Casey Affleck | Because Even the Spectacled Eider Still Needs Glasses to See

by John-Paul Pryor

HERMÈS shirt and pants and SCAROSSO shoes.

“You cannot swim for new horizons until you have courage to lose sight of the shore.”

– William Faulkner

In recent years, cinema has become increasingly defined by the desire to exploit a public fascination with the spandex-clad more-than-human—rather than look towards the more interesting vistas of human experience and emotion. In addition to this prevailing trend, only a very small handful of contemporary films dare to venture outside fantasies of consumer capitalist society and portray the complex inner lives of real working people. To paraphrase a point made by philosopher Slavoj Žižek in his recent treatise Like A Thief In Broad Daylight, the woke brigade are only too ready to claim it a travesty that a populist Hollywood vision, such as La La Land, has no LGBT+ characters represented, yet practically no one points out that it also characteristically fails to represent anything close to the lives of the millions of workers in the California gig economy. In fact, the truly monolithic tribulations that face everyday working people in their day-to-day lives, such as profound loss, bereavement, crippling financial pressure, and hard-to-heal relationships, seem to be frequently overlooked by an industry all-too-often to be found in thrall to Übermensch-driven fantasies.

The actor Casey Affleck is, then, something of an anomaly when it comes to the entertainment-driven environs of the Big Machine, having made mid-career choices that allowed him to deep-dive into some of the most torturous emotional landscapes imaginable, conveying the all-too-real struggles of common people. Affleck’s understated, nuanced yet visceral humanity has found the big screen in uncompromising films such as Manchester By The Sea, A Ghost Story and Light of My Life, and he continues to cement his reputation apace this year with the mid-pandemic release of Our Friend and The World To Come—two films set in very different eras that deal in the timeless subjects of love and loss. In these excellent offerings, by directors Gabriela Cowperthwaite and Mona Fastvold, respectively, Affleck plays both a 21st century working man who loses his wife to cancer, and a 19th century working man who loses his wife to love. Suffice it to say, the quiet dignity he brings to both of these decidedly human roles—poles apart in historical context—is nothing short of masterful.

“I recently heard this ornithologist say that the work of being fully yourself is the work of an entire lifetime,” Affleck will later tell me, deep into our interview, as we unpack one’s potential purpose amidst life’s ceaseless evolutions, “And that you constantly have to be doing that work. He wrote a great book called Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, and spent his whole life studying birds. He’s just so observant, calm, patient, and appreciative of things that have nothing to do with him—there’s a quality to him that is so antithetical to the me-me-me pace of our modern lives.” Affleck’s openness to appreciation as a guiding light will resonate with me long after our conversation, and yet it’s this precise yet gentle unfolding of character that’s consistently evidenced in role after role he assumes. The unique less-is-more talent Affleck has on-screen in conveying emotion is perhaps matched only by an infamous real-life reticence for in-depth discussion of his craft, or indeed anything that could be seen to border upon the pretentious.

FENDI coat and pants, TEDDY VONRANSON sweater, and JIMMY CHOO boots.

CANALI top.

Both of these new films could obviously provide ample material for a feature—Our Friend being based upon the real-life experience of Esquire writer Matthew Teague, and the Ibsen-esque The World To Come, which Affleck co-produced, dealing in the societal constrictions of an antiquated patriarchy. However, I can’t but help to consider my invitation to interview him at a truly unique moment in cultural history for The Dawn Chorus Issue, as an opportunity to try and gauge his thoughts on some of the big questions of our era. In fact, as I hit him up across the digital stratosphere from lockdown in London, there seems to be no better place to begin than the existential challenges of our unabated global pandemic. I mean, where in the hell else are you going to begin any conversation right now?

