Wild Spring | A Conversation With Barry Yusufu

by Tess Gruenberg

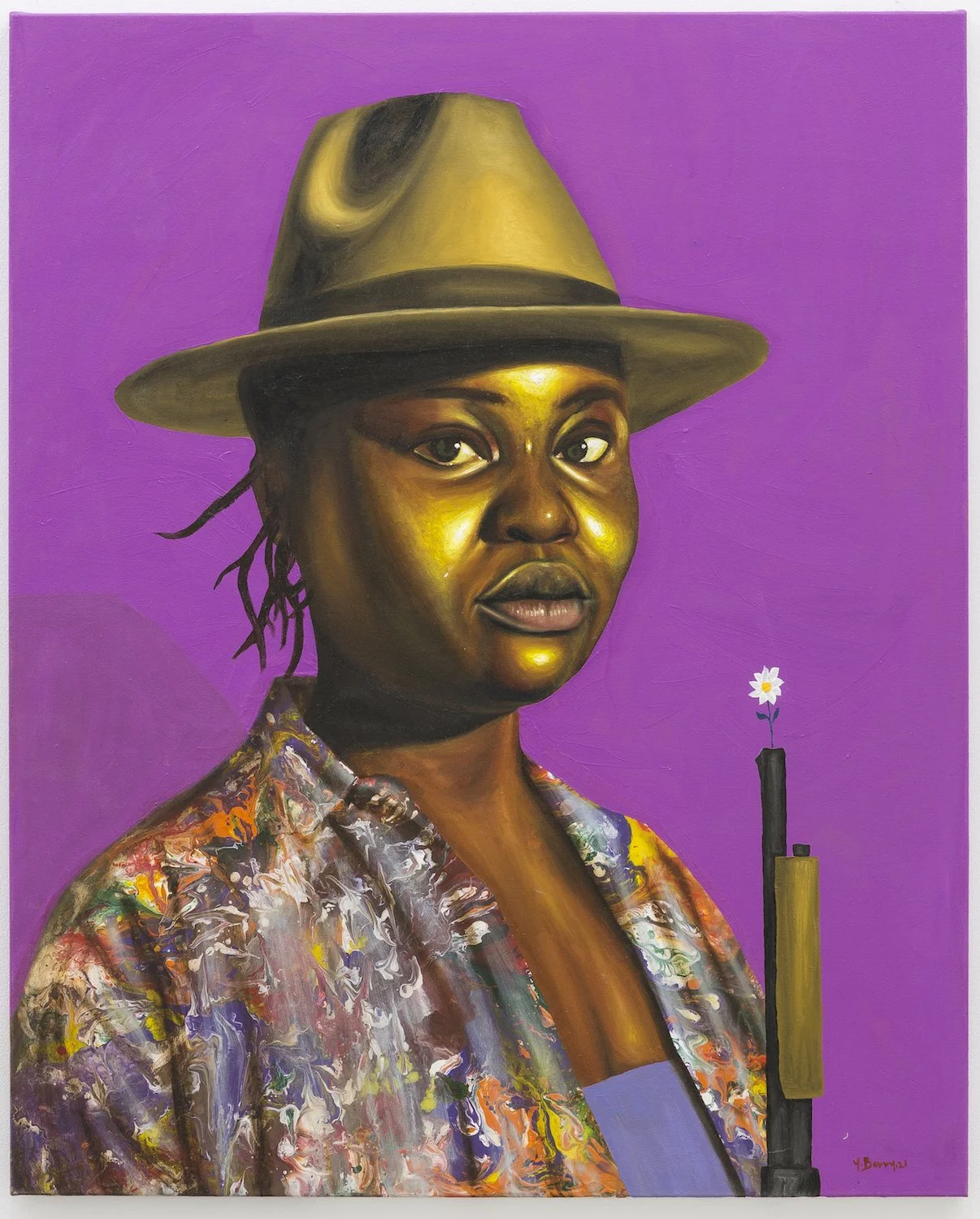

Barry Yusufu. “Bella Tubman” Courtesy of The Breeder Gallery.

It was an unusually warm April afternoon, and the streets of Athens emanated a sticky summer heat that called into question the fickle character of spring. I walked through the alleyways of Metaxourgeio to meet visual artist Barry Yusufu at his studio at The Breeder Gallery and thought the warmth symbolic. Because if Barry Yusufu was a season, he would be a wild spring day.

