Andrew Garfield: Breathing Life into Characters on the Page

by Flaunt Staff

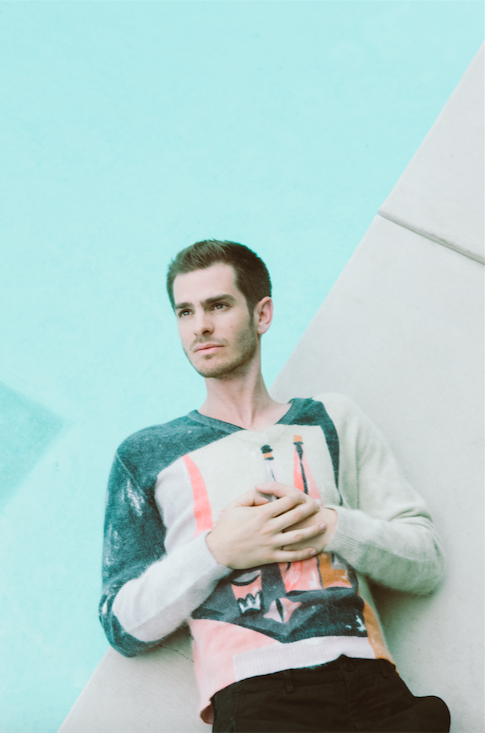

Andrew Garfield | all images shot by Eliot Lee Hazel | FASHION CREDITS: DIOR HOMME turtleneck and keychain, HAIDER ACKERMANN pants available at MatchesFashion.com, and LOUIS VUITTON belt.

Autumnally dressed in a long black woollen coat and scarf, Andrew Garfield greets me enthusiastically in the middle of a large hotel restaurant. It’s the day before his latest film, Breathe, is due to open the 61st BFI London Film Festival, and he’s in the middle of a promotional hurricane that will see him travel between London, Zurich, New York and Los Angeles in the space of a few days. Unsurprisingly, after a year which has seen him take on four of the most demanding roles of his career, he’s looking tired. Garfield spots a comfy sofa away from the bustle of the restaurant and suggests we sit there. He looks relieved to sit down.

After placing my tape recorder between us on the sofa, it’s not long before Garfield starts to inspect it. He picks it up, pulls it close to his face and checks to see if it is working by talking into it loudly. “Is that going to do it?” he inquires, intently examining the screen. I explain it’s working and that I’ve also got a back-up one in case of any issues; he starts to comically scrutinize that one too. “It’s okay, if it fails I’ll just do it all again and repeat everything word for word,” he deadpans, a mischievous grin on his lips.

Meticulous attention to detail has always been at the heart of everything Garfield has done. The Pope recently joked that Garfield had prepared so well for his role as a Jesuit Priest in Martin Scorsese’s Silence that he deserved to be ordained. Not only did he fast for long periods, attend isolated spiritual retreats and endure week-long self-enforced silences, he even spent an entire year studying Jesuit spirituality. Treading a delicate line between the conscientious and the neurotic, Garfield is someone who wants to get it right.

BURBERRY shirt, 3.1, PHILLIP LIM pants, and ANONYMOUS ISM socks.

He is also unafraid to play challenging or sensitive roles, having portrayed everyone from a child killer in Boy A to a conscientious objector in Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge; a gay man battling AIDS in Tony Kushner’s play Angels in America, to a paralyzed disability rights campaigner in Breathe. “It was a very specific challenge,” Garfield tells me about his latest role. “I don’t know about comparing it to anything else I’ve done but it definitely had its own challenges. It was an amazing role to prepare for really, to get to know this incredible man through his wife, through his son, through his grandchildren.”

In Breathe, based on a true story, Garfield plays Robin Cavendish, a man who was left severely paralyzed after contracting polio at age 28. An athletic man with a love of adventure, his new, pregnant wife (played by Claire Foy) is told he won’t leave the hospital and has only months to live. Permanently attached to a respirator, Cavendish descends into a crippling depression.

“There was the technical side to prepare for,” Garfield explains, “which was the disability itself and what it means for the body, what it means for the voice and what it means in terms of being breathed for by an external machine. That was the thing I was most neurotic about because it was so hard to get right—and you need to get it right. It was very hard to pin down what the sound was. Because of the nature of the disability, every single breath had to be the same. You don’t get to play with the power of your voice; to convey what you mean and feel is therefore a real challenge.”

ALEXANDER MCCQUEEN shirt and GUCCI pants.