“I’m okay,” says the actor with a smile while rubbing tired morning eyes, when I ask him how he has been bearing up. “I mean, no one in this house has gotten sick, thankfully, and I worked so much last year that I was able to spend a year not working, which is a real luxury, so it’s all right—the kids are a little bit stir-crazy from not going to school.” Affleck is father to two young children, and has, in recent years, become somewhat synonymous with portraying parenthood onscreen—not least in his latest two offerings, in which he plays opposite heart-breaking performances from on-screen partners Dakota Johnson and Katherine Waterston, respectively. I suggest to him that, in a general sense, it’s fair to say that we are yet to discover the effect ubiquitous lockdowns have had on the younger generation. “It’s difficult for everyone,” he agrees. “But when you are a teenager, the chemistry in your head is already so crazy, and all you really want to do is socialize. To be cut off from all of that just seems like a recipe for disaster in terms of anxiety and depression. I don’t know what those statistics are, or if there’s people measuring it all somehow, but it must be through the roof.”

I suggest it’s certainly been a difficult time in terms of being creatively inspired, having struggled myself with the internalized pressure that tells you this is exactly the right moment for you to pen the next Infinite Jest or Finnegans Wake. “Yeah. I’ve done nothing,” says Affleck in agreement. “If you look at social media, then it seems like everyone is learning instruments and baking bread and gardening, and doing a million things. But I’m like, I just stare at the wall…” I ask if he is one of those people that subscribe to the notion of radical social change and a more empathetic world post-lockdown? “Who knows what’s going to happen on the other side of it? I don’t see an immediate sign of that, of a more empathetic society when I look around,” he pauses—it’s the first of many in our interview, and it’s clear he is a person who thinks carefully before he speaks. “I guess every time that there has been some big disruption, like the Industrial Revolution, or whatever, it takes people about a generation to settle into it. It is kind of de-stabilizing, and the technology has also made us all a little bit crazy, you know?”

It’s a salient point in an era that is best defined as one of accelerated exponential growth in technological newness. “There is also this phenomenon of toxic misinformation, and that is very real, but I don’t know what can be done about it,” he continues. “What do you think?” The actor deftly flips the role of interviewee, and I suggest that it seems to me like it could very well end up splitting the world right down the middle in terms of those who believe in fact and those who believe in fiction, not that it will matter as none of us will be paying attention to much of anything beyond our feedback loops. “Completely. I mean, attention has become the new commodity,” Affleck agrees. “These devices are designed to take your attention from you, and, at the end of the day, it can just feel awful—especially if you’re unaware of all these algorithms understanding what it is that you click on, and feeding you more of that stuff. I think it’s pretty bad for all of us,” he continues. “It took what seems like a hundred years for anyone to say that the cigarette companies were preying on our lives for profit—when are they going to say that about these devices?” I suggest that there is not only the personal cost to one’s mental health in addiction to the ubiquitous smartphone to consider, but also the geo-political impact of the above-noted glut of disinformation it readily offers, perhaps best personified by the failed insurrection on Capitol Hill.

“There are a lot of things that I wish were different, but, you know, these are just the challenges of our time,” says Affleck in response. “We’ve been through a very rough patch, but I do think that we’re healing. I’m just sad that, you know, my kids have to sort of live through such constant vitriol on the airways…” Again, he pauses, before collecting his thoughts. “I think that this time will be remembered as one when really great things happen and big painful changes take place—ultimately, for the better,” he continues. “An incoming tide of change is arriving on shore, and to believe it came out of nowhere is just to say that you never looked out to sea; that you don’t know what happens at the beach. My children’s generation seems poised to be great change makers, and I hope they do it with kindness and gentle grace. In the meantime, I hope we can reign in runaway greed, and leave them with a good foundation from which to build something new. I grew up in a world that was very much like my parents’ world, but this generation has totally different ideas about everything, you know? They’ve grown up their whole lives with the phenomenon of mass school shootings, for example. I think for that reason this will be the generation that changes gun laws.”

LOUIS VUITTON jacket and pants.

There is no question that we are living in interesting times, and I suggest to the actor that one of the many things Generation Z has certainly upended with vigor is any traditional notion of masculinity. “It’s amazing,” says Affleck in agreement. “They have grown up where gender fluidity is a totally normal thing, which is wonderful.” So, what does he think these tectonic societal changes might portend for the future of the film industry? “I think there are going to be more stories being told, and that’s going to enrich all of our lives and make the industry better. Instead of it being the same point of view over and over, which is incredibly tedious, we are going to be getting much greater diversity of world views, and that’s going to make for better stories.”