Barry sat stoically in front of his painting for the hour that we spoke. Mid-day sunrays streamed through the window and played in shadows on Barry’s form. Behind him was an African woman, her eyes soulful and teeming with stories. Her skin bronze, nearly neon in its strength. Soaked in layers of elements, she was painted in deep.

Photographed by Lida Macha. Courtesy of The Breeder Gallery.

As part of the open studio program of The Breeder Gallery, Barry had access to a studio across the street from the gallery for one month. The residency program gave him the space to complete a new series of paintings that will be exhibited at Art Basel this week.

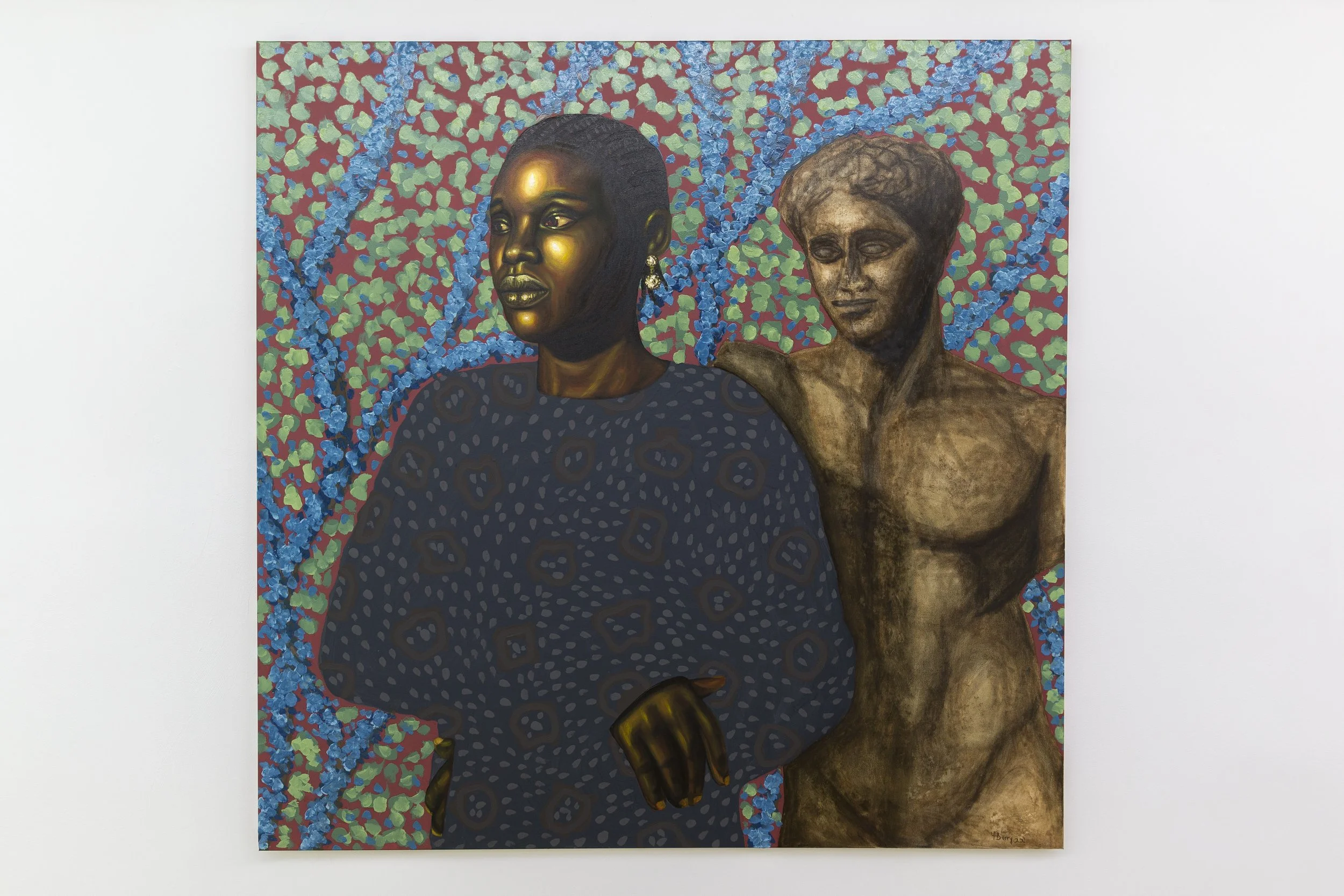

Flowers are everywhere in the five paintings leaned up against the walls of the studio. The series brings together two seemingly disparate themes: the people of Nigeria and Ancient Greece. The flowers that pepper his canvases feel word-like, as though they articulate the existence of a shared language. “When I paint, it's like I'm sculpting on a canvas,” Barry said. “I want to mix the old and the new, mix this side of the world and my side of the world in one place, where it doesn't look like they are contradicting each other. They can sit perfectly in the same place, in the same room.” I eyed the Acropolis looming over a pasture and asked him about his time in Athens. “I've loved being here. You are closer to the sky in Athens,” he said. “But there isn't enough spice here. Always asking for salt.”

This wasn’t the first meeting for the two of us. Only days before I spent hours deep in conversation with him and my partner on the terrace of our apartment in Monastiraki. Barry’s catapult into the art world, I told him that night, was like a dream. Cinematic at its essence, a backdrop ripe for fantasy.