After the birth of Cavendish’s son, Jonathan—also the film’s producer—Cavendish’s wife, Diana, learns how to work his respirator and breaks him out of hospital. Defying the medical professionals and a society entirely unequipped to support him (this was the late 1950’s), she enlists the help of their family and friends who adapt Cavendish’s home and care for him daily. Teddy Hall, an Oxford professor and Cavendish’s close friend, designs a wheelchair that holds his breathing equipment, enabling him to venture outside of his room; their pioneering work is still influencing disability aids to this day.

“I think the main thing that was reassuring was the fact that Jonathan Cavendish, Robin’s real-life son, was our producer and on set every day,” Garfield tells me. “If anything was wrong, it fell to him. It leaves myself and Claire [Foy] and all the other actors quite free to do then what we instinctively feel and trust that he’s going to guide us.”

Refusing to accept a life of limitations, Cavendish campaigned for disabled individuals to receive dignified care that would bring them a better life, and not one confined to a hospital, hidden away from society. Living a long and full life, his stalwart determinism and humor in the face of adversity served as an inspiration for many, not least Garfield.

“It was great speaking to his old friends who were just so happy to speak about him. His humor was incredible, a necessary attribute for those kinds of experiences. The British are very good at laughing through terrible tragedy. It’s an absolute necessity.”

“This film was very joyful actually because of Claire and the rest of the company and Andy Serkis [the film’s director] and especially because of the magic of Diana and Robin themselves. We were following their lead and Jonathan as a vessel as well—he definitely feels like his father’s son. He’s got a similar ability to create joy and community. There was something very beautiful about that.”

DRIES VAN NOTEN coat and RAF SIMONS t-shirt available at MatchesFashion.com.

For someone who prepares for roles so painstakingly, it is perhaps unsurprising to learn that it’s Garfield’s favorite part of the entire cinematic process. “I love it. There’s no pressure and you’re just seeping yourself in information and attempting to absorb it all by osmosis,” he says, lighting up.

“I did actually watch a lot of films that have dealt with similar, if not the same, circumstance,” he elaborates further. “Of course, My Left Foot is an amazing performance from Daniel Day-Lewis, and I also looked closely at The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, not for performance but actually for insight into that experience, that feeling of being locked-in like Robin was. I actually thought the film captured that quite powerfully. I found it difficult to watch and I think that’s a good sign.”

From the very beginning of his career, Garfield has always seemed to favor playing marginalized characters on the fringes of society. We discuss his first theatre role 13 years ago, and I explain that I saw him at Manchester’s Royal Exchange Theatre where he played the lead role as Billy Casper in Kes. “Oh no way? That’s so cool!” he booms, the performance clearly eliciting fond memories for him. Just 21 and newly graduated from The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, the performance earned Garfield numerous awards. Does he still see such roles as his artistic purpose of sorts?

“There’s definitely something to that. I’m definitely drawn to those roles and always have been. Those have had the greatest impact on me when I was young and I think they’re the ones where I feel most meaningfully invested I suppose. It’s just what I instinctively feel I’m meant to be doing.”

HERMÈS suit and NEIL BARRETT sweater available at Matchesfashion.com.

Garfield is a thinker—someone who ponders questions profoundly, often furrowing his bushy eyebrows in deep thought before (and during) his responses. “I think we all have something to give,” he continues. “We all have some meaning to add to the world and for whatever reason those are the things that have called to me.”

“It’s interesting because I’ve never really played someone from the upper classes before; I’ve never done that apart from with this particular project.” As someone from the middle classes with a very Standard English accent, this sometimes feels like a curious paradox. Yet Garfield himself clearly identifies with people elsewhere. “I haven’t really been interested before I guess because there’s something about people struggling to become who they are which interests me.”

PRADA sweater and LANVIN pants.

In playing the characters he has, one of the issues Garfield has faced is criticism from campaigners who feel the roles should be played by actors from minority groups, increasing diversity and representation in the industry. With so much attention to detail in his preparation, does such criticism sting a little, and is it valid?

“I think it’s a worthy conversation that I want to be a part of. I’m very curious about it. In Breathe, they had to cast an able-bodied actor that could play disabled because you start off with Robin as able-bodied. In terms of playing someone whose sexuality or sexual orientation I don’t share, that’s another really interesting conversation.” In Angels in America, Garfield played a gay man suffering with AIDS, and he was recently cast as a transgender female in Arcade Fire’s video for “We Exist.”

"TO BE NOBODY BUT YOURSELF IN A WORLD WHICH IS DOING ITS BEST, NIGHT AND DAY, TO MAKE YOU EVERYBODY ELSE, MEANS TO FIGHT THE HARDEST BATTLE ANY HUMAN BEING CAN FIGHT." - E.E. CUMMINGS

“I thought about it as well when Tony [Kushner] asked me to play the part in Angels in America. My gut response was yes, this is a part that I feel strangely close to, even though I’m not gay. My first instinct was that this play was exactly where I want to be and what I wanted to be creating and how I wanted to be involved in my art.”