It’s a hopeful enough vision, certainly. Still, I can’t help but wonder if there is another side to millennial verve that could concurrently cancel certain viewpoints onscreen if they are not deemed to fit within strictly defined parameters of the quote-unquote correct moral high ground. “It’s so dangerous answering these kinds of questions,” says Affleck, with a sigh. “I do think that the best kinds of art provokes thought and stirs feeling, and you should be able to sort of depend on society to be able to take those things in responsibly. I mean, I don’t know any people that aren’t flawed,” he continues. “I can’t even imagine a story that works where you have characters that don’t feel trapped for having made mistakes, and don’t feel like failures, in some way—that wouldn’t even be a story of human beings, you know what I’m saying? There wouldn’t be anything to tell.”

It’s certainly true that Affleck has never been drawn to the kind of characters that fit easily into classic notions of the hero’s journey. His latest incarnations are no exception. In Our Friend, Affleck embodies a man trying to deal with the imminent loss of his wife, and mother to his children, while also being aware of infidelity on her part. The process sees him express the tortuous, multi-faceted journey of bereavement (with sterling support from Jason Segel, who plays the big-hearted out-of-work ‘friend’ of the film’s title). Similarly, in The World To Come his character deals with trying to overcome the loss of his infant child, as well as the romantic love of his wife to a woman from a neighboring farm (played by Vanessa Kirby) with a noble dignity that is nothing short of profound—“He’s a man of his time, but he’s not stuck in a limited point of view,” says Affleck of his modest role in the film, which centers around the forbidden lesbian love affair of its two female protagonists. It’s precisely his ability to transmit these difficult yet universal paradoxes of the human condition that make him such a fascinating actor, more-than-worthy of his Oscar five years ago for Manchester By The Sea. But ask him about his acting process expecting any flights of fancy, and you might be disappointed: “I wish I had something brilliant to say about some Daniel Day-Lewis kind of method, but I just read the thing over and over and over, and I try to imagine what my character is feeling, and whether or not I can sort of relate to it.”

Interestingly, many of his earlier career character choices, which first brought him to the attention of a wider audience, such as The Killer Inside Me and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (written by Affleck’s friend Ron Hansen, who also co-wrote the screenplay for The World To Come with the author of the original short story, Jim Shepard) were notable in their near-pitch-black darkness. It somewhat begs the question whether in recent years he has made a conscious decision to turn away from darker roles? “I think so. When I was as a younger person, I was sort of more interested in darker material, and then I had kids, and I guess it softened a bit,” he explains. “I also started thinking a little bit more about the kind of things I wanted to put in the world. I just thought, well, there’s a place for those movies, but maybe I don’t want to be a part of it anymore,” he takes a moment, deep in thought. “I guess another piece of that is that when you put a lot into a job, it puts something back into you,” he continues. “I started to understand that more, and I didn’t want to carry around those kind of things anymore. I was more drawn to things that, if not exactly light, have a more positive spirit to them. I think you come to a point in life when you want to put something into the world that it feels like it’s you. Whether it’s good or bad, you can look at it and say that feels like me—that feels like the things I care about; that feels like how I see the world.”

SALVATORE FERRAGAMO jacket, top, and pants.

TEDDY VONRANSON sweatshirt.

TEDDY VONRANSON sweatshirt.

TEDDY VONRANSON sweatshirt.

TEDDY VONRANSON sweatshirt.

TEDDY VONRANSON sweatshirt.