Barry Yusufu. “Abigail and Kyniskos” (2022). Acrylic and oil on canvas. 150 x 150 cm. Courtesy of The Breeder Gallery.

Born and raised in Nigeria, Barry only began to draw a few years ago at the green age of twenty-four. “I didn't go to an art school. I didn't study art anywhere. I picked it up myself. I started with pencils. Just pencil. And to start achieving depth and darker shadows in my work, I graduated to using charcoal. Charcoal was a very comfortable material to paint Black figures.” There were more graduations in store.

Once his drawings started to sell, Barry started experimenting with a more symbolic material of African history: coffee. He poured coffee onto a canvas lying flat on the ground. He spoke to himself and watched as the raw material of the charcoal soaked the coffee up and then transformed into a texture that surprised him. The details were smooth yet sharp. “This is it,” he said to himself that day, “I found something that was special.” Harnessing the subtleties of mixing charcoal and coffee, Barry painted a series of portraits that juxtaposed objects of culture with the subject of African people. He played with the aperture of the paintings. The object—a television, flower, a piece of clothing—would sit in focus. The person, blended with charcoal, would be positioned stoically in the background.

The art market ate it up. Devoured the coffee, loved the charcoal. “In a way that's what people wanted to be able to see.” Barry said. “By using coffee and charcoal I was able to show how my people were being placed in the background. I was reflecting that attitude in the African being. How colonialism affected us. How we were being sold for objects. They wanted to see that sad story. They want to see that pain.”

