Blueprints of the Unfortunate

by Sway Benns

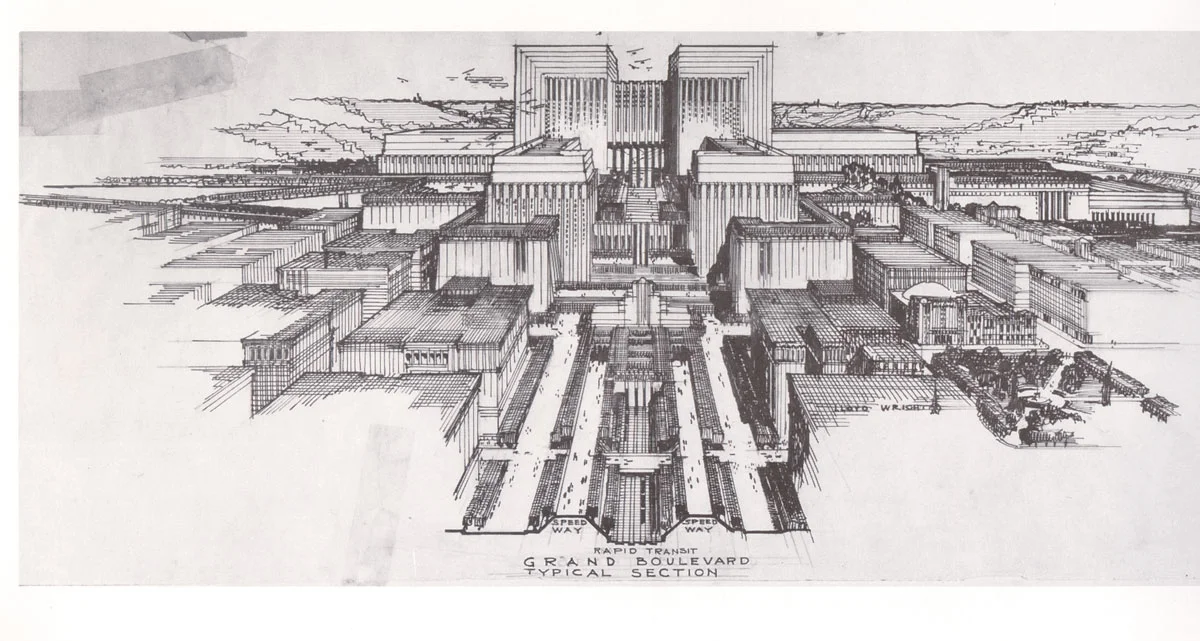

Frank Lloyd Wright, Los Angeles Civic Center, view from south along Grand Avenue, Los Angeles CA. FROM NEVER BUILT: LOS ANGELES.

Heinrich-Hertz-Turm. Hamburg, Germany. Architect: Fritz Trautwein, 1968-2001. Closed due to asbestos. Photo: Matthias Heiderich.

Burj Khalifa. Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Architect: Adrian Smith. 2010. Dubbed the “Word’s vainest building” by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat in 2013. Photo: Matthias Heiderich.

UAE SKYLINE AND UAE CONSTRUCTION SITE Photo: Matthias Heiderich.

Helical walkway encircles 1,290-foot tower. FROM NEVER BUILT: LOS ANGELES.

Map of Gulliver’s Kingdom. Yamanashi, Japan. Architect: Juergen Specht. 1997-2001. Borders the Aum Shinrikyo cult’s former nerve gas production facility and the Aokigahara Forest, reportedly the most popular place for suicides in Japan. Photo: Mandias.

