even more acutely.”

* * * *

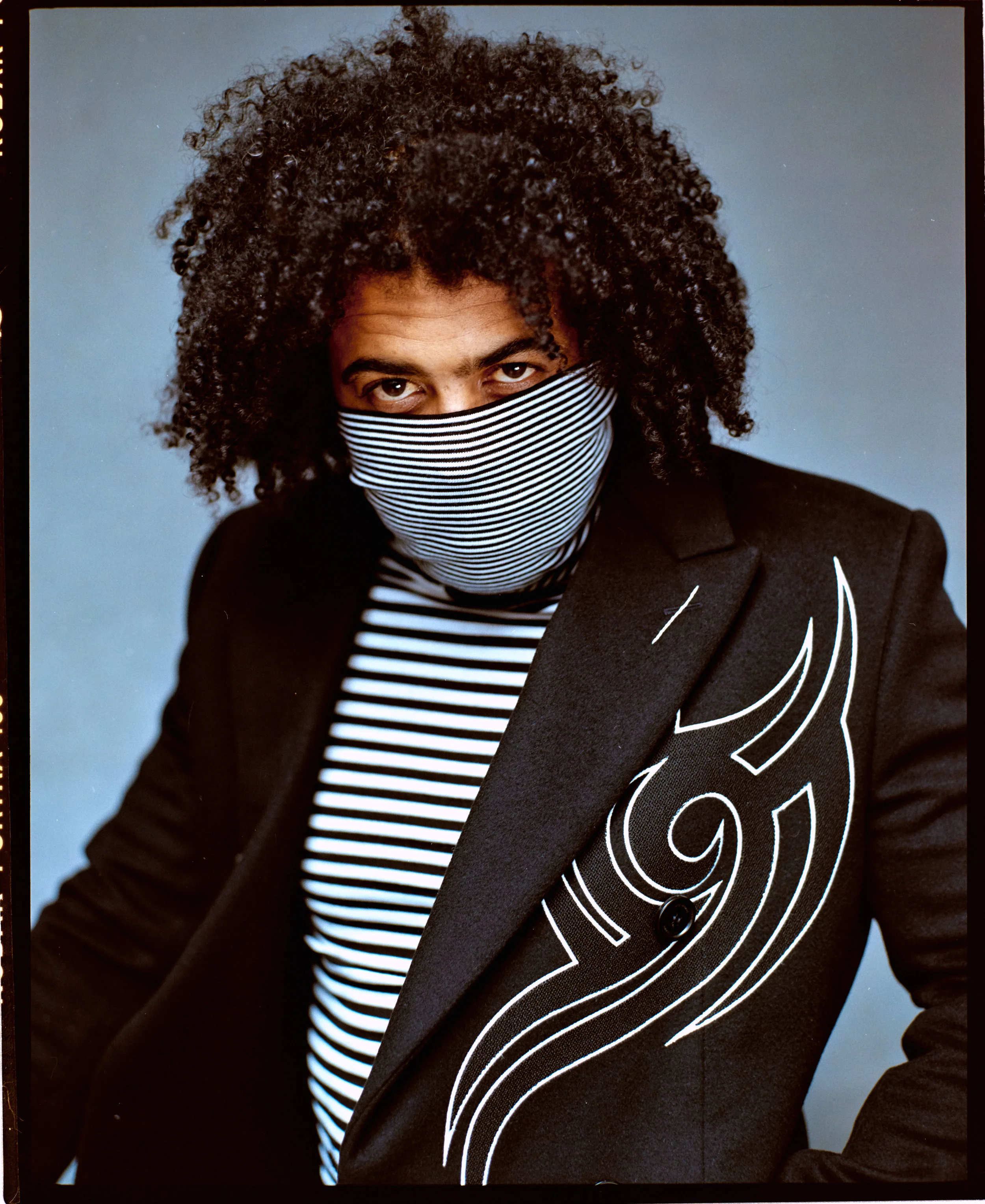

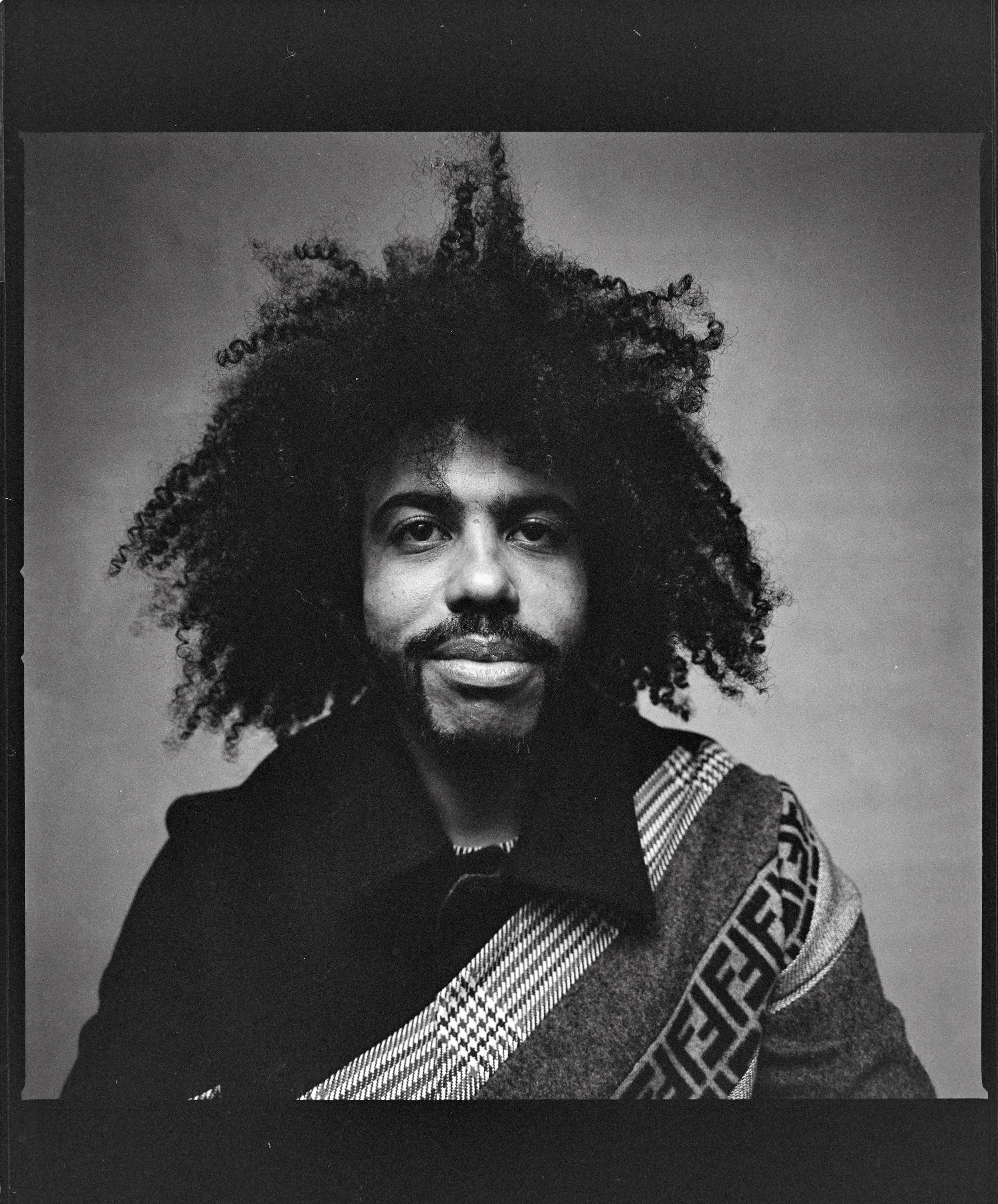

DIOR HOMME coat, turtleneck, pants and shoes.

We often forget that navigating our Rorschach blot of culture is a complicated, often visceral undertaking not only for those who hang on to its margins, but also for those on its center page. It’s a tall task, grappling with race relations, gentrification, identity, police brutality and more, all in a tidy 95 minutes. But the creators of Blindspotting aren’t trying to tell you what to think. They make only one suggestion: Look deeper.

“When you move to a new place, you have the opportunity to either acknowledge and become part of the community already there, or to pretend it doesn’t exist. That’s the choice that people have to make on their own, but of course when it’s far enough along that you can’t even recognize the culture that was there before, well, that’s a problem.”

* * * *

If there’s one difficulty in writing a feature on Diggs, it’s determining what to omit. There are enough musical projects, shows in production, and socially-conscious endeavors to fill this magazine cover to cover.

He’s a person with as many enviable talents as, say, the Golden State Warriors.

Still, as I sweat to present what’s past, now, and next for Daveed Diggs, I can’t help but feel like I’m missing something. The effect mirrors what Janina Galvankar’s character in the new film, Val, terms “blindspotting”—the idea that you can see one thing while missing something else that is a crucial part of the picture.

“You know, even though we’re losing both the Raiders and Warriors,” Diggs says as we wrap up our conversation, “I’m stoked. I can’t wait to catch some A’s games in their new stadium. I hear it’s going to be a beautiful park.”

Written by Jonathan Lipshin

Photographed by Alexei Hay

Styled by John Tan

Grooming by Jillian Halouska