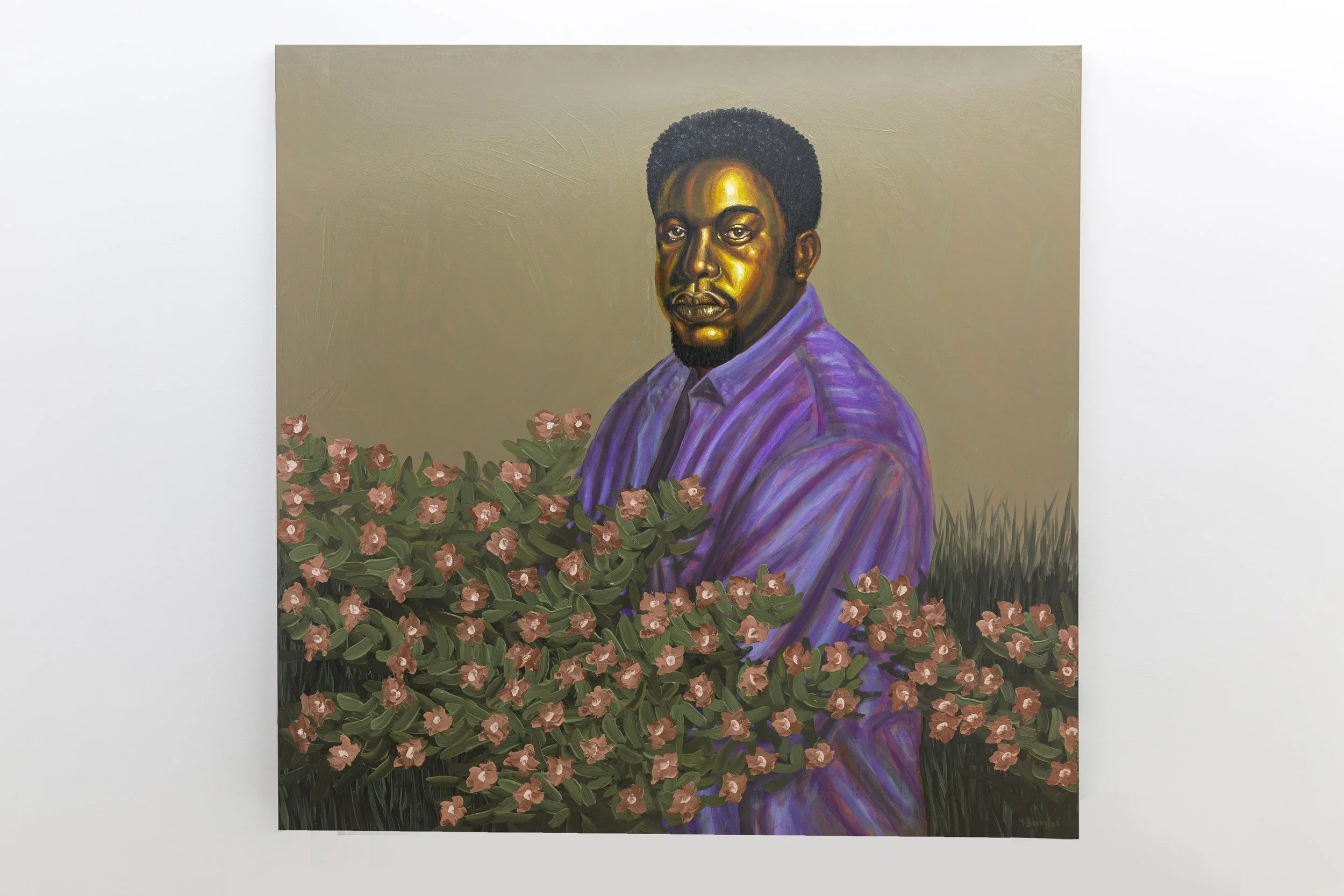

Barry Yusufu. “Uncle Obie” (2022). Oil on canvas. 150 x 150 cm. Courtesy of The Breeder Gallery.

Unfazed by the success, Barry decided to pivot. Months before a January 2022 solo show in Italy, he worked tirelessly to bring a new element into his arsenal: bronze. And when gallerists asked him to show his work for the show—expecting the sold-out series of charcoal and coffee—he presented a completely novel collection of art featuring Black faces painted bronze. “The system was telling me to paint the same sad story because that's what the market wanted. The pain was easily marketed. But I said nah. It's time to take my people out from the background and into the focus.”

His choice to paint with bronze is a continuation of his resolve not to be pigeonholed or classified as this or that, actively subverting the difficult loop many young artists find themselves in—‘marketable’ being a spectre of a word that haunts both artist and gallerists alike. “Many of the curators said the works wouldn't sell. I said, show the work and if they don't sell, send my works back to me,” Barry told me slyly, a laugh beneath his breath. “All the works sold before the show started.”

Bronze reigns supreme in these five paintings he sculpted during his time in Athens. And that’s by design. “I pity whoever doesn’t think they are god. That's the first step,” Barry said, “I want to paint where my people are headed. A different level of glory.” He arranged himself like the woman he painted, sitting tall. Pain is there, love even more so. “The African people,” he said emphatically. “We share the same story. If I am painting their story, I am painting my story.”

Barry Yusufu. “Enoch X” Courtesy of The Breeder Gallery.

Representation is a question that looms over the conversation between us. As a writer I am weary of describing Barry as an African artist, fearing the colonial classification that he fights against daily. “A lot of people think it stops at representation, and that's where it starts. It is not representation. Anybody can represent anybody,” he said as he looked up at his own work. His face suddenly appeared bronze. “It is about proper representation.”

As I spoke to Barry, I decided that I was right. He is a person of spring. He evolves on his own terms and stubbornly shrugs off the expectations thrown at him as an artist. “When you look at my works, you're going to see that there is an infinite process. There is never a place in time.” It’s the tragedy of a flower. The language of his art is vibrant and paradoxical, all bathed in wild color.

“I feel what makes a painting complete is the reference to the past, present, and the future,” he said and smiled, “and a little bit of a dream.”