“We’re at a very interesting time now where there needs to be better representation of LGBTQ actors in the arts, as well as disabled actors in the arts. Tony said, ‘As soon as people start playing themselves, it’s the death of fiction,’ and I thought that was a really good point. But there is so much work still to do in terms of representation.”

As our conversation turns toward the political, Garfield is clearly someone who feels the weight of current affairs, both here and in the US (he has dual citizenship). I wonder if part of his decision to play minority characters is his way of contributing to the politics of representation. Will Breathe, even though a historical film, spark debate about the way many disabled individuals in the UK are being treated by the current government, many of whom are facing brutal benefit and care cuts?

“We’re in a time right now where people aren’t being valued,” Garfield begins, concern etched on his face. “There’s only a very small group of people who are being valued for who they are, so obviously there’s tremendous change that needs to happen. I don’t know if this film is going to make all that change, but my hope is that it is part of the conversation towards keeping the universe, keeping the world spinning forward, keeping the world spinning towards community, towards empathy, towards valuing each individual soul.”

BALENCIAGA suit, shirt, and shoes. Groomer: Sonia Lee. Photographed at Casa Perfect by The Future Perfect.

When it comes to America, Garfield is clearly upset about the toxicity of the current political climate. It’s the day after the Las Vegas tragedy and Garfield is clearly stung. He explains to me that he rarely goes online (he is famously absent from social media platforms), but went online for the first time in weeks to read news about the event.

“It’s not that I haven’t thought about using social media. It’s a great tool for so many things and I think some people use it in a very beautiful way. But I just went online…and I’ve come away after reading things feeling like I’ve swallowed a bunch of toxic waste. The tragedy itself is one thing, but the response to the tragedy…” Garfield trails off, pausing, still visibly affected by what he’s read.

“It’s quite terrifying that people are capable of responding with such insensitivity to the loss of human life. It’s absolutely overwhelming.” Garfield takes a moment, shaking his head. The conversation moves to the more positive voices to emerge from the tragedy, where hope can perhaps be found.

“Did you see Jimmy Kimmel’s monologue?” he asks me. “It was so courageous, honest and present. It felt like a transmission through him, that he couldn’t hold it anymore. It really was one of those moments where you see someone speaking for all of us. It’s very rare to see that in the public eye. There’s so much separation and it didn’t feel like he was separated from any of us at that moment. It was very representative of the grief many of us felt.”

This human connection is noticeably important to Garfield, as he explains that one of the reasons he still works on stage as well as screen is because of theatre’s ability to connect to an audience emotively and directly. “I need it. I really need it,” he tells me. “It feels like much more of a level playing field between the audience and the performers. And there’s much more of a pure transmission that happens. There’s less of a celebrity agitation and distraction from the actual thing that’s being transmitted: the story.” Going back to his first theatre role in Kes, he tells me that is still one of his most favourite performances.

“Kes was a big one. Billy Casper and Ken’s film and in that theatre and in the round. It’s hard to beat that experience. It was one of the experiences I’ll always think about because it was very pure and before any nonsense. It doesn’t get any better or pure than that. I didn’t even know what I was doing: I still don’t but I have to pretend like I do,” he laughs. “Back then, I could just be like: ‘I don’t know!’”

The nonsense appears to allude to the superhero juggernaut that was The Amazing Spider-Man, and the media frenzy surrounding his well publicized break-up with actress Emma Stone. I mention the franchise and Garfield pulls an awkward, clenched smile before describing it laconically as “tricky.” I comment on how much happier he seems today in his choice of roles and he nods in agreement.

“I think so. I kinda wonder if that isn’t possible for every person though. We’re all meant to do something particular,” he says, his eyebrows knitted in thought. “Obviously, sometimes we have to things we don’t want to do, but I do wonder about calling, about purpose and about whether—if we listen closely enough—we all have something specific and unique to offer and to do.”

Garfield pauses for a moment in thought, and then reaches for his phone. “There’s this E. E. Cummings quote I was reading earlier today,” he tells me, as he searches for it. He apologizes—“Sorry, this is boring!”— before reading the quote aloud to me: “To be nobody but yourself in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you everybody else—means to fight the hardest battle any human being can fight.”

The quote is a profound one and he notices my emotional response to it, E. E. Cummings being a poet who holds a special significance for me. We discuss the quote in detail and what it means to both of us before reflecting on how art—be it film, music or poetry—can help us understand our place in the world, especially at difficult moments like those faced by Cavendish and his family, or in our own lives.