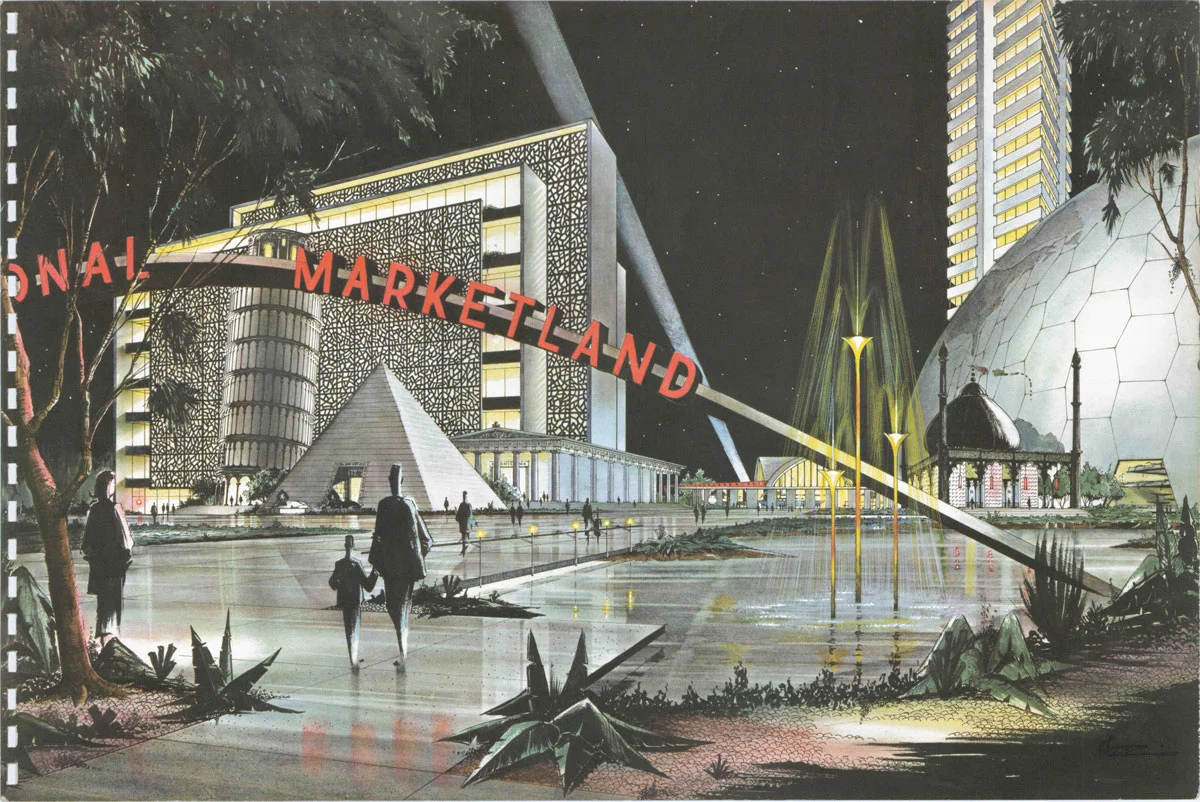

Entryway reveals replicas of architectural monuments. from around the world FROM NEVER BUILT: LOS ANGELES.

Meso-American palette for walls, pediments, corbels, and friezes. FROM NEVER BUILT: LOS ANGELES.

Blueprints of the Unfortunate

Live From the Surface of the Earth

The Lotus Riverside building collapse in Shanghai in 2009 was a clear failure, managing to leave unfulfilled one of the basic tenets of good architectural design: remaining upright.

But, typically, the success—or failure—of a structure is not so clear-cut. A building doesn’t always fail because it falls. The potential for implosion, literal or otherwise, is everywhere. To wit: Is the building energy efficient, functional, accessible? Is it beautiful? Will it exceed its contemporaries? Will it impress? Figures are calculated; flaws are weighed on imperceptible scales. In some cases, debates rage, a last word unattainable as the function of the space perpetually evolves.

A case in point: The architects of Dubai—hell-bent on creating an enviable cityscape with recently acquired wealth—stacked cinderblocks and plexiglass with wild abandon, pausing only to rub together their steadily drying oil-greased palms—only to learn that the whole plan is a bit shit. The Burj Khalifa still stands, a glass and steel mirage, an architectural feat, and yet, it’s imposing, too expensive, near empty, and socially irresponsible (so say its detractors). It’s clear: A lack of tact—a minutia’s worth, or a mile—and suddenly your engineered aspirations are demolished by a collective conscience synced in its cruelty.

As with any profession, those content to plod along will mostly do so unscathed. The architectural landscapers, for example, fiddling around with the placement of succulents, rarely risk uproars of disapproval from their constituents, a comfort in a world where our failures mark us. So why would impermanent beings attempt to create objects of near permanence (pending fire, flood, or act of God)? Their critics face little incentive, biologically, to bathe an imposing edifice in a flattering light—and yet architects maintain some of the lowest rates of depression amongst various collared industries. They continue to earn their keep, altering the landscape of the surface of the earth, creating spaces for utility and amusement, long after the calls for praise (or displeasure) have dulled. And displeasure seems inevitable within the scope of the work. Even veteran Frank Gehry stumbled, his Walt Disney Concert Hall nearly blinding pedestrians with its shiny veneer and inopportune angle for the sun; its surface had to be rebuffed, a fix that cost near $90,000. And the universe itself, wondrous in its construction, possesses a few minor faults—Reno being a notable example.

Never Built: Los Angeles, an exhibit at the Architecture and Design Museum, Los Angeles (on view through October) delves into this great fascination, and failure, to build.

The exhibit, named after a book of the same title (Metropolis Books, July 2013) and curated by architectural journalists Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin, presents failure as a false start. Never Built scrutinizes an aborted metropolis, bureaucratic red tape encumbering proposals for monorail systems, civic centers, and helical walkways—many with designs seen as monumentally progressive in city planning and environmental achievements (and several of which are featured herein). The plans—including Horace Dobbins’ California Cycleway, a proposed elevated bicycle path—languished in the hands of an uncooperative city government and the rumored lure of big money from the automotive industry. (An industry that would virtually implode soon after the construction dust of the 101, the 110, the 405, the Five, and the Two had settled.)

So, how do we know these structures, whose lifespans often far surpass those who make use of them, will be deemed failures when all is done and dusted? It’s fair to wonder if some ancient Egyptians simply saw the pyramids as eyesores. Perhaps one day, the Heinrich-Hertz-Turm will spin again, and residents of Hamburg will enjoy the view of their city in the rotating capsule, free from its current looming threat of asbestos. Though, in defense of those architectural naysayers, one does wonder: Why the fuck would you build a theme park bordering the site of Aum Shinrikyo’s former chemical weapons manufacturing plant and Aokigahara Forest, the most popular place for suicides in Japan? It’s impossible to know. Unless you’re the architect.

Photography: Matthias Heiderich at Matthias-Heiderich.de and Mandias at OldCreeper.com. Illustrations from Never Built: Los Angeles, Metropolis Books.