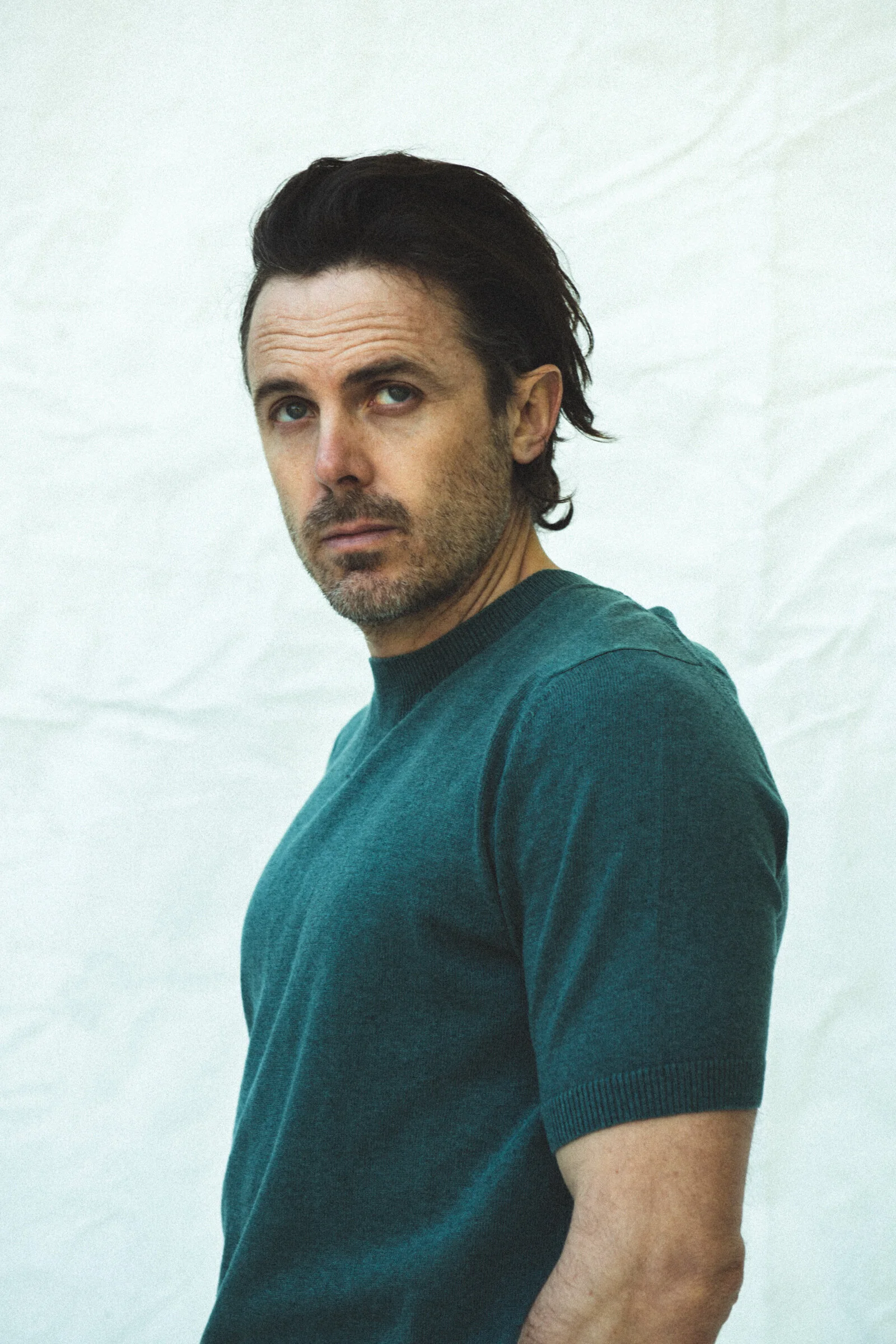

CANALI top.

It is often said that the middle years of our life provide a vantage point of looking backwards as much as forward, and I wonder how Affleck, now 45 years old, feels in terms of the choices he has made in a 25-year career, and what his next steps might be. “In the last five years or so, it has felt like there’s been sort of an organic emergence of a kind of curiosity about other things, with some new urgency,” he says. “It can feel like there’s an hour-and-a-half start to explore some new territory, and with the world paused like it is, it feels like a good place to take a beat and evaluate what are some of the other possibilities I’m interested in, or might like to pursue. I don’t have anything planned to direct right now, but I would love to direct more. I really like it,” he continues. “I don’t know. I’ve discovered, maybe too late in life, how great it feels to be selflessly of service to other things, other ideas, and other people.”