“I always come back to that quote,” Garfield tells me, touching his heart and looking visibly emotional. “That keeps on coming back to me, that sentiment and that idea and how strangely hard it is to be oneself. It feels like it is a lifelong pursuit to dig down and bring whatever is the true self—that mysterious thing of the true self—up to the surface, offering it and giving it because it wants to be given,” he says. “There are so many opportunities to run away from it. It’s so easy to say: ‘No, not safe, not safe, not safe—I’m going to be rejected or I’m going to fail or I’m going to be disliked or someone won’t understand.’ What I’ve discovered is that if people are not understanding you or you are failing, that often tends to be a good sign,” he says with a wry smile and a wisdom well beyond his 34 years.

In the space of just over a year, Garfield has taken on four hugely arduous roles, one of which culminated in his first Oscar nomination, for Hacksaw Ridge. A soldier persecuted for being a Conscientious Objector because he refused to carry a gun, a Jesuit priest travelling to Japan, an AIDS sufferer, and now of course disabled rights campaigner Robin Cavendish. I put it to him that many actors might take on one of these roles in a lifetime, but not all four—and certainly not in the space of a year.

“That’s so funny!” he smiles, laughing loudly and nodding in agreement. “It’s been pretty crazy. When you put it like that I mean, it’s an interesting perspective. I hadn’t really thought of it like that, that most people only do one of them in a lifetime. I’m definitely tired!” he laughs again. “It’s been remarkable to take part in these things. I feel very grateful that I got the opportunity but I really appreciate you putting it in that context because it makes me go ‘Oh, it’s okay to be tired!’ It’s been quite a lot of work.”

Modesty is also something characteristic of Garfield, as is an awareness of his privilege as an actor—something he seems flatly uncomfortable with at times. “Even though it’s just playing pretend, it’s an interesting conundrum,” he reflects. “The thing between my awareness that it’s just ‘Oh, you’re playing pretend for a living,’ and how much it drains you. It can drain you so much.”

Having just finished its run at The National last summer, Angels in America is a play performed in two parts, each a grueling three and a half hours in length. It’s not long until Garfield resumes the role of Prior Walter in the play again as it travels to Broadway early next year. I ask him about when he will rest. He looks at me with a wry, teeth-clenched smile before laughing some more. Not for a while, is the short answer.

“I was excited to do a lot of reflection actually after the end of the play. I had a nice week off which was really good and I reflected on the last couple of years but I think I need a couple more weeks to really dig into what this has all been about. But I’m so lucky. I have mates that don’t get any holiday throughout the year so it’s hard to not just be grateful.”

Garfield chats about the moments of rest he does get in between, seeing LCD Soundsystem two weeks ago with his friends in London, for instance, or not having any plans—just having time to reflect. It’s not long before talk moves to his next project, a film he has already finished.

“It’s called Under the Silver Lake which David Robert Mitchell wrote and directed.” We talk about the director’s previous work on It Follows. “This film is crazier,” he tells me. “It’s really interesting and I’m excited to see how people respond to that because it’s very odd.”

As tiring as all this work may be, he’s well aware that he’s in an enviable position for an actor. It’s a position he’s reached through hard work, tenacity, and a knack for bringing an emotional depth to roles that is often unmatched by his peers, yet he’s too self-effacing to admit that. When I ask if Breathe could be his chance to win the Oscar, an embarrassed smile reaches across his face despite the fact that many are tipping him for another nomination.

“All the roles that I’ve done have given me something. Over these last couple of years, I’ve felt very grateful to have done Silence and Hacksaw Ridge. It’s been a really profound experience. As for Angels in America… one of the most privileged experiences I’ve ever had is to play that part.”

The interview draws to a close and we chat some more about LCD Soundsystem, Arcade Fire and of course, poetry. As we walk to the hotel lobby, I wish him good luck for the premiere; it feels like I’m saying goodbye to an old friend and not the Oscar nominated film star I met just under an hour ago. I switch off my tape recorder and thank him. “Has it definitely got it?” he asks, ever the meticulous professional, taking one last glance at my tape recorder. It has.

Written by Elizabeth Aubrey.

Photographer: Eliot Lee Hazel at Probation Agency.

Stylist: Mui-Hai Chu.

Flaunt film by Isaac von Hallberg

Groomer: Sonia Lee using Sisley Paris at Exclusive Artists.

Styling Assistant: Britton Litow, Amanda Alvarez, and Alex Ceballos.

Location: Casa Perfect.