This all sounds like a process of self-actualization, and I wonder what his thoughts are on the journey to becoming the best version of one’s self. Given his passion for the aforementioned book by the ornithologist, Professor J Drew Lanham, I can’t help but wonder whether there is a spiritual dimension to Affleck—if there is something he believes about life and death along theological lines. “Man, you ask some real zingers,” he says with a smile. “I had no religious or spiritual instruction as a young person. I learned as I went. I learned faith through the experience of life—of being hit by cars that were driving on the sidewalk, of sitting silently and alone in dark and painful places, of feeling the warm light of love on my face, of seeing my children born and grow, and seeing people I loved and believed indestructible die,” he pauses, and I feel inclined to ask him how he taps into the grief he portrays with such coruscating authenticity on screen. “Well, I don’t believe that there is any one kind of process of grief, and I don’t believe that there’s always a purpose to suffering in a way that some people do,” he says. “I think sometimes there’s just a season of suffering, and you can make it something that you want it to be, but it isn’t inherently purposeful. I mean, you can create some purpose for yourself, but there is never going to be a time when there isn’t suffering—there’s never going to be a sort of pretty spot on the horizon where all the problems are solved.”

I suggest that this notion of there being no definable horizon point could also be a reasonable analogy for the multiple paroxysms that are currently shaking the political landscape in America. “Yeah. Democracy is messy. It’s not always pretty, and the outcome of democracy can feel disappointing,” says Affleck. “But that is okay because democracy itself is a wonderful thing, and its virtue shouldn’t be measured by the outcome. I think progress happens slowly, it never happens overnight—I mean, a lot has changed in the last couple of generations.” Given this sense that everything is essentially a work-in-progress, does he have optimism for the future? “Yeah, sure. It’s a really exciting time, man. I mean, sometimes it’s confusing and sometimes it’s painful, and it’s definitely not always pleasant, but there are opportunities to grow and make change in your own life and in the world around you. Despite all the pervasive anxieties that can come along with technology, and all the tentacles of that, there is still something really wonderful about the newness of right now.”

It feels like a positive note on which to end our conversation. However, given the actor’s penchant for playing the workingclass everyman, I am keen to press him on what he thinks are the characteristics of the much-touted soul of America that the country’s new premier claims to be battling for. “I think we like to redefine ourselves,” he says. “We keep track of our past and original destination, but we change course boldly, and sometimes we even change the name on the side of the ship. We have some problems, but there are always some of us who have the courage to face them, name them, and lead us to change them.” And how might this sentiment of review and redefinition relate to his own life, I wonder, asking him one of my favorite questions from the Proust playbook—what do you consider to be your greatest achievement? “It’s just not giving up, and managing to keep going, despite all the failures, the constant unemployment, the movies that suck, the things that people say… everything, all of it. You just learn to, like, plow ahead,” he says, with a final pause, and an incoming call on his cell, which he swiftly silences. “I guess it’s just kind of about enduring and moving forward, something between stoicism and Buddhism,” he says, laughing suddenly. “I don’t know. I’m neither a Buddhist nor a Stoic. I might like what I found in the schools of Herman Hesse and Dr. Seuss, but I don’t know anything, really, and my practice is weak—there is more in a chapter by Thich Nhat Hanh than I could say in a day.” Perhaps there is indeed, but as I wave goodbye through the screen to an actor who is so uniquely adept at portraying the dignified endurance of the common man, I have to admit, I’m not so sure.

KING & TUCKFIELD sweater and BRUNELLO CUCINELLI pants.

Photographer: Ian Morrison

Stylist: Monty Jackson

Groomer: Barbara Guillaume

Flaunt Film: Mason DePaco

Text: John-Paul Pryor